The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Circus

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Circus

[media]In hindsight, it seems strange that circus took such a long time to gain a foothold in Sydney, Australia's first settlement and oldest city. From the arrival of the First Fleet, more than 60 years had to pass before Sydney was served by its first circus establishment, the Royal Australian Equestrian Circus, opened in York Street in 1850. From that point, however, Sydney's penchant for circus continued unabated. Despite wars and depressions, the rise of alternative forms of popular live entertainment such as vaudeville and variety, and the introduction of cinema, television and the more recent forms of electronic media, the record shows that Sydney enjoys a good circus. In 1997, Sydney's Powerhouse Museum went so far as to present Circus!, an exhibition of antique circus memorabilia, to mark the 150th anniversary of circus in Australia. [1]

The modern circus crystallised in London from 1768. Riders used to give open-air displays of trick horsemanship in a field called Ha'penny Hatch at Lambeth on the Southside of the Thames, London's southern outskirts at the time. Some of these displays began to assume the form we associate today with circus. Crucial to these developments was a former cavalryman and veteran of the Seven Years War, Sergeant-Major Philip Astley. Astley (1742–1814) combined displays of horsemanship with acts by clowns, ropewalkers, tumblers and gymnasts. By 1779, he had enclosed these displays within a permanent venue, near the south side of Westminster Bridge, which he named Astley's Amphitheatre. This new genre of entertainment was popularly known around London as 'the circus' and the name stuck, although Astley himself never used the word to describe his amphitheatre. In the vernacular of eighteenth-century London, the word 'circus' described the large, open-air, circular riding tracks used by recreational riders, traces of which remain today in thoroughfares such as Piccadilly Circus. Although the circus of modern times, beginning with Astley's, and the circus of ancient Rome share some features, the evolutionary link between the two is, at best, tenuous. [2]

Destroyed by fire and rebuilt several times, Astley's Amphitheatre remained a major international focal point for circus activities long after its founder's death. The establishment reached the peak of its fame in the years 1825–41 under the management of the superlative horseman, Andrew Ducrow (1798–1842). Ducrow raised the spectacle of circus riding to an art form. His exquisite equestrian-based pantomimes and spectacles were imitated in circuses throughout the British Isles, on the Continent, in the new United States and in the new colonies of Australia.

Since Elizabethan times, the travelling entertainers of England's fairgrounds, such as ropewalkers and acrobats, carried the legal status of 'rogues, vagabonds and sturdy beggars' in the English social hierarchy. [3] From their ranks were drawn the first generations of circus performers in late eighteenth-century England and their pre-existing social standing accompanied them. [4] Circus performers invariably came from underprivileged backgrounds. [5] Some of England's circus performers, falling foul of law, found themselves transported to Australia. Their enforced relocation contributed to the foundation of an Australian circus industry.

Early circus activity in Sydney

The modern circus was still a new genre of entertainment when the First Fleet sailed in 1788, but many of the fleet's human cargo had probably witnessed, or were at least aware of, the delights of Astley's. However, organised popular entertainments were not among the priorities of a penal settlement. Sydney was not served by regular theatre performances until the 1830s and then only with difficulty.

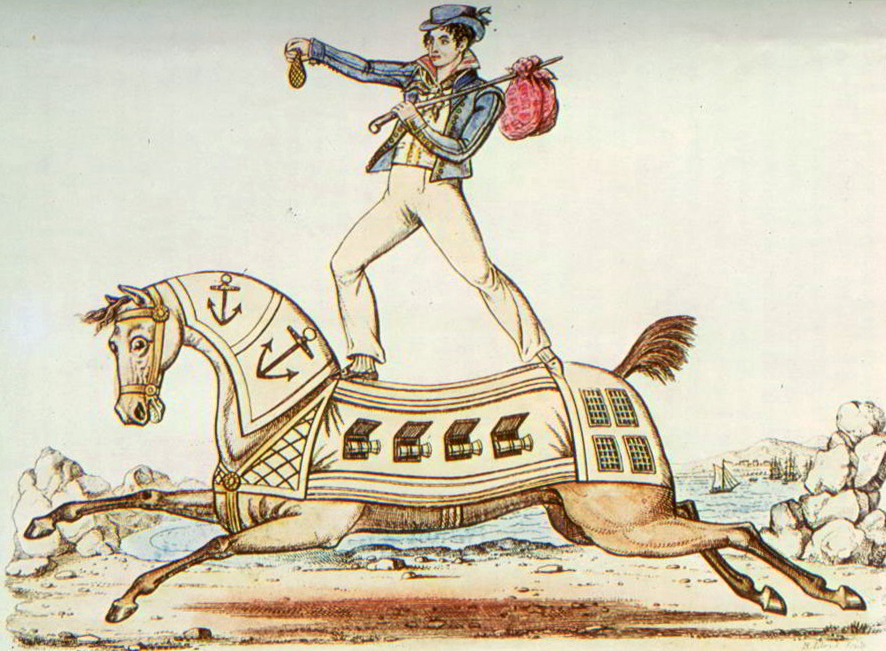

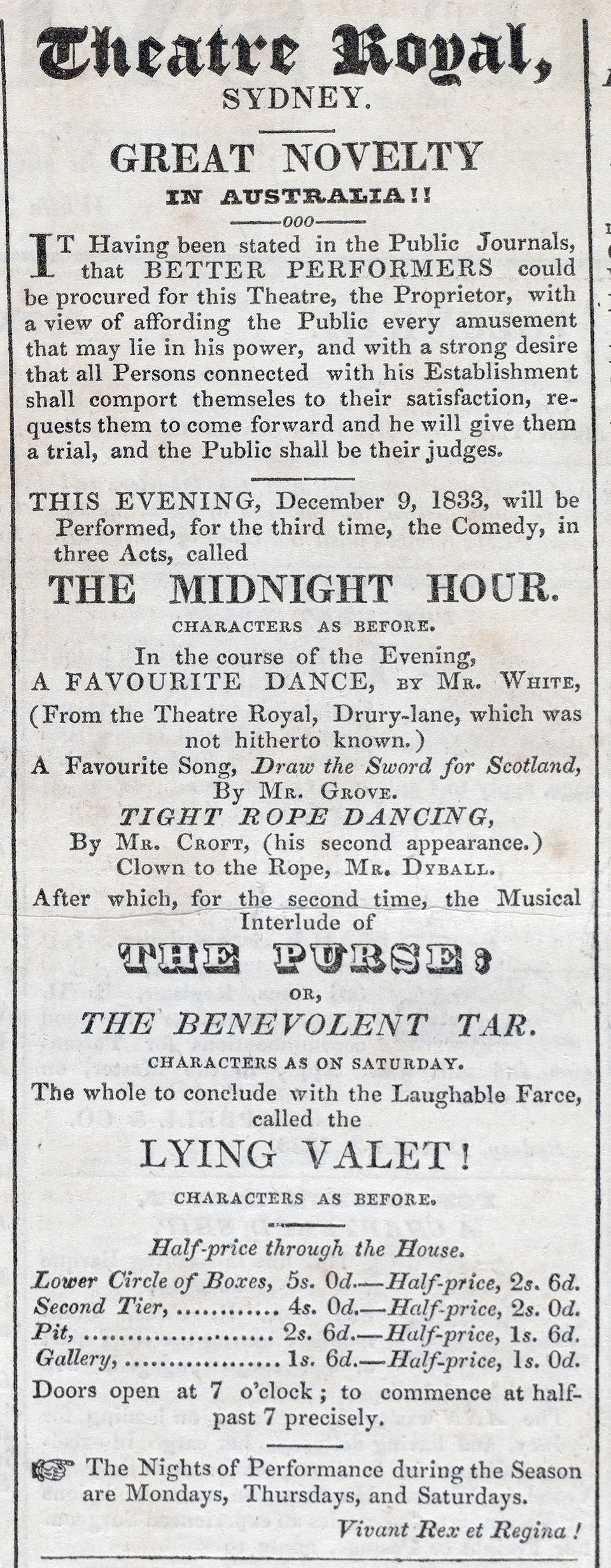

[media]As early as 1833, entertainments of a circus nature were given in Sydney when two ropewalkers, one a former convict, gave performances on the stage of the new Theatre Royal. [6] During the 1830s and 40s, the range of entertainments in Sydney gradually expanded to cater for growing numbers of 'plebeians', whether emancipated convicts and their progeny or the steadily growing number of free settlers. This was 'popular' entertainment, entertainment for its own sake rather than for the purpose of communicating the moral values of the 'respectable and fashionable' of the colony's 'upper orders'. [7] Nevertheless, a remote penal colony held little promise and visiting artists, popular or otherwise, from London or the Continent were few before the gold-rush period of the 1850s.

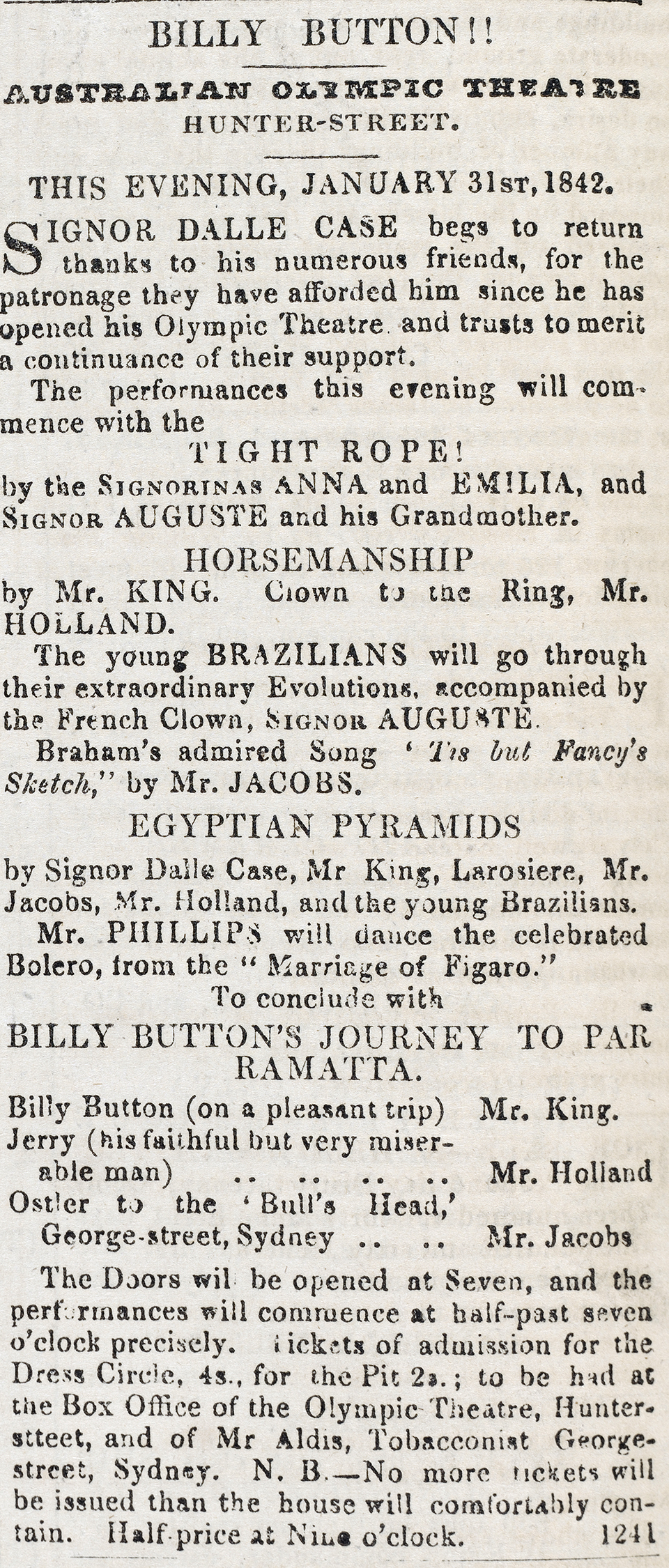

[media]A self-styled 'Professor of Gymnastics', the (apparently) Italian Signor Luigi Dalle Case, and his little troupe serendipitously arrived in Sydney in July 1841, in the midst of an economic depression. [8] Dalle Case had come by way of Bahia, Buenos Aires, Cape Town and Mauritius and, during a stay of several months, enlivened Sydney's moribund theatrical scene. Early in 1842, he opened a short-lived, circus-style pavilion in Hunter Street, named the Australian Olympic Theatre, and gave Sydney its first comprehensive circus performance, replete with equestrians, ropewalkers, gymnasts, acrobats and clowns. [9] Awakened from their slumber, Sydney's own theatrical entrepreneurs were stirred into action and were soon raising their own production standards. Bankrupted within a few weeks by the competition he had stirred, Dalle Case moved on to give entertainments in Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania) before departing, enriched once again, for India. [10]

