The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Returned Soldiers on the Ultimo Presbyterian Church Roll of Honour

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Returned Soldiers on the Ultimo Presbyterian Church Roll of Honour

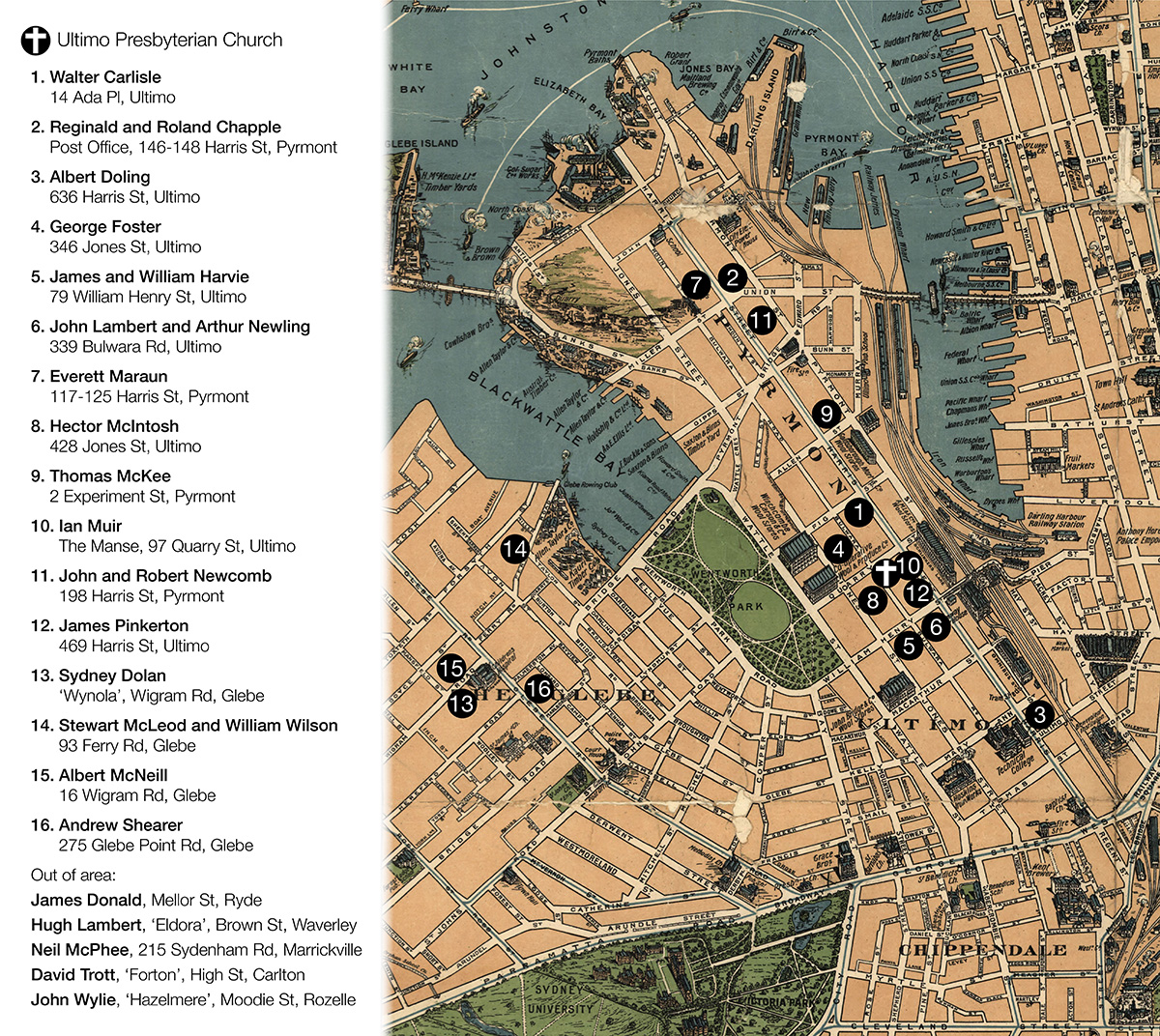

[media]The Ultimo Presbyterian Church Roll of Honour, now housed in the foyer of the Ultimo Community Centre, bears the names of 36 men who enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) in World War I. Only 26 are readily identifiable but service records reveal that 22 of them came home. The stories of their war service, heroism, larrikinism and injuries are poignant and hint at the hardships they would face when they returned to their communities.

