The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Servicing Sydney's thirst

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The Cooks River and its role in water supply and sewerage

Despite the Cooks River flowing into Botany Bay, Captain Arthur Phillip of the First Fleet did not deem the area to be a suitable place for his new settlement and after several days sailed further around the coast before founding Sydney. That choice set the tone for the future use of Botany Bay and the Cooks River and saw the area develop very slowly through the nineteenth century; a hinterland of Sydney, suitable for the drawing of drinking water and later for the discharge of waste and the development of noxious industries. Despite the mouth of the Cooks River being barely more than 10 kilometres from Sydney Cove, the area was largely undeveloped by the mid nineteenth century, making it a suitable place for a thirsty city to go looking for a supplemental source of fresh water.

Early uses of the Cooks River

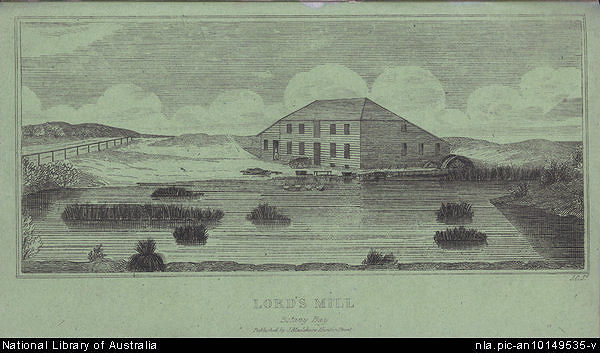

[media]While there had been some small-scale industry along the waterways leading into the Cooks River, particularly Simeon Lord's woollen mill from 1815 and a paper mill from 1818 [1], these industries seem not to have been so intensive in their use of water power or their discharge of waste to preclude the identification of the Botany Swamps as a suitable location to source water for central Sydney.

[media]The Cooks River area near Botany Bay remained sparsely settled throughout the early nineteenth century, the major development along the river being the dam for Lord's mill, built about 1820. The area along the river appears to have been a popular place for limekilns due to the presence of large numbers of shell middens left by the Aboriginal inhabitants of the area. This lime was burnt and transported back to Sydney for use in mortar. [media]Though too far away from the main settled areas to be viable commercially, it is also likely the river was used for fishing and other domestic purposes by the small number of local residents in this early period. Various species of edible plants were noted in the Botany Swamps area from early settlement, no doubt already in use by Aboriginal people who were also observed fishing in the Cooks River as late as the 1830s. [2]