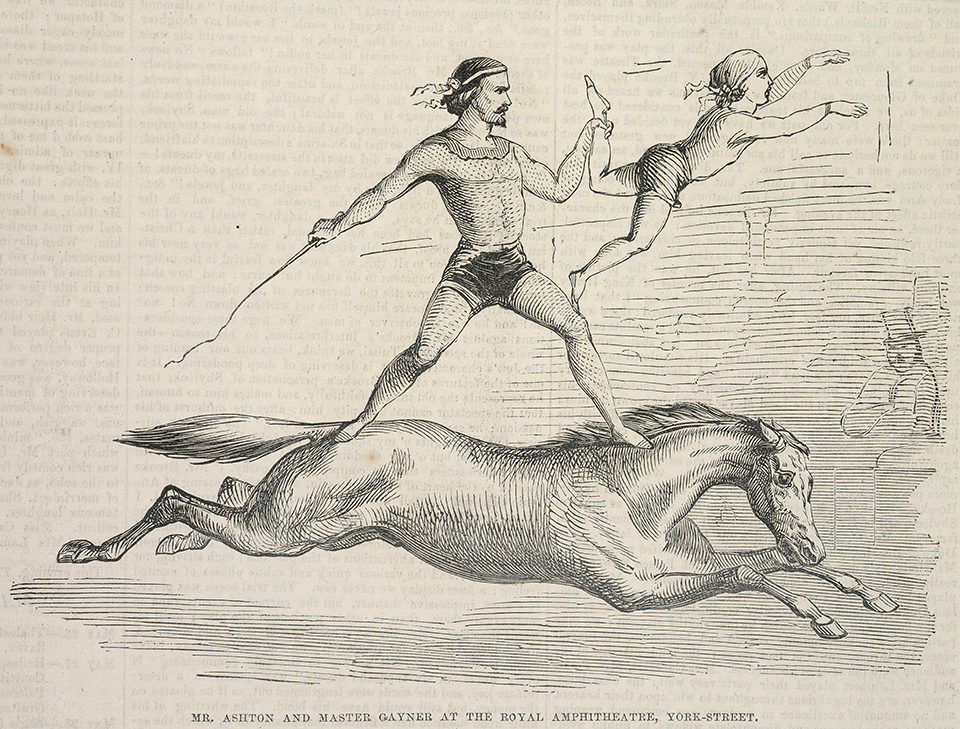

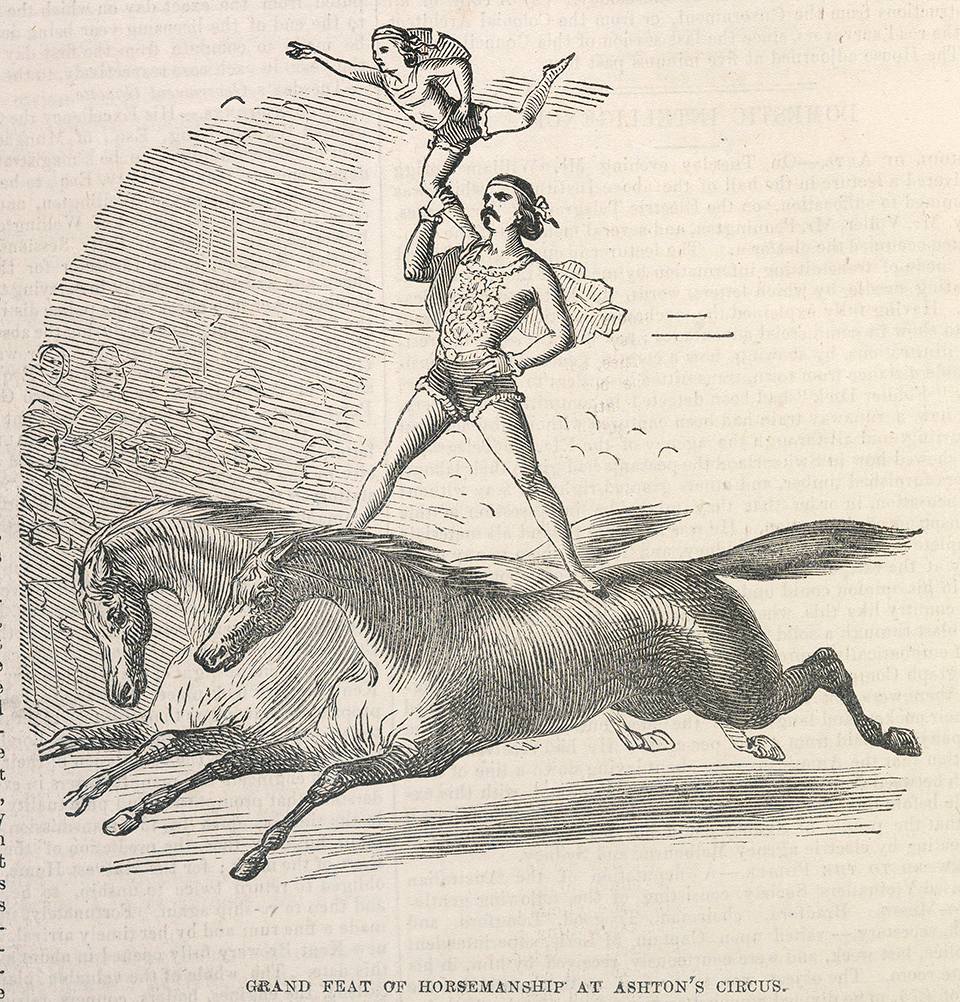

Although Sydney was the location of Australia's first signs of circus activity, the first major developments took place in Van Diemen's Land. In Launceston, in December 1847, a publican and professional equestrian named Robert Avis Radford (1814–65) opened Radford's Royal Circus at the rear of his Horse & Jockey Inn. [11] After some two years of almost continuous circus activity, the enterprise eventually left Radford insolvent. But the development of a colonial circus industry had been set in motion. [media]Two of his equestrians, Golding Ashton (1820–89) and John Jones (c1826–1903), eventually established colonial circus dynasties in the tenting tradition, under the professional names (' noms d'arena') of 'James Henry' Ashton and 'Matthew St Leon' respectively. As a result of their efforts, the history of almost any Australian circus of note, including several in existence today, can be traced, directly or indirectly, to Radford's pioneering circus enterprise. [12]

From equestrian troupe to Hippodrome

In the winter of 1849, after participating in a short-lived circus venture in Melbourne, Ashton and his little equestrian troupe travelled overland from Port Phillip along a track that meandered from one waterhole to another to reach Sydney. [media]According to Ashton family legend, they gave al fresco equestrian exhibitions in a makeshift ring near the site of the present-day Central Station. [13]

A few months later, John Jones and his equestrian troupe arrived from Hobart Town after an Irish-born ropewalker, Edward Hughes (c1824–57), professionally known as Edward La Rosiere, engaged their services at a weekly salary and paid their passage to Sydney. [14] Opening in the City Theatre – somewhere opposite the present-day State Theatre – in Market Street in January 1850, this 'unprecedented novelty' embraced gymnastic feats, tightrope, slackrope, vaulting, acrobatic and equestrian feats. [15] In the following months, Jones, La Rosiere and the troupe gave open-air performances in and around Sydney and toured outlying townships as far as the Hunter Valley. Returning to Sydney, Jones and La Rosiere organised and opened the Royal Australian Equestrian Circus in October 1850. The circus was conducted within a roofless arena erected in the backyard of John Malcom's Adelphi Hotel in York Street, between Market and King Streets. Many years later, the locality was described as a neighbourhood that was, at the time, 'not of the sweetest'. [16] To accommodate the arena, Malcom had to make alterations and extensions 'at great expense' to the rear of his hotel. The circus opened in October 1850. [17] The establishment was licensed for horsemanship, tumbling and rope dancing, initially for three-month periods. The Colonial Secretary, E Deas Thomson, imposed a firm condition: no convict,

whether serving under any temporary remission of Sentence or otherwise, [was to] to act, perform or appear in said Circus. [18]

The doors of the Royal Australian Equestrian Circus opened three evenings a week, precisely at eight o'clock. There were prices of one, two and three shillings to the pit, gallery and boxes respectively, with half prices for children under the age of 12. To convey families home after the performance, carriages waited outside the hotel. As Christmas 1850 approached, new acts of horsemanship, acrobatic skills and other novelties were introduced into the program, especially after the fortuitous arrival of English circus man Henry Burton (1823–1900) and his wife, the renowned equestrienne, Madam Rosina (c1824–1860). [19] Although the short skirts, tights and pirouettes were somewhat vulgar by the moral standards of the day, they added a touch of spice to the entertainment. [20] Realising the commercial potential of the enterprise lying in his own backyard, landlord Malcom soon usurped his tenants and renamed the enterprise Malcom's Royal Australian Circus. It was thereafter known around Sydney as 'Malcom's' and Malcom continued to develop the venue over the next few years. On occasion, Malcom took the troupe on brief excursions to the Homebush races, the pleasure grounds at Botany Bay, and the outlying township of Parramatta. [21] The 'renowned British horseman', Ashton, had already caused a stir when he made his first appearance in Malcom's in Sydney in August 1851. [22]

A circus performance of this era, as seen in Malcom's, differed considerably from the eclectic representations of 'circus' that are offered to audiences today. The early colonial circus productions owed much to Astley's Amphitheatre in London and the pantomimes and spectacles of its principal equestrian, Andrew Ducrow. The only living creatures seen in the circus ring were men, women and horses. There were no wild animals. The ring performance was dominated by feats of bareback equestrianism, ropewalking, tumbling, acrobatics and gymnastics. Clowns dressed each performance with their presence and antics. There were no trapeze acts at this stage as the invention of this performance medium and its introduction to the colonies was still a decade away. Equestrian acts comprised not only energetic displays of 'trick' riding and posing on horseback but artful and elaborately costumed equestrian pantomimes in which stories of shipwrecked sailors, Roman gladiators and Swiss milkmaids were played out on horseback. A 'band', possibly no more than a violin, tin whistle and bass drum, accompanied the performance. Everything was overseen by a maitre du cirque, or ringmaster. A long stage ran adjacent and overlooked the circus ring upon which short theatrical interludes and pantomimes were presented. Each evening's performance was brought to a close with an 'extravaganza' or 'laughable afterpiece' such as Jack and the Beanstalk. These short plays were designed to send the audience home in a happy mood and the equestrians and others who had appeared in the ring transformed themselves into actors to act out the parts required.