Brave young men

[media]Of the 36 men listed on the Ultimo Presbyterian Church honour roll, 26 can be identified with reasonable certainty. Ten had common names, such as Allen, Brown, Jackson and White, making it difficult to identify them or their connection with Ultimo. Ten lived in Ultimo at the time of their enlistment and 11 lived in the surrounding suburbs of Pyrmont and Glebe. The majority, 22 in total, were under 25 years old. Birth records indicate eight of them misrepresented their age and five of those were just 17 years old. The youngest were Walter Thomas Carlisle, who listed his age as 18 years and 10 months but was actually 16, and Arthur Sidney Newling, who listed his age as 19 and 11 months when he enlisted in February 1915 but had actually been born in 1899. He may have been only 15. [1]

These men came from a variety of occupations. There were clerks, labourers and ironmoulders as well as a bank messenger, farmer, carpenter, joiner, boilermaker, cook and a baker. They served in a number of units such as the Field Ambulance, Artillery Column, Army Service Corps and Anzac Cyclist Battalion.

For some of the men, their connection to the Ultimo Presbyterian Church is plain. Others appear to be linked by place of birth, address and/or occupation. For example, four of the 26 men identified themselves as Church of England on their service record but they lived in Ultimo or adjoining suburbs. Brothers Roland and Reginald Chapple had lived at the Post Office in Pyrmont, where their father was postmaster general until at least 1912, before the family moved to the post office on Darling Street, Balmain. [2]

Mysteries of the honour roll

At least two of the men had no clear connection with either the Presbyterian Church or Ultimo. Neil Campbell McPhee, a bridge-builder originally from Glasgow, lived in Marrickville. [3] David Trott, a 24-year-old cook, also from Glasgow, lived in the southern Sydney suburb of Carlton. [4] He fought in Gallipoli and on the Western Front before he faced a court-martial for a self-inflicted wound, having shot away a thumb and forefinger on both of his hands. [5] Perhaps the enthusiasm for the honour roll and the push for further enlistments led to erroneous inscriptions – a Redfern man told the gossip magazine, Table Talk , in 1918: 'I don't know how the lists are compiled, but my boy is on honor boards for districts he never lived in in his life. I suppose they all want a big list'. [6]

One name on the Ultimo honour roll stands out above all; 'E Scranchki' is inscribed on the third panel, an unusual and probably completely misspelt name. His identity remains a mystery. He may have been a seaman named Militan Schatkowski. [7] Schatkowski was born in Lithuania and worked on ships sailing to and from various Australian ports in the lead up to his enlistment in the AIF in October 1914. [8] Service records often obscure ethnic and cultural diversity as the tension of war compelled many to adopt aliases to conceal their 'foreign-sounding' names. [9] Before the end of the war Schatkowski adopted the surname of his new wife and throughout his service record his original surname is crossed out and replaced with 'Oldham'. Interestingly, he listed his religion as Presbyterian in his service record, however, Schatkowski lived in Newcastle and apart from being in port in Sydney in 1914, had no clear links to Ultimo and the church.

Whatever their connections to the church and suburb of Ultimo, the names on the honour roll reveal the diversity of the community and complexity of war service. When investigated further, the Ultimo Presbyterian Church honour board exposes how the war drastically transformed communities.