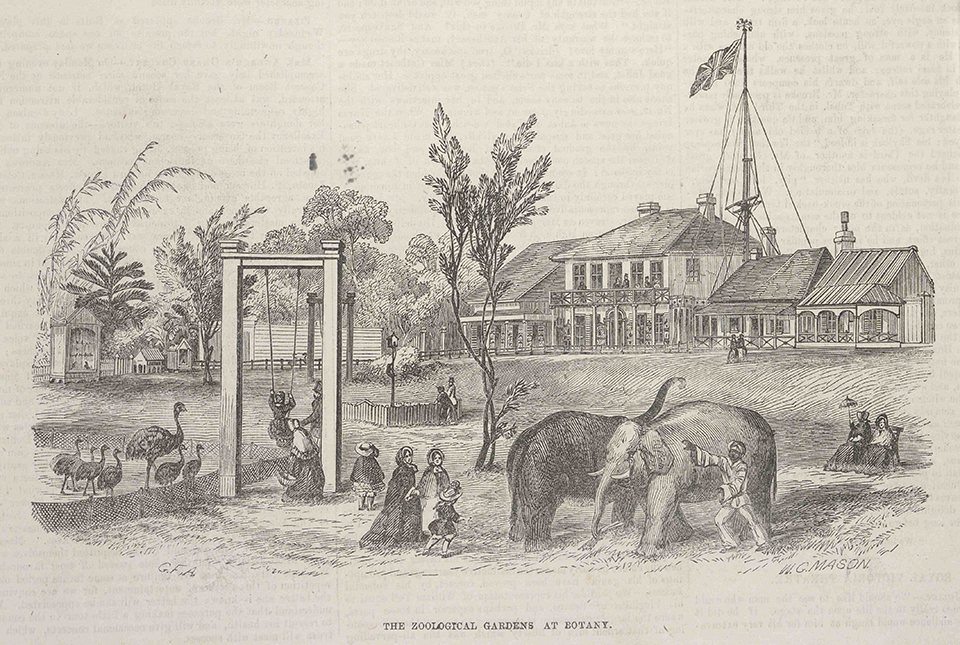

In the late 1840s, the Sir Joseph Banks Hotel opened on the north shore of Botany Bay. [media]To attract Sydney's pleasure-seekers on weekends and public holidays, William Beaumont and James Waller opened a pleasure garden and open-air amphitheatre adjacent to the hotel. Malcom's ringmaster, Henry Burton, spent six weeks breaking in riders and horses. Two thousand people witnessed the inaugural performance at Botany Bay on Boxing Day, 1850. Some spectators came by the large, heavy coaches that ran along the crude road that stretched from the city to Botany Bay. Others came by the Sir John Harvey, 'the most magnificent steamer in Port Jackson', which carried its own bar and a quadrille band to relieve the tedium of the voyage. Visitors to Botany Bay could also visit Beaumont and Waller's zoological and botanical gardens where they could see wild and exotic animals. [23] At various times, the collection of animals included an elephant, a royal Bengal tiger, a Himalayan black bear and other species of bears, and wolves, many of them novelties to the 'currency' lads and lasses who had grown up in the colony. [24] Many of the non-indigenous animals were procured and landed in Sydney by mariners, Captain Charlesworth of the Royal Saxon being especially active in this regard. [25] In June 1851, for example, the Royal Saxon arrived from Calcutta carrying a young elephant Charlesworth had procured for Beaumont and Waller. [26] Although the wild and exotic animals displayed at Botany Bay were not part of the circus performance presented by Malcom's troupe, their presence was nevertheless prophetic. Later in the century, itinerant Australian circus proprietors borrowed the American idea of attaching menageries of 'wild beasts' to their travelling companies. From these sideshows, some animals – such as lions, tigers and elephants – were eventually integrated into the circus performance.

As increasing numbers of Sydney folk were entertained in Malcom's Royal Australian Circus in York Street, its seating capacity was tested and Malcom had to periodically reconfigure the venue. In August 1851, for example, he 'considerably enlarged and roofed' the building, and expanded the pit to accommodate 1,000 people by eliminating a gallery at the rear. [27]

Malcom offered apprenticeships to youths and young girls. His most outstanding apprentice was a lad from North Sydney, James Munro (1837–92), the son of Scottish immigrants, who appeared under the nom d'arena of 'James Melville'. Melville's daredevil equestrianism consisted of 'a series of wildly beautiful pictures, which once seen can never be forgotten'. In 1857, Melville, his family and troupe sailed for Valparaiso before proceeding to San Francisco to find fame and fortune. By 1861, Melville was travelling the United States with his own company, Melville's Australian Circus. During the Civil War, his 'Australian' status assured him and his company of a degree of neutrality in the conflict and they were able to freely move

along the Mississippi River in a sternwheel steamboat, landing and giving performances, often to Union soldiers one day and Confederates the next. [28]

Visiting Sydney in 1852, the English writer John Askew noted:

two circuses [Malcom's in York Street and the Olympic in Castlereagh Street] in each of which pantomimes are performed as well as astonishing feats of equestrianism. There is also a menagerie in Elizabeth Street that contains an elephant, two or three monkeys, a lion and a lioness and a few other animals of the cat species. In summer time, these animals are kept in a wooden building in the street and on the setting in of the rainy season they are removed to Botany Bay. The prices of admission to these places are from one shilling to three shillings and sixpence. [29]

For Easter Monday, 1852, Beaumont and Waller engaged Ashton and his partner, 'Signor' Cardoza, to present a 'Grand Equestrian Exhibition' at Botany Bay. [30] Ashton announced he would ride four 'splendidly caparisoned' horses from the Botany Road toll-bar to the gates of the Sir Joseph Banks Hotel on the day, a distance of about eight kilometres, in 30 minutes. He wagered 'any respectable person' £50 to £100 that he would perform the feat in 20 minutes. [31] Thousands lined the route in anticipation but the earthen road was so muddied by recent rains that the affair was aborted. [32] At Botany Bay later in the day, some 7,000 people watched Cardoza walk down a tightrope, slanted from the top of an old tree to a windlass below. [33] Throughout the day, the City Band serenaded the crowds with polkas, waltzes and quadrilles. Ashton gave equestrian performances at half-hour intervals in a large canvas tent. [34]

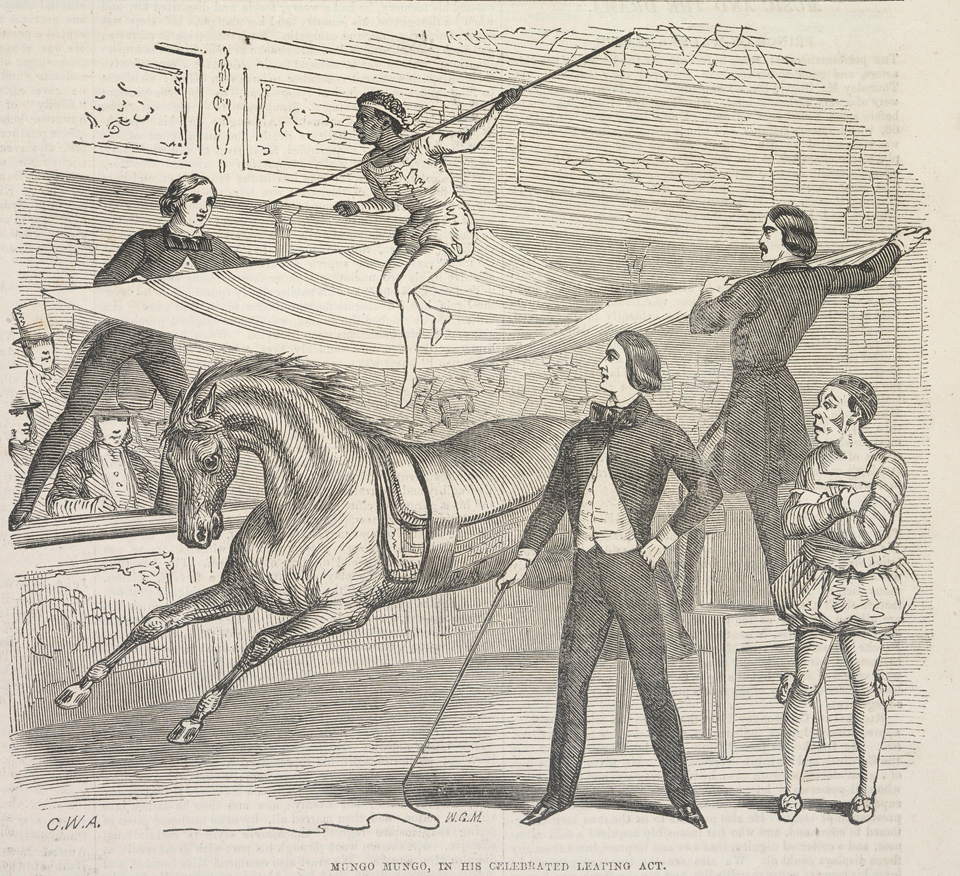

Malcom's installation, in July 1852, of a stage adjacent to the original circus ring transformed the Royal Australian Circus into a genuine 'amphitheatre' and it was now renamed Malcom's Royal Amphitheatre. [35] In October 1854, as Sydney audiences began to tire of equestrian performances, Malcom transformed the building into a conventional theatre, and renamed it the Royal Lyceum. [36] The move was not successful. The building was returned to its original equestrian purpose when Ashton and his troupe played a five-month season from May 1855. Despite the numerous competing attractions, including the infamous danseuse Lola Montez (1818–61), Ashton was enthusiastically patronised by the Sydney public. [37] During the season, Ashton introduced the novelty of a young Aboriginal equestrian he had trained, Mongo Mongo, who came from the Tamworth area. [38]

The gold rushes of the 1850s not only attracted large numbers of fortune-seekers to the colonies, but created audiences that were larger, more affluent and cosmopolitan, and demanded a diversity of entertainment, not just amphitheatres and circuses. The need for permanent circus establishments in Sydney receded as audiences tastes changed in favour of theatre, music and variety. The Olympic Circus was refurbished and reopened as the Royal Marionette Theatre and was later rebuilt as the Royal Albert Theatre. [39] Converted once again into a conventional theatre after Ashton's season, Malcom's edifice remained in use until 1882. By then known as the Queen's Theatre, it was condemned as unsafe and demolished. [40]

In ancient Rome, chariot and horse races and spectacular exhibitions of bareback riding were held in long, oval-shaped, open-air arenae such as the Circus Maximus. Almost 2,000 years later, the French circus man Henri Franconi revived these ancient spectacles in a modern form and, in 1853, entertained New York with his 'hippodrome'. [41]

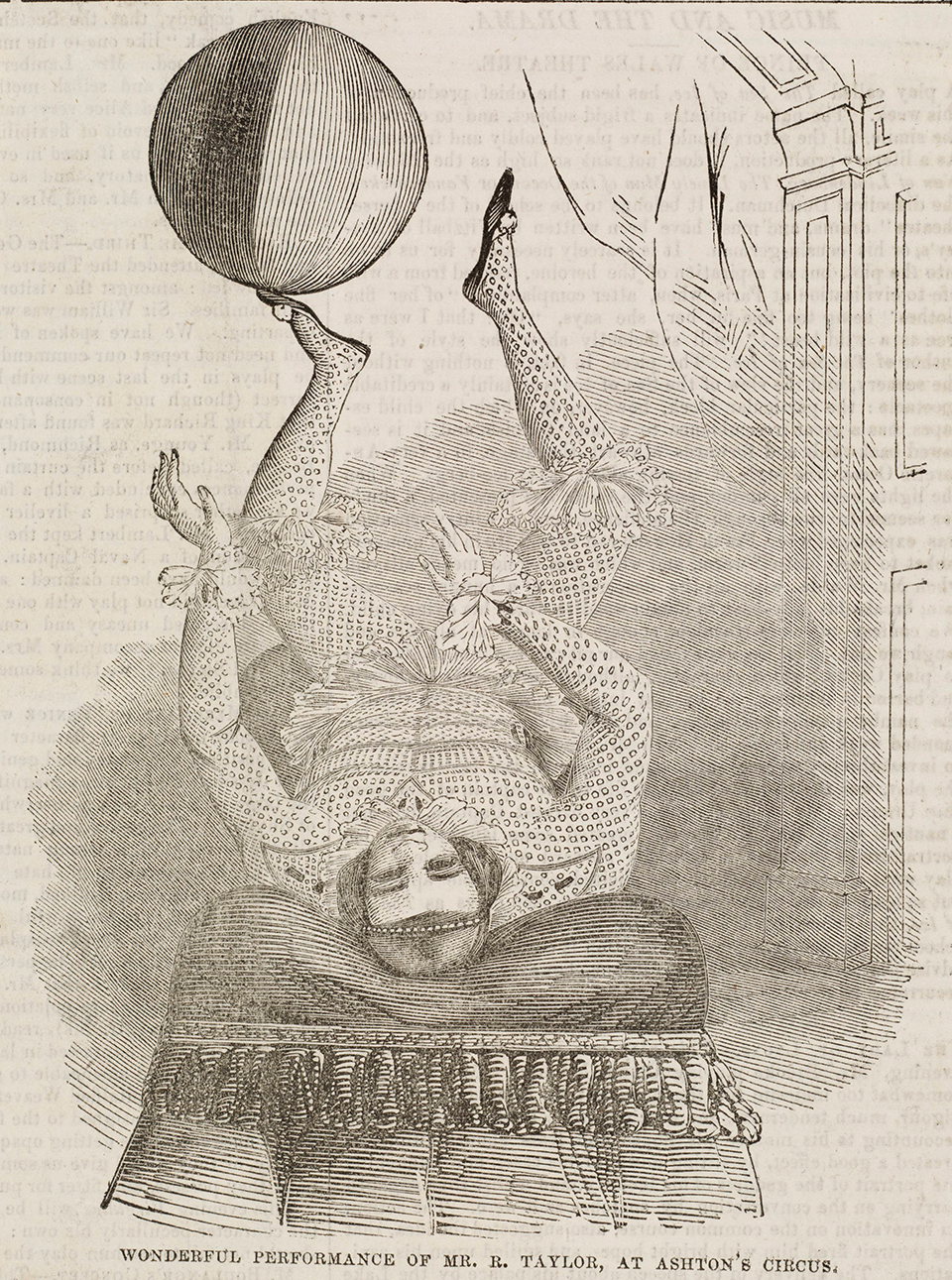

The word 'hippodrome' was used in colonial circus advertising as early as 1855 when James Melville took his circus to Moreton Bay. However, the first genuine 'hippodrome' in an Australian setting may have been presented by Thomas Bird (1837–77) and Robert Taylor (1833–1918) in Sydney on the Queen's Birthday, 24 May 1871. [42] The affair attracted some 6,000 spectators and consisted of a large open-air fete, complete with a fun-fair, open-air circus performances, and chariot races, acts of horsemanship, and Roman races along a quarter-mile course. [43] Bird and Taylor were well-known colonial circus identities. Bird, a former apprentice of Malcom, was nicknamed 'gunner' because of the patch he wore over one eye. He was renowned for his artistic 'posture' riding. [44] Taylor, [media]who had been an apprentice of Ashton, was renowned for his skilful balancing and juggling on a rolling globe. [45]