A young labourer

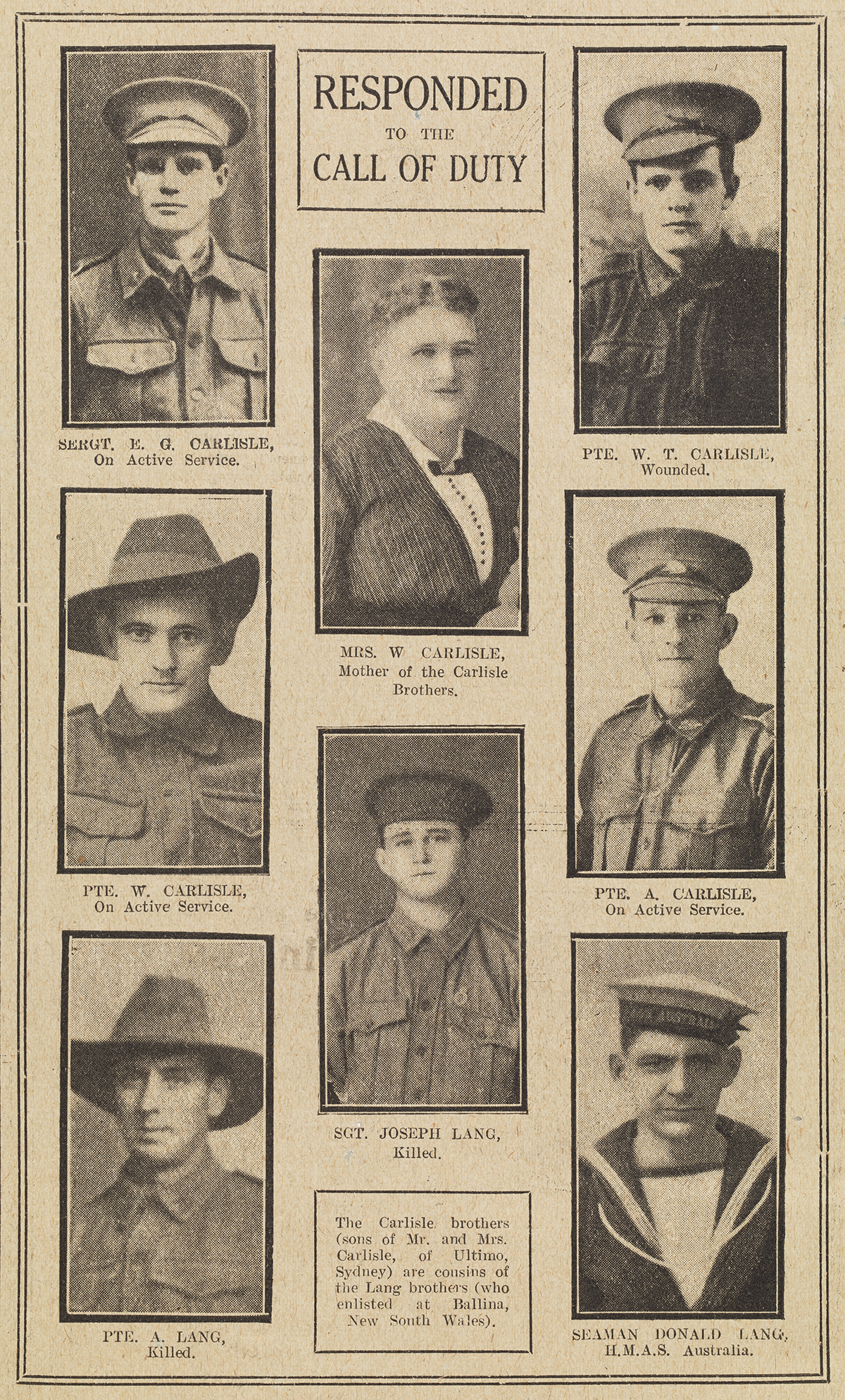

Sixteen-year-old Walter Carlisle[media] was keen to follow his four older brothers so he joined the 19th Battalion on 5 December 1915, claiming to be 18 years old with a note signed by his parents. [10] In a move that was intended to reflect the commitment of Australian families, and designed to rally patriotic support for the war, the Sunday Times published images of Carlisle, his brothers and mother Flora under the proud heading 'Mrs Carlisle, of Ultimo, and Her Five Fighting Sons'. [11] Six months later the Sydney Mail followed suit and published photographs of the family under the headline 'Responded to the Call of Duty'. [12] Underneath Walter Carlisle's image in the Sydney Mail appears the word 'wounded'. In reality, Carlisle was at the 39th General Hospital in Le Havre in France, diagnosed with venereal disease. He spent a total of 65 days receiving treatment. [13]

Carlisle joined the 60th Battalion in February 1918 and was wounded in action five months later, suffering a severe shrapnel wound to his left arm. [14] After convalescing in an English hospital in Dartford he embarked for Australia in December 1918 and was discharged in June 1919. [15] Inexplicably, Walter is the only one of the four Carlisle boys to be listed on the honour roll.

A rebel with an unselfish devotion to duty

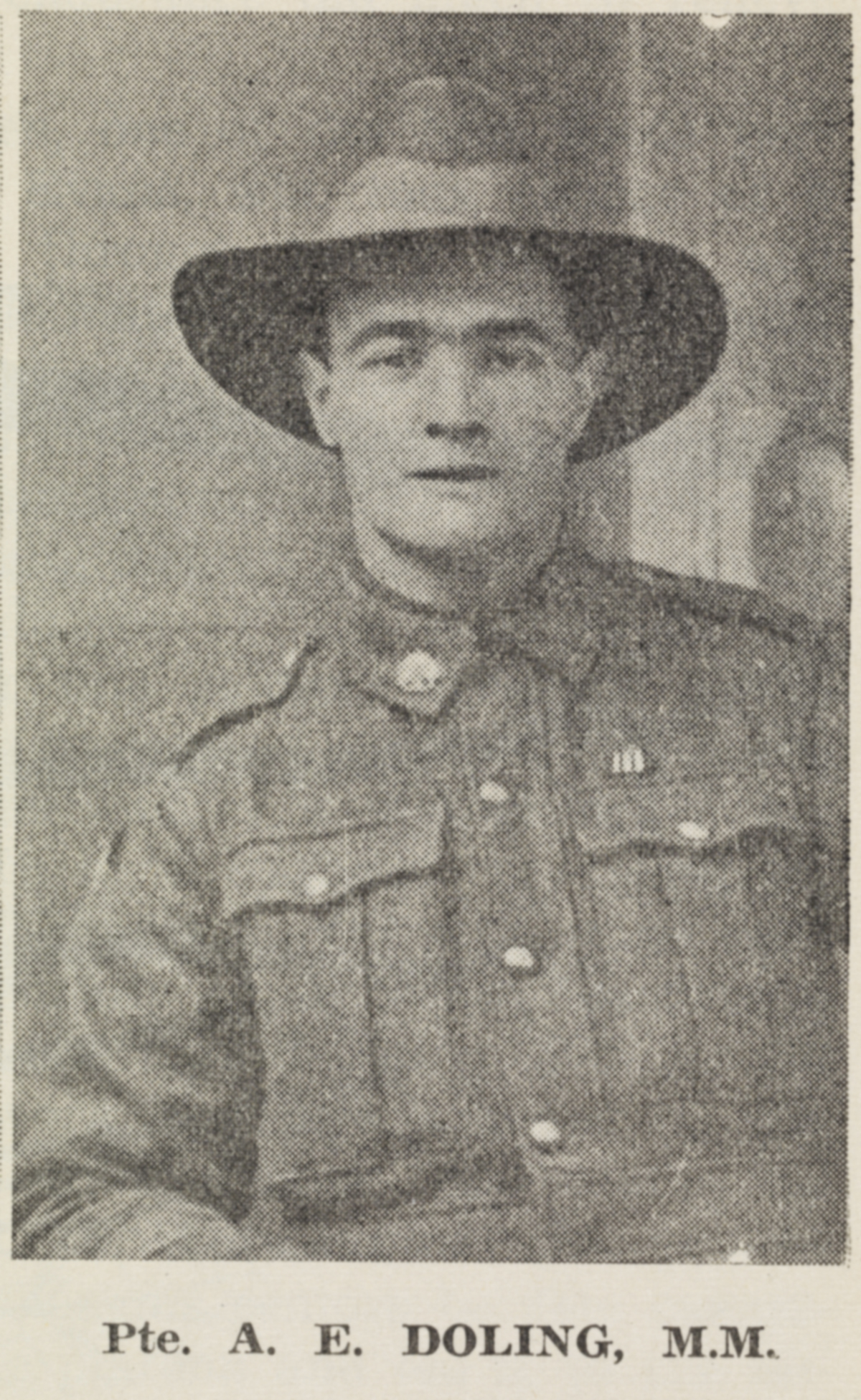

[media]One of 12 children, Albert Edward Doling lived above his father's hairdressing and tobacconist saloon at 636 Harris Street, Ultimo when he enlisted. [16] Doling served in the 17th Battalion in France and in April 1916 was reprimanded for disciplinary reasons and received 169 hours heavy labouring duties. Three months later, for behaving 'in an insolent manner' to a non-commissioned officer, he received 14 days' 'field punishment number one', which meant heavy labouring duties and being placed in fetters or handcuffs and attached to a fixed object for up to two hours a day. [17] According to family legend, Doling was punished because he objected to the 'inhumane treatment' of soldiers suffering from shell shock. [18]

On 9 November 1916, Doling was reported wounded in action. The following month he was punished while in Étaples, this time for 'hesitating to obey an order' and again given 14 days of field punishment number one. [19] In June 1917 he was found absent without leave (AWL) and awarded 14 days of field punishment number two (labouring duties), forfeiting 16 days' pay.

[media]Despite this track-record, Doling was awarded a Military Medal for 'unselfish devotion to duty' on 14 October 1917, excelled as a stretcher-bearer during the Battle of Menin Road, in the Third Battle of Ypres in Belgium. [20] According to the recommendation document:

During the operations on 20th September 1917…stretcher bearers worked consistently carrying and attending wounded for 24 hours, with little rest or food. [21]

Doling was sent to a hospital in Oxford in August 1918 after receiving a severe gunshot wound to his right thigh. According to family accounts, he was also wounded after jumping backwards into a trench when under fire and landing on the bayonet of a rifle borne by a soldier below. [22] On 13 December 1918 he married Emily Hazell, a 22-year-old nurse from Reading, and was found AWL again a few days later, probably with his new bride. He returned to Australia in April 1919. [23] Doling's family note that he was on a 'totally and permanently incapacitated' (TPI) pension after the war and suffered from severe insomnia and digestive problems as a result of being exposed to gas warfare. [24]