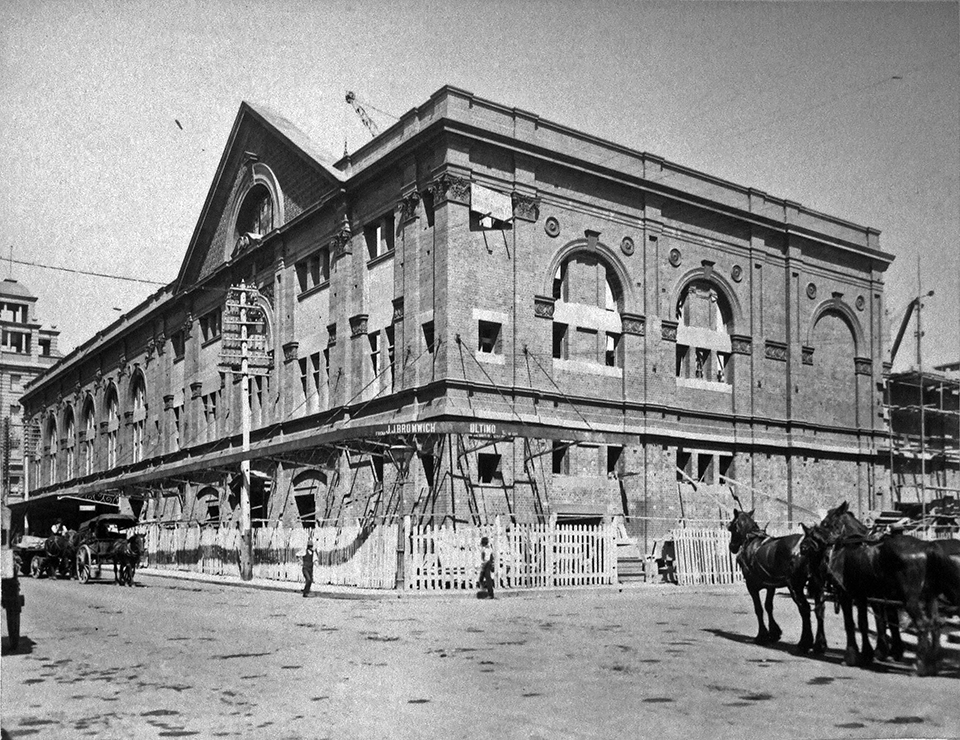

In the post-gold rush era, periodic visits by touring circus companies – perhaps only two or three a year – were sufficient to satisfy Sydney's demand for this 'class' of entertainment. No permanent, purpose-built circus building was used in Sydney again until [media]the Sydney City Council erected a 3,000-seat multi-purpose venue in the Haymarket in 1913–16 at a cost of £32,500. Although this massive edifice bore little resemblance to the hippodromes of either Franconi or of Bird and Taylor, it was nevertheless named 'The Hippodrome' in the flavour of the times and was built

on the same scale of magnificence as the Great Hippodromes of London and New York for the production of all classes of entertainment.

The Hippodrome featured a vast auditorium with a perfect view of the arena and stage from every part of the house. Wide marble staircases led to a dress circle that stretched around the house to link up at each end with the proscenium that framed a spacious stage. The ring featured a movable floor which could be lowered to a depth of 2.4 metres so that it could be flooded within a few minutes with more than 900,000 litres of water for presenting aquatic displays. Beneath the stage and arena were large pits where the animals, including elephants, waited before their performance. Acts could take place alternately upon the stage or in the ring so that performances could proceed without interruption. On completion, the Hippodrome was leased to Wirth's Circus Ltd just in time for its annual Easter season, opening on 3 April 1916. [46] At the conclusion of Wirth's inaugural season, the Hippodrome was reconfigured for Wirth's production of the imported English wartime propaganda play, Kultur, by Leonard Durell. This realistic but expensive production presented scenes with horse-drawn cannons, with gunners, postilions and full artillery equipment. Despite the patriotic furore the production had created in England, Kultur was a 'flop' in Australia. George Wirth recalled:

Australia, or rather Sydney, was too far away from the war, and the propaganda was not required to stir the loyalty of the nation as it was in England. [47]

Despite the Hippodrome's admirable features, the colossal edifice ultimately proved uneconomic for either circus or theatre. With the growing popularity of the 'movies', it was leased to Union Theatres Ltd in 1928, refurbished and reopened as a cinema, and renamed the Capitol Theatre. In 1993, the building was again refurbished and reopened as Sydney's only lyric theatre, but the name of 'Capitol Theatre' was retained.

Gold and the touring circus

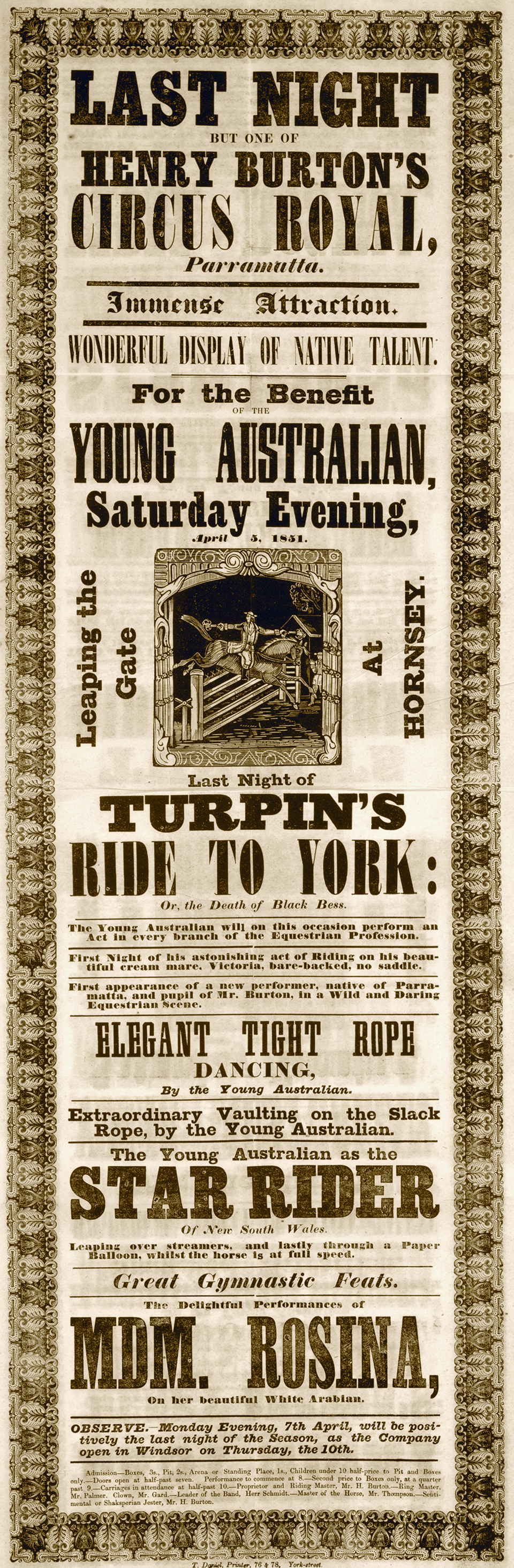

The early colonial circus men found, as had the wandering minstrels of mediaeval Europe and the circus men of the American frontier, that it was easier and more economical to change audience than repertoire. To change audience however, they had to change location. [48] [media]Late in February 1851, Henry Burton left Malcom and, organising a travelling company in the provincial English style, opened his Olympic Circus and Modern Arena of Arts in a pavilion at Parramatta, on ground adjoining Curran's Glasgow Arms. [49] After a short season there, Burton moved overland to Maitland but was soon deprived of audiences with the announcement that gold had been discovered near Bathurst. Recognising a fresh opportunity, Burton and his troupe made the journey to the diggings with packhorses by way of Mudgee. After more than a year on the goldfields, they returned to Sydney, thereby completing the first major touring circuit by a travelling circus in Australia. Early in 1853, Burton and his company headed for the new goldfields of Victoria. [50]

Initially, Burton's and other early peripatetic circus troupes relied on transportable but cumbersome pavilions, semi-permanent structures of timber and canvas similar to the 'booths' used by showmen on the English fairgrounds. These had to be erected and dismantled at each location. But, as circus proprietors on the American frontier had found in the 1820s, tents were cheaper, lighter and more easily transported, raised and lowered. [51] Given the distances to be covered and the absence of formed roads, bridges and purpose-built venues, tents also suited Australian conditions. By the summer of 1853–54, there is clear evidence of the regular use of canvas tents by colonial circus proprietors. [52] As a result, circus troupes began to service the numerous regional towns which emerged with interior settlement, agricultural and pastoral expansion and the prosperity generated in post-gold rush Australia. The social, economic and cultural importance of the horse assured any circus of merit of an audience. [53]

Most of the early Australian circuses were built on the basis of the family, skills and experience being accumulated and transferred to each new generation. The family-based circus tended to seek the freedom, informality and quietness of the bush rather than the noise and bustle of the cities and suburbs. With their irrepressible tenacity to travel and entertain, the more capable (and fecund) circus families – such as the Ashtons, Perrys and St Leons – survived the economic tides to build dynasties and reputations that lasted a century and more. Today, [media]after some 160 years of activity, the seventh-generation Ashton progeny conduct Ashton's Circus, the oldest circus travelling Australia – if not the world.

From the time he departed Sydney with his first troupe of performers early in 1851, Henry Burton developed touring routes throughout Australia's eastern seaboard that periodically brought his National Circus back to Sydney. In fact, Burton's National Circus was the only touring circus to be regularly seen in the city before the 1880s. Burton's last Sydney season, towards the end of 1879, coincided with the Sydney International Exhibition. With competition from all quarters, the season proved a financial disaster for Burton and forced the liquidation of the company and his retirement from the active circus scene. [54]

During the summer of 1883–84, St Leon's Mammoth Circus, which had trekked overland from Adelaide, entertained Sydney. At first, St Leon had difficulty securing ground within the city precincts and was refused the use of Belmore Park by the City Council. [55] Short stands were given in the suburbs of Newtown and Balmain before the company was able to open on ground at the corner of Foveaux and Crown streets, Surry Hills, for a seven-night stand. A small park containing a children's playground occupies the same site today. [56]

Eventually, St Leon secured ground at the south end of Pitt Street, opposite Mr Robertson's coach factory, near the Haymarket, Sydney's customary circus location. [57] St Leon's took receipts of £5,000 during a phenomenal six-week season. [media]The proprietor, Matthew St Leon – the same acrobat, equestrian and dancer who, as John Jones, had first entertained Sydney and its outlying settlements in 1850 – announced he would appear before the public in his 'daring feats of horsemanship' and in his 'celebrated classical drawing-room entertainment' with his three sons. A large number of people gathered at the circus for St Leon's benefit and 'one of the cleverest equestrians' ever to have visited Sydney was received 'with great applause'. [58] The St Leon family continued to entertain Sydney audiences until the 1950s. St Leon's Posing Dogs was a picturesque 'statuary' act seen in vaudeville in the 1920s [media]while The Five Riding St Leons was a feature of Wirth Bros Circus after World War II. A branch of the St Leon family, known as The Honeys, were seen in circus and vaudeville in the 1920s with their acrobatic act before leaving for the United States in 1926 where they rose swiftly from fairground work to vaudeville and even appeared in early television programs. [59]

Rival circus brothers

By the late 1880s, a new mould of Australian circus men – principally, the four Wirth brothers and the two FitzGerald brothers – had emerged, eager to adopt more methodical and innovative ways to meet the demands of an increasingly sophisticated and urbanised population. Although horses and horsemanship remained a central feature of Australian circus programs until the 1960s, the novelties introduced by the Wirths and the FitzGeralds tended to expand the conventional concept of circus by incorporating acts that were 'Wild West' or 'daredevil' in nature or drawn from the music hall.