The disobedient clerk

James Fraser Harvie, a clerk living at 79 William Henry Street, Ultimo, was one of many boys who lied about their age in order to enlist in the AIF. [25] At 17 years old Harvie enlisted in the A Company of the 20th Battalion, arriving in Gallipoli in August 1915. In a letter dated 18 March 1967, he notes he was at Russell's Top, the highest point of Walker's Ridge. His battalion had arrived at Anzac Cove to defend Russell's Top just as the costly August Offensive was coming to an end. [26]

After the evacuation from Gallipoli, Harvie was sent to Alexandria in January 1916. His service record contains an extensive list of instances of misbehaviour. In February 1916 he received 21 days detention, reduced to 168 hours of 'field punishment number two', for being AWL in Tel-el-Kebir. He was then was transferred to the Imperial Camel Corps and the following month was made temporary lance corporal. From October to December 1916 he was in and out of hospitals in Egypt with 'septic sores' and later he was operated on for appendicitis. He was admitted to hospital in Cairo in August 1917 suffering from venereal disease and in September he was reprimanded for 'failing to salute an officer', forfeiting one day's pay. [27]

In November 1917 Harvie was found 'out of bounds in a brothel' in Wagh El-Birket, the red light district in Cairo. Having been absent from 9:30pm on 19 November until 12:30am on 20 November he was charged with 'breaking arrest'. He was found AWL again in February 1918 and was detained and sentenced to ten days' field punishment. In June 1918 he received a further 14 days' field punishment and forfeited one day's pay for AWL. The next month Harvie was attached to the 12th Light Horse Regiment and then to the 1st Anzac Battalion of the Imperial Camel Corps. He was repatriated in September 1919. [28]

The son of the reverend

It is perhaps unsurprising that Ian Muir, son of the Reverend Muir, outspoken and staunch supporter of the war, enlisted in the AIF bearing a letter of consent from his father. [29] Just shy of 18 years old, Ian Muir was technically underage. Despite this, he went on to have a distinguished war service which no doubt did his father proud.

Muir [media]served at Gallipoli in November 1915 before the Anzacs were evacuated to Alexandria in December. He was transferred to the 14th Machine Gun Company in March 1916, sailing for France three months later. In January 1917 he was appointed lance corporal but two months later was found guilty of 'hesitating to obey' an order given by an officer and was temporarily reduced in rank. In May Lance-Corporal Muir was admitted to hospital in Étaples with a sprain to his left knee and transferred to England, just after Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig mentioned him in despatches. [30] Brigadier General CJ Hobkirk had recommended Muir on 9 March 1917 and it was signed off by Talbot Hobbs, Major General Commanding the 5th Australian Division. The recommendation read:

Whilst on duty…[Muir] saw an enemy aeroplane, flying low, firing along our front line. He instantly converted his machine gun into an anti-aircraft position and engaged the aeroplane with such good effect that it was driven off and was observed to volplane to earth immediately behind the enemy lines. The following day an enemy aeroplane flew along the Sunion road, passing through the support line…firing a machine gun. Whilst under the fire of the gun Private Muir succeeded in mounting his gun and drove off the aeroplane. In both cases he showed considerable initiative and skill. [31]

After recuperating Muir attended the officer cadet school in Oxford where he was reported in March 1918 to be a 'good worker...intelligent, cheerful and receptive' with qualifications in anti-gas and machine gun. He was commissioned with the rank of lieutenant in August 1918 and returned to France. He returned to Australia after demobilisation and later graduated from Sydney University with a Bachelor of Dental Surgery. [32]

The missing pieces

This research into the Ultimo Presbyterian Church honour roll has raised many unanswered questions. With the gradual digitisation of archives such as the National Archives of Australia's repatriation records, and as new information comes to light more generally, we may be able to piece together the missing details of other soldier's stories with aspects that are absent from their service records. The stories of the war service of the men discussed here merely scratch the surface of a much bigger picture. We may yet discover what life was like for the men who returned to Sydney, with their traumatic memories and broken bodies, to find their names inscribed on a wooden board in a small church in Ultimo. As Monash University historian Professor Bruce Scates has remarked, these men were a 'war-wrecked generation' and their 'battles didn't end in 1918'. [33]

Further Reading

KS Inglis. Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape. 3rd ed. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2008.

Bruce Scates. 'Annual History Lecture 2015 – Anzac Amnesia: How the Centenary Forgot the War'. 8 September 2015. History Council of New South Wales. http://www.historycouncilnsw.org.au/history/post/annual-history-lecture-2015-anzac-amnesia-how-the-centenary-forgot-the-war/

Notes

[1] National Archives of Australia: B2455, Carlisle WT and NSW Births Deaths and Marriages, Registration no 1093/1899; National Archives of Australia: B2455, Newling Arthur Sidney and NSW Births Deaths and Marriages, Registration number 9092/1899

[2] State Records Authority of New South Wales, New South Wales Government Police Gazettes, Reference no 2107, 28 November 1912, 487, Series 10958, Reels 3129–3143, 3594–3606. See also National Archives of Australia: B2455, Chapple RC and B2455, Chapple RA

[3] National Archives of Australia: B2455, McPhee NC

[4] National Archives of Australia: B2455, Trott David and 1901 Scotland Census, Parish: Govan, ED: 31, page 19, Line 12, Roll: CSSCT1901_328

[5] National Archives of Australia: B2455, Trott David

[6] 'The Week,' 21 February 1918, Table Talk, 4, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article146645599, viewed 20 September 2015

[7] Correspondence with Trudy Holdsworth, 25 September 2015

[8] National Archives of Australia: B2455, Oldham Militan; State Records Authority of New South Wales, Registers of seamen engaged before the Shipping Master, 1859–1923, NRS 13282, reels 3669–3680

[9] Bruce Scates, 'Annual History Lecture 2015 - Anzac Amnesia: How the Centenary Forgot the War,' 8 September 2015, History Council of New South Wales, http://www.historycouncilnsw.org.au/history/post/annual-history-lecture-2015-anzac-amnesia-how-the-centenary-forgot-the-war/, viewed 30 September 2015