The Wirths were the musical sons of Johannes Wirth, whose 'celebrated band' of German musicians accompanied a plain and fancy dress ball at the Prince of Wales Theatre and played 'several favourite overtures' in Sydney in May 1856. [60] Johannes Wirth later found employment in the bands which the larger circuses of that era carried to accompany each performance. Over many years of 'circusing' throughout outback Australia, the four sons of Johannes Wirth developed circus skills to complement their musical skills. In 1882, after leaving Ashton's Circus after a 'rough-up' at Goulburn, the four brothers opened a sideshow on Sydney's Haymarket Reserve. The Reserve was used as a market square during the week, but occupied by merry-go-rounds, corn-curers, organ-grinders and 'hurly-burly' tent showmen each Saturday. With admission set at sixpence a head, the Wirths gave seven or eight performances each Saturday for six months, from 1 pm until 11 pm, in a small tent about 12 metres in diameter. [media]When they were not playing as musicians, they were tumblers or contortionists, club-swingers, trapeze artists or horizontal-bar performers. On the first Saturday, the brothers cleared £42. They played on the same location until they could afford to buy several horses and wagons and organise a travelling circus troupe. [61] By the time the brothers returned to Sydney late in 1887, Wirth Bros Circus was Australia's largest. Yet, not all were impressed. Sydney's Mayor compelled the Wirths to open in Newtown, on the city's outskirts, rather on the customary circus site of Belmore Park. Apparently, 'the nobs of Sydney' had petitioned the Mayor over the noise and traffic that the circus would generate. [62]

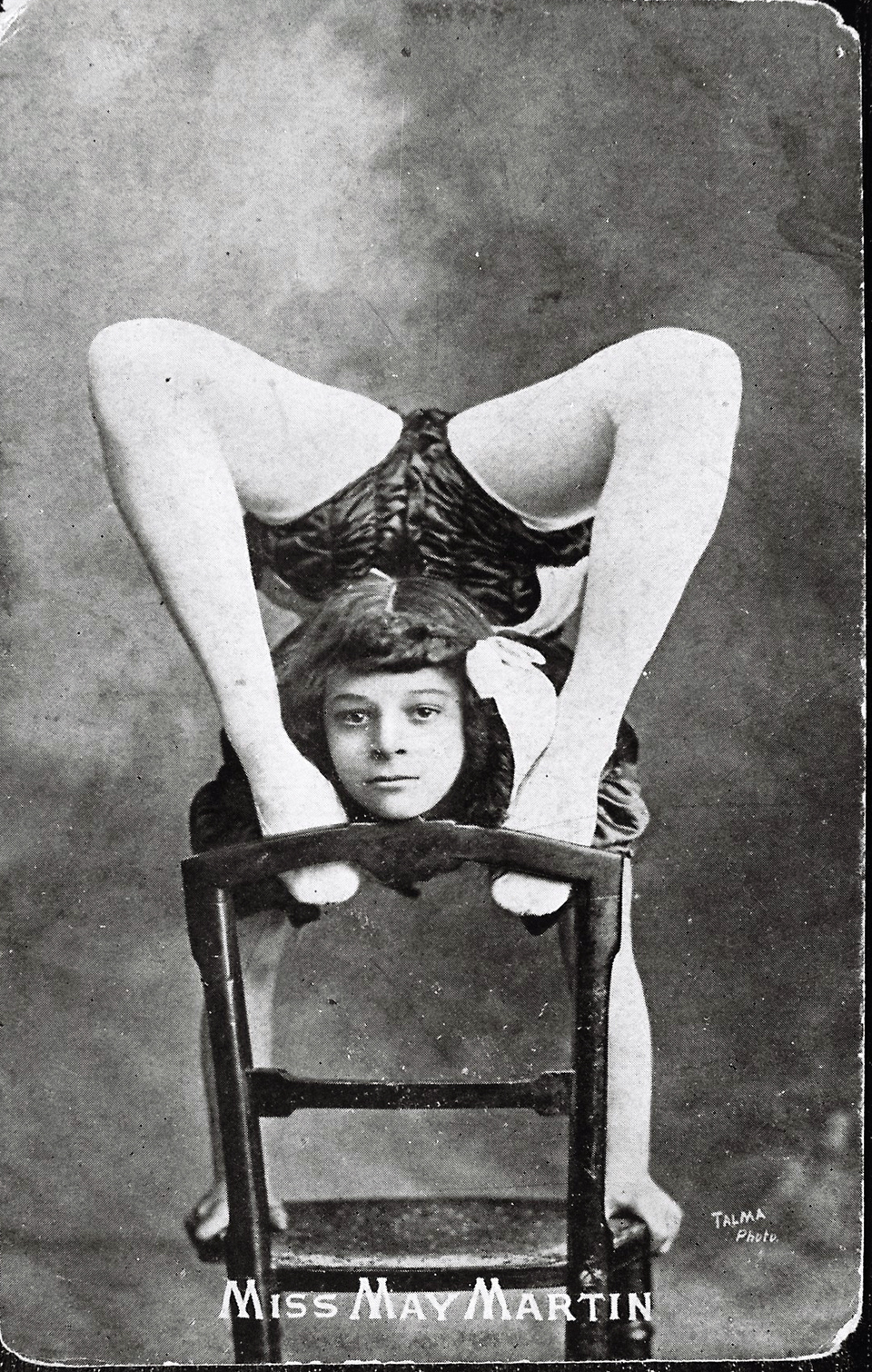

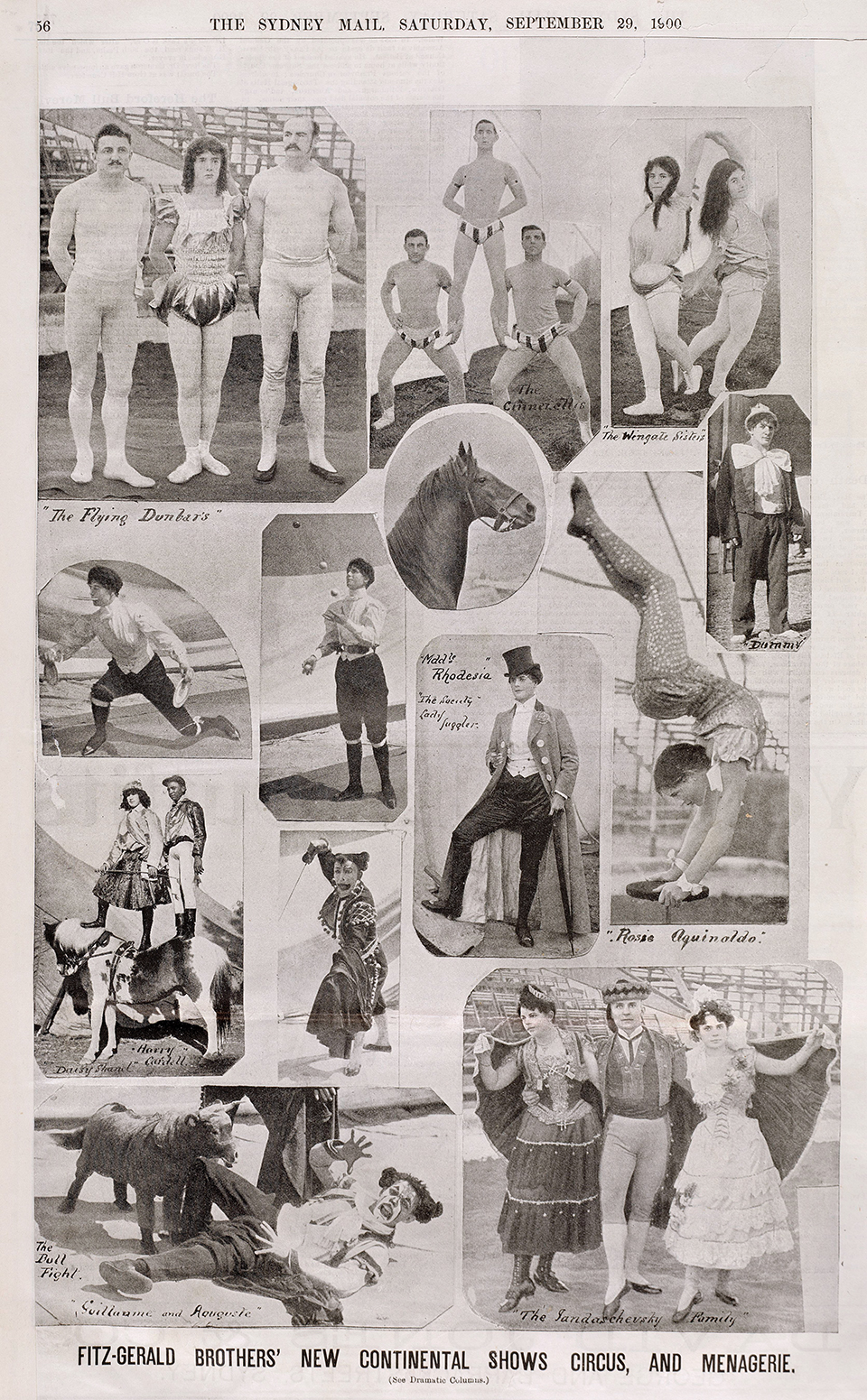

[media]Not far behind the Wirths were the popular FitzGerald brothers, Dan and Tom, who, from modest beginnings in the early 1880s, eventually ran the largest and most popular circus in Australia, for a time at least. They were the brothers of John D FitzGerald, a prominent Sydney barrister, social reformer and Labor parliamentarian. [63] When Wirth Bros Circus left Australia in 1893 for a seven-year-long world tour, FitzGerald Bros Circus was handed the position of Australia's major circus company. [64] Over a period of 14 weeks in 1893, the FitzGeralds delivered Sydney probably its longest-ever circus season and, almost every evening, the FitzGeralds' tent was crowded to capacity with audiences 'moved to repeated outbursts of uncontrollable hilarity'. One evening, the Archduke of Austria, Franz Ferdinand d'Este, and his retinue, who had called in to Sydney aboard a cruiser of the Austro-Hungarian navy during a tour of the world, patronised the circus. The same Archduke's assassination at Sarajevo, 21 years later, triggered the outbreak of World War I. [65] In October 1895, the FitzGeralds introduced their New London Company to Sydney audiences at the Exhibition Building. This consisted of superb artists handpicked from the music halls and circuses of England and the Continent. [66] One of these was the 'talking' horse, Mahomet, who spent a 'busy hour' in the city one day with his trainer, the American, EL Probasco:

Mahomet … walked into the bar at the Australia Hotel beside Mr Probasco as calmly as possible and, emerging a few minutes later, made his way to the establishment of Kerry and Company, George Street, with the object of having his picture taken. There is a stairway 4 ft wide, and containing no fewer than twenty-four steps, leading from George Street to the studio, and after standing at the door for a moment, and looking rather knowingly at several young ladies at the top of the staircase, Mahomet proceeded to climb it. This he did in a couple of moments, without stumbling or faltering in the least. Then he walked up half a dozen or more steps into the camera-room, and the bridle having been removed, his coat was brushed preparatory to sitting for his photo. While the handsome animal was standing complacently viewing the situation, his clever trainer asked him one or two questions. “Tell me how many ladies are in this room”, and quick as thought Mahomet struck the floor five times with his hoof. “How many of these ladies are wearing hats?” One hoof-knock was the answer, and it was given in an instant. Mr Probasco was standing fully 4 ft away from his horse, and made no sign whatever. Mahomet's photograph having been taken, he was saddled, and quietly descended the staircase into George Street. [67]

During the FitzGeralds' return visit to Sydney the following May, another of the New London Company, the London-born high diver, Charles Peart, was fatally injured when he misjudged his plunge from a great height into a small tank of water. Peart was buried in Waverley Cemetery. His fellow artists sponsored the erection of a memorial tombstone over his grave. [68]

The FitzGeralds dressed and bewigged a young Australian apprentice, Ernest McMurtrie, as a girl and presented 'her' as 'Daisy Shand' in equestrian and trapeze acts. Shand's son, Ron, later pursued a career in vaudeville and, in the 1970s, emerged from retirement to play the role of 'Herb', the bumbling septuagenarian in the popular Sydney evening television soapie, No 96.