[10] National Archives of Australia: B2455, Carlisle WT and NSW Births Deaths and Marriages, Registration no. 1093/1899. Their surname was also spelt Carlyle. Carlisle's parents were William Henry and Flora Carlisle née McDermid. See also 'Enlistment standards,' Australian War Memorial https://www.awm.gov.au/encyclopedia/enlistment/, viewed 20 September 2015

[11] 'Mrs. Carlisle, of Ultimo, and Her Five Fighting Sons,' Sunday Times, 4 March 1917, 9, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article122797003, viewed 20 September 2015

[12] 'Responded To The Call Of Duty,' Sydney Mail, 19 September 1917, 24, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article160629931, viewed 20 September 2015

[13] National Archives of Australia: B2455, Carlisle WT

[14] National Archives of Australia: B2455, Carlisle WT

[15] National Archives of Australia: B2455, Carlisle WT

[16] NSW Births Deaths and Marriages, Registration no. 9065/1897

[17] National Archives of Australia: B2455, Doling AE. See also 'Field punishment,' Australian War Memorial https://www.awm.gov.au/encyclopedia/field_punishment/, viewed 20 September 2015

[18] Correspondence with Elaine Doling, 11 August 2015. See also 'Doling, Albert Edward,' Anzacs online, 23 November 2011, http://anzacsonline.net.au/2011/11/doling-albert-edward-mm/, viewed 20 September 2015

[19] National Archives of Australia: B2455, Doling AE

[20] National Archives of Australia: B2455, Doling AE; 'Albert Edward Doling,' Honours and Awards, Australian War Memorial https://www.awm.gov.au/people/rolls/R1519580/, viewed 20 September 2015; '2132 Pte AE Doling, Inf,' London Gazette, 12 December 1917, page 13025, position 13 https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/30424/supplement/13025/data.htm, viewed 20 September 2015. See also 'Battle of Menin Road,' Australian War Memorial, https://www.awm.gov.au/military-event/E97/, viewed 20 September 2015

[21] 'Albert Edward Doling,' Honours and Awards, Australian War Memorial https://www.awm.gov.au/people/rolls/R1519580/, viewed 20 September 2015

[22] Correspondence with Elaine Doling, 11 August 2015

[23] National Archives of Australia: B2455, Doling AE

[24] Correspondence with Elaine Doling, 11 August 2015

[25] NSW Births Deaths and Marriages, Registration number 28166/1897 and National Archives of Australia: B2455, Harvie JF

[26] '20th Australian Infantry Battalion,' Australian War Memorial, https://www.awm.gov.au/unit/U51460, viewed 20 September 2015

[27] National Archives of Australia: B2455, Harvie JF

[28] National Archives of Australia: B2455, Harvie JF

[29] National Archives of Australia: B2455, Muir Ian Miller and Victoria, Australia, Assisted and Unassisted Passenger Lists, 1839–1923, Microfiche VPRS 7666, copy of VRPS 947, Public Record Office Victoria

[30] National Archives of Australia: B2455, Muir Ian Miller; 'Ian Miller Muir,' Honours and Awards, Australian War Memorial https://www.awm.gov.au/people/rolls/R1531921; 'Supplement to the London Gazette,' London Gazette, 1 June 1917, page 5423, position 66 https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/30107, viewed 8 October 2015

[31] 'Ian Millers Muir,' Honours and Awards, Australian War Memorial https://www.awm.gov.au/people/rolls/R1624604, viewed 20 September 2015

[32] Sydney University, Book of Remembrance Entry, Ian Miller Muir, http://beyond1914.sydney.edu.au/profile/3681/ian-miller-muir, viewed 30 September 2015

[33] Bruce Scates, 'Annual History Lecture 2015 - Anzac Amnesia: How the Centenary Forgot the War,' 8 September 2015, History Council of New South Wales, http://www.historycouncilnsw.org.au/history/post/annual-history-lecture-2015-anzac-amnesia-how-the-centenary-forgot-the-war/, viewed 30 September 2015

.