In 1900, FitzGerald Bros Circus was clearly Australia's leading circus but with the return that year of Wirth Bros Circus from its world odyssey, the former rivalry between these two large circuses was renewed with increasing vigour. Each toured Australia and New Zealand by rail and steamship along standardised routes, with companies of both imported and domestic artistes, menageries of wild animals, large bands of professional musicians and lavish promotion. The two companies increasingly played 'opposition' to each other until a final confrontation in Sydney for the 1905 Easter season. [69]

After the coincidental deaths of Dan and then, in Rangoon, Tom FitzGerald, early in 1906, the circus premiership of Australia was assumed by Wirth Bros Circus by default. Many of Sydney's key civic and theatrical identities augmented the cortege that followed the remains of the popular Dan FitzGerald to his final resting place in Waverley Cemetery. [70] Wirth Bros [media]held the position of Australia's major circus company, through two world wars and a depression, until its final closure in 1963. After relinquishing its lease over the Hippodrome, Wirth's used other buildings for its annual Sydney seasons including, in 1930, George Marlow's Grand Opera House (later the New Tivoli), where the stage was strengthened to support 30 tonnes of elephants. Annual seasons of Wirth's Circus in Sydney in later years were given under canvas in the city's more spacious parks such as Prince Alfred or Rushcutters Bay. Wirth's tents were manufactured by the Sydney firm of Sam Walder who also served as Lord Mayor of Sydney and was the stepfather of William McMahon, a later prime minister of Australia. The Wirths assumed many of the gestures of public goodwill established by the FitzGeralds such as the distribution of hot cross buns and ginger beer to the poor children of Sydney each Easter. [71]

The influenza pandemic that swept the world in the aftermath of World War I reached Australia early in 1919 when returning soldiers brought home strains of the viral infection. For six weeks, all places of public entertainment, including circus, were closed. As a result, in Sydney, the 1919 Easter opening of Wirth Bros Circus at the Hippodrome was cancelled. [72] During World War II, Wirth's Circus was one of the few circuses allowed to operate and then only on a limited scale. Denied the use of rail services need for the war effort, Wirth's travelled by road and on a much reduced scale, its daily progress severely restricted by petrol rationing.

Postwar circus

In 1945, with the end of World War II, the circuses of Australia could once again commence operations unfettered by the petrol, lighting, manpower and transport restrictions of wartime. New circuses emerged to accommodate the public's hunger for entertainment after the privations of wartime.

The original Silver's Circus was organised by Mervyn King and the Hardie family of tentmakers in Sydney in 1946. The professional name of 'Silver' was chosen for the circus, inspired by the neon sign King saw flashing one night outside a Sydney restaurant, The Silver Grill. King had begun his own circus career in 1915 as a seven-year-old acrobat in St Leon's Circus. His circus expertise combined with the financial and technical support of the Hardies proved a winning combination. An official opening was given at Jude's Corner, Rockdale. King took the professional name of Alwyn Silver as 'there had to be a Mr Silver around the show'. Within five years, Silver's Circus was Australia's largest road show and toured every state of the Australian mainland. The company was dissolved at the peak of its success in 1953 but other companies revived the name of 'Silver' in years to follow. After a lifetime of travelling and entertaining Australia and New Zealand, King retired to Sydney. When he died in 2003, aged 95, the Sydney Morning Herald devoted almost an entire page to his obituary. [73]

Another major circus to prosper in the post-war period was Bullen Bros which had its origins in the lion-taming exhibitions that Kiama-born Perce Bullen gave on the showgrounds in the early 1920s. Its spacious tents and numerous, brightly painted trucks and caravans were seen almost every Easter on Sydney's Wentworth Park until the late 1960s. In 1969, the 94-vehicle Bullen Bros Circus gave its final performance at Parramatta. The Bullen family refocussed its commercial interests on a wildlife safari park at Wallacia, west of Sydney, and the regular importation of the Great Moscow Circus in partnership with entrepreneur Michael Edgley. [74]

For all its popularity, the circus had gradually lost ground over the course of the twentieth century, to alternative forms of popular entertainment such as vaudeville and variety from the early 1900s, then cinema from the 1920s, television from the 1950s and, more recently, from the rise of new forms of electronic media such as the internet. To some extent, circus could benefit from these innovations. In the 1920s, for example, circus performers could achieve almost year-round employment by working the vaudeville circuits between circus engagements. In the 1960s, television could deliver circus programs, domestic and foreign to mass audiences. In the 2000s, about 20 per cent of all tickets to domestic circus companies are purchased online. But, overall, circus in Australia, as elsewhere in the world, has been forced in recent decades to redefine itself in order to remain relevant.

From the bush to the city to the world

By the 1900s, if not earlier, circus and other showmen recognised the value of playing Sydney during the Easter period as a prelude to undertaking a tour of regional New South Wales. In Sydney in May 1869, the Agricultural Society of New South Wales held its first annual Easter show, and the event grew to become a popular affair, drawing thousands of country people to the city along the newly constructed provincial railway lines. [75] A successful Sydney season during Easter could go a long way towards spreading word of a circus or other show in advance of its tour of the state. Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, local agricultural and pastoral societies had been formed in almost every town of consequence. Local annual shows not only gathered townspeople together but attracted large numbers from outlying areas to see exhibits of animals, produce, domestic products and machinery. To maximise revenues, itinerant showmen gradually developed touring circuits to follow the various sequences of show towns, into and out of Sydney, and to capitalise on climate and transport factors. An extraordinary range of entertainments, some large and others small, some sophisticated and others crude, travelled from one country show to another. [media]As well as circus, there were theatre and vaudeville tent shows, concert parties, boxing troupes, magicians, marionette shows, merry-go-rounds, carnivals, menageries, snake charmers, tattooed women and so on. At a less reputable level, there were medicine shows, confidence tricksters, card sharps, pickpockets and cheapjacks.

A fine circus seen regularly in country towns in the 1910s was Colleano's All-Star Circus. This circus actually grew out of the boxing tent show that Irish-Australian showman Con Sullivan had toured out of Sydney and through the country show towns in the 1890s. Early in the 1900s, Sullivan began to see a circus as a more secure business proposition to support and employ his growing family of boys and girls. While settled at Lightning Ridge, he and his Narrabri-born Aboriginal wife, Julia, trained their young children in basic circus skills and, in 1910, the family started on the road with its own circus. [media]The family adopted the professional circus name of Colleano and, to camouflage their partly Aboriginal identity, called themselves The Royal Hawaiians. The family laboured hard and by 1918, travelling the eastern states in its own 'special' train, had the largest circus in Australia after Wirth's. Although Colleano's All-Star Circus never came into central Sydney, it played the major suburbs, including a lengthy season at Strathfield in 1921.

The ten Colleano children performed in the circus as acrobats, trapeze artists, wirewalkers, bareback riders and musicians. All were exceptionally talented performers but the most promising was the third child, Lismore-born Con Colleano (1899–1973), a wirewalker. Con Colleano went on to achieve international fame with his dancing and acrobatics on the tightwire, the highlight of which were extraordinary backward and forward somersaults. He had laboured for five years to perfect a forward somersault on the tightwire, previously thought impossible, as the performer loses sight of the wire as he tucks his head down and rotates his body through the air. Eventually, by developing an intuitive 'sixth sense', he brought off the fabulous trick at practice outside the family circus one afternoon in Sydney in 1919. Thereafter, he gradually refined and perfected the act for public performance. After the Colleanos closed their circus in 1922, Con performed in vaudeville and was seen at popular Sydney venues, including the Tivoli Theatre of Sir Jack Musgrove, and its chief rival, Sir Ben Fuller's National Theatre. Con's wife-to-be, Winnie Trevail, a vaudeville soubrette at the time, later recalled many years later how the young Con gave his audition at the Tivoli:

Con practiced this act and he knew he had something ... They played all the bush towns and everything. And he knew that he'd have to do something to show his act and get somewhere. So he came down to Sydney to the Tivoli and he told Jack Musgrove 'I do a wire act and I'd like you to have a look at it' ... Well of course he went in and caused a sensation. They'd never seen anything like it, you know, even in this country ... [media]He asked for quite a salary in those days. I think it was about £80 pounds a week, or something, which was a tremendous salary in those days, you know ... Anyhow, Musgrove saw what he had and he booked him, so he played the Tivoli and then I was playing next door at the National Theatre at that particular time. And then … after he finished with the Tivoli then Fullers booked him. [76]

By 1925, Con Colleano was 'The Australian Wizard of the Wire', a prestigious 'center ring' attraction with the huge, four-train Ringling Bros and Barnum & Bailey circus, America's largest circus. [media]He was one of the highest paid and most popular performers working the circus and vaudeville circuits of North America and Europe throughout the late 1920s and 1930s. Con made a brief return visit to Sydney in 1937, when he was featured on the tightwire in the production of Three Cheers for the Red, White and Blue , a patriotic [media]revue at the New Tivoli, under the management of Frank Neill. [77]

One of the greatest circus artistes of all time, May Wirth, bore the prestigious Australian circus name of 'Wirth', but she was actually born May Zinga when she first saw the light of day at Bundaberg, Queensland, in 1894. Adopted by the Wirth family as a seven-year-old, May was trained in all the circus arts but specialised in bareback riding. In Wirth's Circus in Sydney in April 1911, she 'rode and drove eight ponies, and turned somersaults on a cantering grey'. [78] This flattering, though passing, description gave little suggestion of the depth of her talent as an equestrian. Less than a year later, May made her American debut in Barnum & Bailey's Circus at Madison Square Gardens, New York, billed as the 'world's greatest lady bareback rider'. [79] Overnight, she became a sensation throughout the United States and today is regarded as one of the greatest riders in the international annals of circus. [80]

A later generation of the Ashton circus family, six brothers and a sister, comprised the acrobatic troupe of the Seven Ashtons, popular throughout the United States and Europe during the late 1940s and early 1950s. During the Depression in the 1930s, they left the main Ashton circus and developed their own acrobatic act in the backyard of their Sydney home, a little house in Newtown. In the backyard, the children practised spinning brooms with their feet and balancing an old armchair. They gradually developed a stage performance where one artist, after a series of somersaults in mid-air, landed on the upturned feet of another. Their specialty became a 'Risley' act, named for its originator, the American gymnast, Richard Risley Carlisle, who had exhibited these performances in Sydney during his visit in 1861. In a Risley act, one or more performers, lying on his back, juggled smaller members of the troupe with his feet. Eminent British circus historian Antony Hippisley Coxe described the Seven Ashtons' act as the best Risley act he had ever seen. The Seven Ashtons toured the United States with Sonja Henie's famous ice show and appeared in a Royal Command performance before George VI at the London Coliseum. [81]

American and other circus visitors

In the decades before the American Civil War (1861–65), the United States was already prominent as a seafaring nation. Her ships sailed every ocean and visited the great seaports of the world. Enterprising American circus men, ever on the lookout for fresh territories to visit and exploit, first ventured to foreign lands in this era. [82]

Since the visit in 1792 of English equestrian John B Ricketts and his troupe, circus entertainments proved popular in the new United States of America. Numerous small companies travelled the back roads of the eastern states and then moved westwards with the spread of settlement. The American circus men were both adventurers and innovators. They made liberal use of the riverboats for transport and, in the 1850s, organised the first railroad circuses. They toured through the islands of the Caribbean, Central and South America. American circus troupes reached Australia on the eve of the gold rush of the 1850s. The first, John Sullivan Noble's troupe, opened in 1851 at the Olympic Circus at the rear of The Painter's Arms, an inn in Castlereagh Street, having sailed from Cape Town by way of Adelaide a few months earlier. [83] Unwittingly, Noble precipitated more than 60 years of almost continuous seaborne circus traffic between Australia and the United States and the mutual transfer of similar, yet different, alternative cultural values. [84]

During the Civil War, America's once vibrant domestic circus activity was subdued and interest in trans-Pacific intercourse waned. [85] Soon after the cessation of hostilities however, the circus men James Cooke, Omar Kingsley and John Wilson met in San Francisco to organise a company for an Australasian tour. Kingsley was famous for his performance in female attire as the renowned 'equestrienne' Ella Zoyara, and thus was the circus named Cooke, Zoyara & Wilson's Great World Circus. Crossing the Pacific and giving performances in Honolulu, Tahiti and Auckland, the company arrived in Sydney in March 1866. Large crowds gathered around a site in Pitt Street, the same now occupied by the General Post Office, as a 'chaotic mass' of timber, gas pipes, chairs, carpets and canvas were gradually transformed into a temporary circus building. [86] The latest American examples of acrobatic bareback riding, vaulting, leaping, gymnastics and clowning were much appreciated by audiences numbering as many as 3,000 people. The Governor of New South Wales, Sir John Young, and Lady Young attended a 'grand farewell night' before Cooke, Zoyara & Wilson left for other colonies and India. [87] Since John Wilson, alone, reputedly cleared US $100,000 from the tour, the interest of other American circus men in an Australasian tour could not but be awakened. [88]

The unification of America's eastern and western states by rail in 1869 was a fillip to trans-continental commerce including circus. In 1870, the Pacific Mail Steamship Company inaugurated a regular shipping service between Sydney and San Francisco with a passage time of as few as 30 days. [89] For many American circus men, eager to explore new territory and escape adverse economic conditions at home, the feasibility of visiting the 'fabled land' in the south seas improved dramatically. [90] The most intense intercourse occurred during the period 1873–92 when hardly a year passed without Australia being visited by a major American circus or Wild West show. Most commenced or concluded their tours in Sydney. [91] [media]The first to arrive in this era was Chiarini's Royal Italian Circus, a substantially American company despite the Italian birthright of its proprietor. In Sydney, Chiarini's leading equestrian, George Holland, updated local audiences with the latest American riding tricks, including the incredible forward somersault on the back of a moving horse. [92]

Three years after Chiarini came Cooper, Bailey & Co's Great International Allied Shows. The several advance agents of Cooper, Bailey & Co diligently carried out their work in adorning Sydney with bills. Upwards of 15,000 people (out of a population of some 135,000) lined the shores of Sydney Harbour to witness the arrival of the 'Yankee Wild Beast Show' by the Pacific Mail Steamship Co's City of Sydney one morning early in December 1876. [93] Although Sydney's 'unequalled' port facilities facilitated the rapid unloading of the circus properties, it nevertheless took a week for Cooper, Bailey & Co to complete the erection and fit-out of its 'new and commodious building' on the Haymarket Reserve. [94] The company's press agent, WG Crowley, wrote to the New York Clipper to say that 'there is plenty of life here [in Sydney], though in business matters the people are slow and old-fashioned'. [95] Nearly a year later, on 26 November 1877, Cooper, Bailey & Co returned to Sydney to inaugurate a second Australian tour, its tents erected this time on Bell's Paddock, at the corner of College and William Streets. [96] After returning to the United States, Cooper, Bailey & Co merged with the circus of PT Barnum, to become known as Barnum & Bailey's. In 1919, Barnum & Bailey's was merged with Ringling Bros to form the present-day Ringling Bros and Barnum & Bailey's Greatest Show on Earth.

[media]One of Cooper, Bailey & Co's chief competitors in the United States was William Washington Cole (1835–1915), the proprietor of a major railroad circus. In November 1880, after some four years of preparation and planning, Cole brought his circus – WW Cole's Concorporated Shows – across the Pacific from San Francisco. The Australasian tour began in Auckland and finished in Sydney six months later, in April 1881. Cole's huge American circus tent accommodated two rings and up to 6,000 people for a single performance. This was perhaps three times as many people as the largest Australian circus tents of the day could accommodate, but comfort and value for money were duly sacrificed – as many of Cole's Sydney patrons found to their annoyance. [97]

In contrast to the Americans, the visits of major English circus companies to Australia were few and none travelled directly from England because of the distance and shipping cost and the revenue-earning time that would be lost in transit. Nevertheless, some English circus companies managed to reach Australia from intermediate points. When Harmston's, a circus organised in San Francisco under English management, opened in the Crystal Palace Rink in Sydney's York Street on 15 May 1890, it presented the daring rider Gilbarto (the nom d'arena of an English rider, Gilbert Eldred) who was loudly cheered for his 'remarkable' backward and forward somersaults on a bareback horse. [98] After several years touring India, Burma, China, Japan and Java, this company opened in Sydney again in April 1898, now announced as Harmston's Grand Circus & Royal Zoologia. [99] The only other English circus of consequence to visit Sydney was Bostock & Wombwell's Novelty Circus & Complete Menagerie, the management of which had decided to undertake a tour of Australia and New Zealand after visiting South Africa. Bostock & Wombwell's opened in Sydney in July 1906 and later disbanded in Melbourne. [100]

Another large American circus, Sells Bros, commenced its six-month tour of Australia's eastern colonies in Sydney in November 1891. Some 10,000 miles from home, Sells Bros mischievously expropriated Barnum & Bailey's jealously guarded subtitle of 'the greatest show on earth' to impress itself upon its Australian patrons. [101] The difficulties the Sells encountered in negotiating stringent colonial quarantine regulations on arrival in Sydney – the company had to open on Moore Park without horses – may have discouraged American circus proprietors from mounting tours of Australasia thereafter. [102] In any case, the Australian colonies were soon to enter into a severe economic depression while American circus managers, anxious to maintain their competitive position at home, appear to have lost their earlier appetite for overseas touring.

The last large American circus to visit Australia was Bud Atkinson's American Circus and Wild West which arrived from San Francisco to open on Moore Park in December 1912. [103] Atkinson had served as managing director of JD Williams's huge cinema and amusement complex in George Street in 1911–12 until a falling-out ended the association. [104] Atkinson returned to the United States and hastily organised an elephantine company of circus artists, cowboys and Red Indians, for an Australian tour. Located on Moore Park, Atkinson's dynamic approach to show business took Sydney by storm:

Mrs Bud Atkinson ... paid the salaries and all the expenses of the circus out of the concessions. They sold that many concessions – sideshows, peanuts, drinks, anything you like to mention, souvenirs, American cowboy caps, anything to remember the circus by. [105]

However, Atkinson's subsequent tour proved a disaster since his company was too large and cumbersome to be operated economically through regional Australia. Closing up in Melbourne after only a few months' touring, Atkinson's artists had to find their own way home. [106] [media]After Bud Atkinson's American Circus & Wild West Show, there are no confirmed visits to Sydney of large and complete circus companies, from the United States or elsewhere until 1965 when the Great Moscow Circus was brought to Sydney by Perth-based entrepreneur, Eric Edgley, in partnership with the Bullen circus family. [107]

One visiting individual circus artist proved to have almost as much box-office power – alone – as an entire circus. [media]This was the French outdoor rope-walker, Jean Francois Gravelet, better known as Blondin. In 1859, Blondin had secured everlasting world fame after walking a tightrope, about 360 metres long and 60 metres high, over Niagara Falls, New York, before some 50,000 spectators. [108] During Blondin's visit to Sydney in 1874, special excursion trains brought people from country towns to see his tightrope performances which were given inside a huge canvas enclosure erected on the Domain. The enclosure, 'the largest in the world', took Blondin and his 12 assistants three days to prepare. [109]

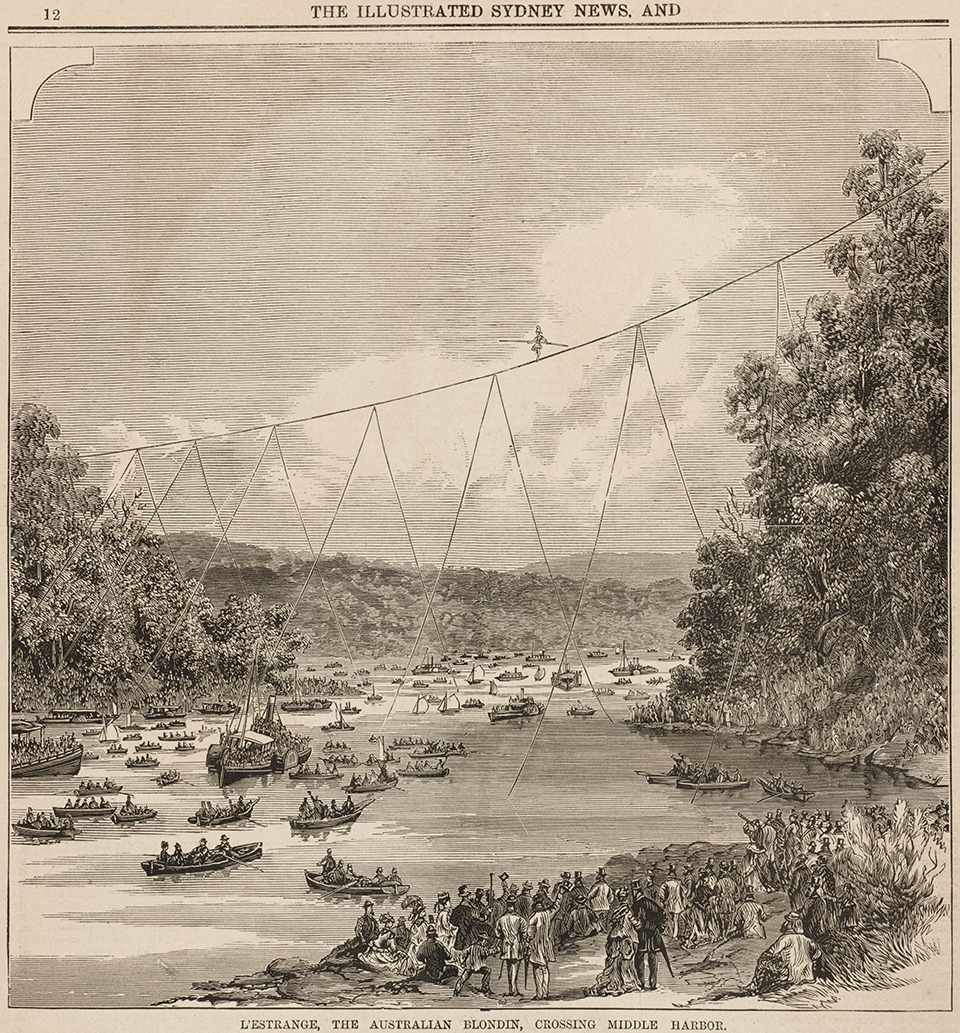

Blondin spawned a host of colonial imitators. [media]The most outstanding of these appears to have been Harry L'Estrange who, billing himself as 'The Australian Blondin', walked a tightrope across Sydney's Middle Harbour on 18 April 1877. [110] We do not read again of public ropewalking exhibitions of the calibre of Blondin and L'Estrange until the appearance of another Frenchman, Philip Petit, almost a century later. In Sydney early one morning in 1973, Petit walked a tightwire (surreptitiously put in place during the night) between the southern pylons of the Harbour Bridge and reduced the peak-hour traffic to a crawl as astonished motorists slowed to catch a glimpse. [111]

Contemporary circus

Some fundamental changes to the Australian circus 'landscape' have appeared since the 1970s. Although circus has remained a highly popular form of entertainment, it has effectively bifurcated into two distinct streams, the conventional circus on the one hand, which retains essential elements, and the newer contemporary circus movement which exhibits a more theatrical flavour and actively eschews the use of animals in performance. Each year, Sydney is typically entertained by at least one of each style of circus.

Unquestionably, the most famous of Australia's contemporary circus groups is Circus Oz, originally conceived in Melbourne in March 1978. While emulating some of the features of traditional circus (tents, rings, clowns and so on), and rejecting others (especially animals) the members of Circus Oz injected elements of their own, such as popular music, mainstream theatre and satire so as to produce something more attuned to the needs of a contemporary audience. Circus Oz gave its first Sydney season in 1979 – a sell-out – at the (since-demolished) Paris Theatre. Since then, Circus Oz has played to Sydney audiences on numerous occasions. Another visitor has been Australia's premier youth and community circus group, Flying Fruit Fly Circus. Based in the twin towns of Albury-Wodonga, the Flying Fruit Fly Circus was a feature of the Sydney 2000 Olympic Arts Festival. [112] The extraordinary developments in mass international transport now render Sydney accessible by the world's major contemporary circus groups, such as Cirque du Soleil from Canada. These modern circus enterprises, fresh and innovative, have reignited the Sydney public's appreciation for and fascination with human acrobatic feats, without the need for animal acts typical of earlier circus forms.

Conclusion

While economics has long denied Sydney the luxury and prestige of its own permanent circus establishment, the historical record clearly shows that the city enjoys a good circus when it comes: hardly a year has passed in the last 160 when Sydney has not been visited and entertained by a major circus, even several at the same time. On a practical level, the city's accessibility by land and sea (and later, air), its temperate climate and attractive parklands have been natural inducements for visiting circuses. Its strategic location has started and finished regional and wider Australasian circus tours, whether undertaken by local companies or by companies visiting from overseas.

Judging by the growing storm of circus activity taking place around Australia today, much of it in Sydney – countless circus groups, a federally funded national circus school in Melbourne and regular imports and exports of circus activity in one form or another – circus in Australia is finding a new meaning and relevance. Circus in Australia lives and, from all appearances, has an exciting future. And, as veteran Australian circus man Doug Ashton has often said, as long as there are children, there will always be a circus.

Notes

[1] K Webber (ed), Circus! The Jandaschewsky story, Powerhouse Publishing, Sydney, 1996

[2] G Speight, A history of the circus, Tantivy Press, London, 1980, pp 1ff

[3] R Manning-Sanders, The English circus, Werner Laurie, London, 1952, p 20

[4] K Chesney, The Victorian underworld, Penguin Books Ltd, Melbourne 1972, p 74

[5] H Stoddart, Rings of desire: Circus history and representation, Manchester University Press, Manchester UK, 2000, p 50

[6] Sydney Herald, 16 December 1833

[7] R Waterhouse, Private pleasures, public leisure: A history of Australian popular culture since 1788, Longman, Sydney, 1995, p 44

[8] Sydney Gazette, 12 August 1841

[9] Sydney Herald, 26 January 1842

[10] A Weiner, 'The short unhappy career of Luigi Dalle Case', Educational Theatre Journal, 1975, vol 27, pp 77–84

[11] Archives Office of Tasmania, CSO 24/4/58; M St Leon, 'Horseman or no horseman: Circus activity in Van Diemen's Land, 1847–51', Tasmanian Historical Research Association Paper & Proceedings, vol 55 no 2, pp 86–107

[12] Hobart Town Courier, 1 April, 26 August 1848

[13] N Fernandez, Circus Saga – Ashton's, Ashton's Circus, Sydney, 1970, p 15

[14] Sydney Morning Herald, 30 October 1850

[15] Bell's Life in Sydney, 12 January 1850

[16] Sydney Sportsman, 7 February 1906

[17] Sydney Morning Herald, 15 October 1850

[18] J Cannon with M St Leon, Take a drum and beat it: The story of the astonishing Ashtons, 1848–1990s, Tytherleigh Press, Sydney, 1994, p 15

[19] Sydney Morning Herald, 24 December 1850

[20] Australian Town & Country Journal, 3 August 1904

[21] Sydney Morning Herald, 27 February, 1 May 1851, 4 June 1852

[22] Sydney Morning Herald, 29 August 1851

[23] Australian Town & Country Journal, 3 August 1904

[24] Sydney Morning Herald, 18 April 1851

[25] Maitland Mercury, 1 October 1851

[26] Maitland Mercury, 30 August 1851

[27] R Thorne, Theatre buildings in Australia to 1905: From the time of the first settlement to the arrival of cinema, two volumes, Architectural Research Foundation, University of Sydney, 1971, p 125

[28] Sydney Sportsman, 8 January 1908; New York Clipper, 15 August 1863, 26 November 1892, 11 November 1911; S Thayer, Annals of the American circus, vol III, 1848–60, Dauven & Thayer, Seattle USA, 1992, p 99; unsourced newspaper clipping, New Yorkxe "New York", 24 November, 1908; M St Leon, 'Melville, James', in P Parsons (gen ed) with V Chance, Companion to Theatre in Australia, Currency Press in association with Cambridge University Press, Sydney, 1995, pp 361–62

[29] J Askew, A voyage to Australia and New Zealand, Simpkin, Marshall & Co, London, 1857, pp 105–06

[30] Sydney Morning Herald, 6 April 1852

[31] Bell's Life in Sydney, 10 April 1852

[32] Bell's Life in Sydney, 17 April 1852

[33] Sydney Spectator, 5 February 1908

[34] Sydney Morning Herald, 18 April 1851

[35] Sydney Morning Herald, 28 July 1852

[36] Sydney Morning Herald, 23 October 1854

[37] Sydney Morning Herald, 22 May 1855

[38] M St Leon, 'Celebrated at first, then implied and finally denied: the erosion of Aboriginal identity in circus, 1851–1960', Aboriginal History, No 32, pp 63–81

[39] E Irvin, Dictionary of Australian theatre, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1985, p 173; E Irvin, Theatre comes to Australia, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 1978, p 231

[40] E Irvin, Dictionary of Australian theatre, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1985, p 283

[41] W L Slout, Olympians of the sawdust circle: A biographical dictionary of the nineteenth century American circus, The Borgo Press, San Bernardino California USA, 1998, p 102

[42] Sydney Morning Herald, 23 May 1871

[43] Sydney Morning Herald, 25 May 1871

[44] Sydney Sportsman, 30 November 1910

[45] Australian Town & Country Journal, 11 July 1874

[46] Sydney Morning Herald, 1, 3 April 1916

[47] G Wirth, 'Under the big top: The life story of George Wirth, circus proprietor, told by himself', Life, 15 May 1933

[48] P Burke, Popular culture in early modern Europe, Ashgate, Aldershot UK, 1994, p 97

[49] Sydney Morning Herald, 25 February 1851

[50] Australian Town & Country Journal, 3 August 1904

[51] Maitland Mercury, 28 December 1853; K Webber (ed), Circus! The Jandaschewsky story, Powerhouse Publishing, Sydney, 1996, p 12

[52] Maitland Mercury, 28 December 1853

[53] REN Twopeny, Town life in Australia, 1883, Penguin Books, Sydney, reprinted 1974, pp 219–20

[54] Australian Town & Country Journal, 3 August 1904

[55] Evening News, 7 January 1884

[56] Sydney Morning Herald, 6 December 1883

[57] Sydney Morning Herald, 10 December 1883

[58] Sydney Morning Herald, 5 January 1884; M St Leon, 'St Leon, Matthew (1826?–1903)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, supplementary volume, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2005, p 349

[59] M St Leon, 'Honey, Neredah Daisy St Leon (1879–1960)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 14, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1996, p 483

[60] Sydney Morning Herald, 24 May 1856

[61] G Wirth, Round the world with a circus: Memories of trials, triumphs and tribulations, Troedel & Cooper Pty Limited, Melbourne, 1925, p 23ff

[62] Sydney Morning Herald, 19 December 1887

[63] B Nairn, 'Fitzgerald, John Daniel (Jack) (1862–1922)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 8, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1981, pp 513–15; M St Leon, 'FitzGerald Brothers' Circus', in P Parsons (gen ed) with V Chance, Companion to Theatre in Australia, Currency Press in association with Cambridge University Press, Sydney, 1995, pp 228–29

[64] G Wirth, Round the world with a circus: Memories of trials, triumphs and tribulations, Troedel & Cooper Pty Limited, Melbourne, 1925, p 64ff

[65] Bulletin, 27 May 1893; Sydney Morning Herald, 29 May 1893

[66] Sydney Morning Herald, 21 October 1895

[67] Evening News, 2 November 1895

[68] Sydney Morning Herald, 9 May 1896

[69] Sydney Morning Herald, 15 April 1905

[70] Sydney Morning Herald, 15 April 1905; Daily Telegraph, 21 April 1906

[71] M St Leon, 'Wirth, Philip Peter Jacob (1864–1937)' and 'Wirth, George (1867–1941)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 12, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1990, pp 544–45

[72] Australian Variety, undated clipping, 1919

[73] M St Leon, The silver road: The life of Mervyn King, circus man, Butterfly Books, Springwood, 1991, pp 194ff; Sydney Morning Herald, 17 May 2003

[74] M St Leon, 'Bullen Brothers' Circus', in P Parsons (gen ed) with V Chance, Companion to Theatre in Australia, Currency Press in association with Cambridge University Press, Sydney, 1994, pp 113–14; M St Leon, 'Bullen, Alfred Percival (1896–1974)' and 'Bullen, Lillian Ethel (1894-1965)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 13, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1993, pp 294–95

[75] R Brown, Collins milestones in Australian history: 1788 to the present, Collins, Sydney, 1986, p 283

[76] W Colleano, in M St Leon, Australian circus reminiscences, the author, Sydney, 1984, pp 204–05

[77] For a complete biography of Con Colleano, see M St Leon, The wizard of the wire: The story of Con Colleano, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 1993

[78] Sydney Morning Herald, 3 April 1911

[79] New York Clipper, 30 March 1912

[80] M St Leon, 'Wirth, May Emmeline (1894-1978)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 12, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1990, p 544

[81] N Fernandez, Circus Saga – Ashton's, Ashton's Circus, Sydney, 1970, p 15 pp 54–57

[82] CG Sturtevant, 'Foreign tours of American circuses', Billboard, 2 July 1927

[83] South Australian Register, 12 March 1851; Sydney Morning Herald, 19 September 1851

[84] M St Leon, 'Yankee circus to the fabled land: The Australian-American circus connection', in Journal of Popular Culture, vol 33, no 1, Summer,1999, pp 77–89

[85] LG Churchward, Australian and America, 1788-1972: An alternate history, Alternate Publishing Cooperative, Sydney, 1979, p 199

[86] Sydney Morning Herald, 5, 6, 31 March 1866; Sydney Sportsman, 26 October 1910

[87] Sydney Sportsman, 9 January 1907

[88] New York Clipper, 14 November 1868

[89] R Brown, Collins milestones in Australian history: 1788 to the present, Collins, Sydney, 1986, p 287

[90] WG Crowley, The Australian tour of Cooper, Bailey & Co's Great International Allied Shows, Thorne & Greenwell, Brisbane,1877, p iii

[91] M St Leon, 'Long voyages and muscular vigour: Maritime themes in Australia's circus history', The Great Circle, Vol 31, No1, pp 30–58

[92] Sydney Morning Herald, 18 June 1873

[93] Anon, Around the world in three years, replete with romantic incidents, thrilling adventures and startling episodes, Cooper, Bailey & Co, [USA], 1880, unpaged

[94] Sydney Morning Herald, 18 December 1876; Anon, 1880, unpaged

[95] New York Clipper, 20 January 1877

[96] Sydney Morning Herald, 26 November 1877

[97] Sydney Morning Herald, 11 April 1881

[98] Sydney Morning Herald, 17 March 1890

[99] Sydney Morning Herald, 2 April 1898

[100] Sydney Morning Herald, 7 July 1906

[101] Australian Town & Country Journal, 14 November 1891

[102] Anon, 'William E 'Bud' Gorman', in Circus Scrap Book, No 5, January 1930, pp 4–7

[103] Sydney Morning Herald, 10 December 1912

[104] Sun, 23 April 1911; New York Clipper, 21 September 1912; Bulletin, 27 June 1912

[105] AF St Leon, in M St Leon, Australian circus reminiscences, the author, Sydney, 1984, p 158

[106] Theatre, 2 June 1913

[107] C Higham, 'Death of a circus?', Bulletin, 27 July 1963

[108] A Hippisley Coxe, A seat at the circus, The Macmillan Press Limited, London, 1980, p 165; J Culhane, The American circus: An illustrated history, Henry Holt & Company, New York, 1990, p 61

[109] Australian Town & Country Journal, undated clipping, 1874

[110] Australian Town & Country Journal, 7 April 1877

[111] P Petit, On the high wire, Random House, New York, 1985, p 117

[112] Sydney Organising Committee for the Olympic Games, 'Circus in Australia', in Fusion: The Flying Fruit Fly Circus, Olympic Arts Festival Program, Sydney, August, 2000

.