The ever expanding demand for water

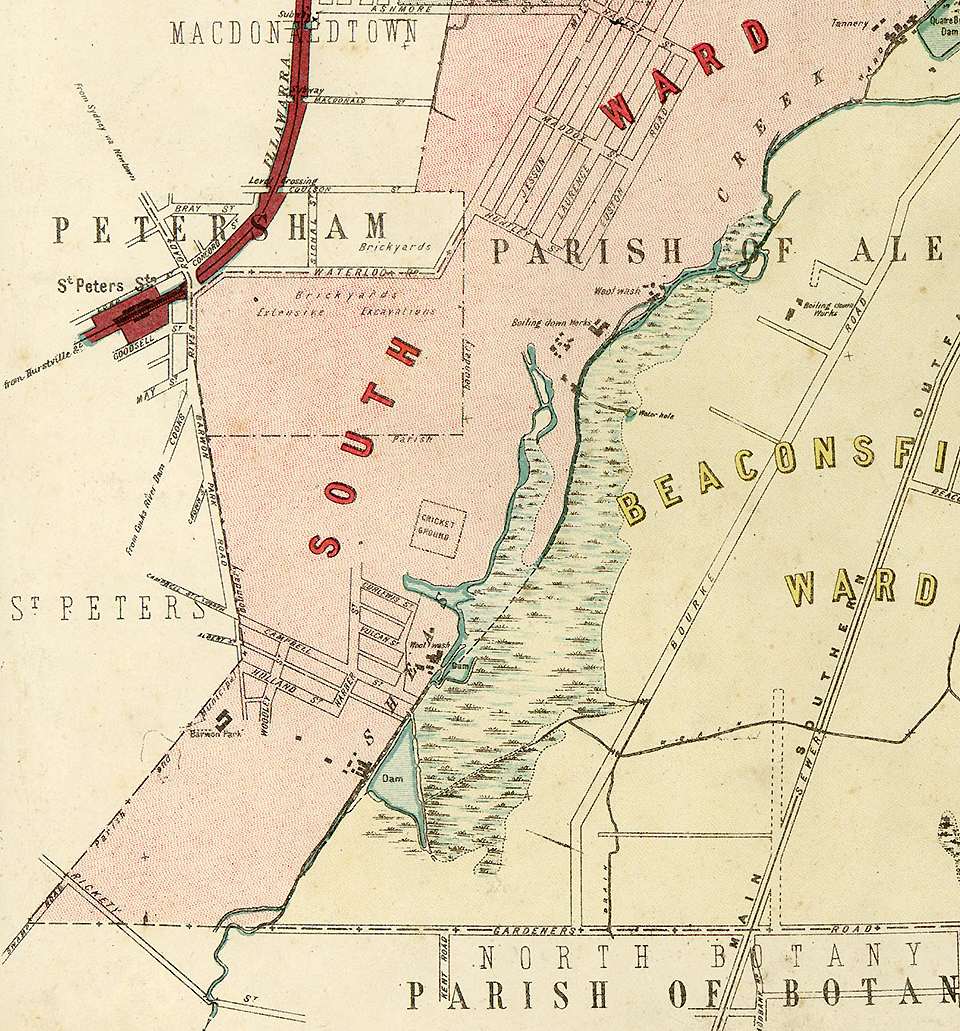

The Cooks River is fed by two major and one minor tributaries – Sheas Creek to the north (now Alexandra Canal), Wolli Creek to the west and Muddy Creek to the south. While all still exist, they are now highly modified with channels and serve an important ongoing role in the draining of stormwater. These tributaries drained much of what is now highly urban inner western Sydney, however, in the mid nineteenth century these areas were only lightly developed. While the Slaughter House Act of 1849 pushed many of the noxious industries out of inner city areas such as Ultimo to the city fringes and water courses leading to the Cooks River, by the 1850s the water supply situation for Sydney was dire enough to require the supplementing of the city's water supply by pumping from the Botany Swamps, along the Cooks River, despite the encroachments of industry.

[media]A major drought in the 1840s saw the relatively new Municipal Council of Sydney establish a special committee in 1850 to examine the improvement of the water supply. By 1852 a board had been appointed to review the suitability of the Botany Swamps for this purpose. The city commissioners took control of the management of the city and its infrastructure in 1854 and were responsible for implementing the Botany Swamps Scheme. Numerous resumptions were required in the area due to the existence of earlier land grants, including the resumption of 75 acres (30.4 hectares) of Simeon Lord's grant, incorporating the area of the mill, the dam which supplied it and Lord's residence. [3] The scheme did not come into operation until 1858 when the Botany Water Pumping Station came into service. Pumping commenced on 17 November 1858. The scheme was not transferred to the Metropolitan Board of Water Supply and Sewerage until 1888.

The Botany Water Pumping Station and the Botany Swamps Scheme

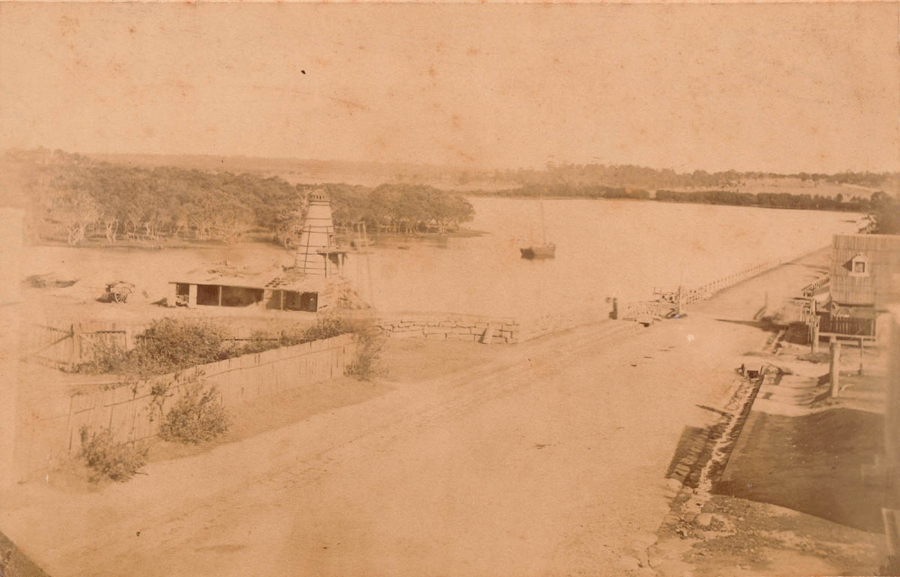

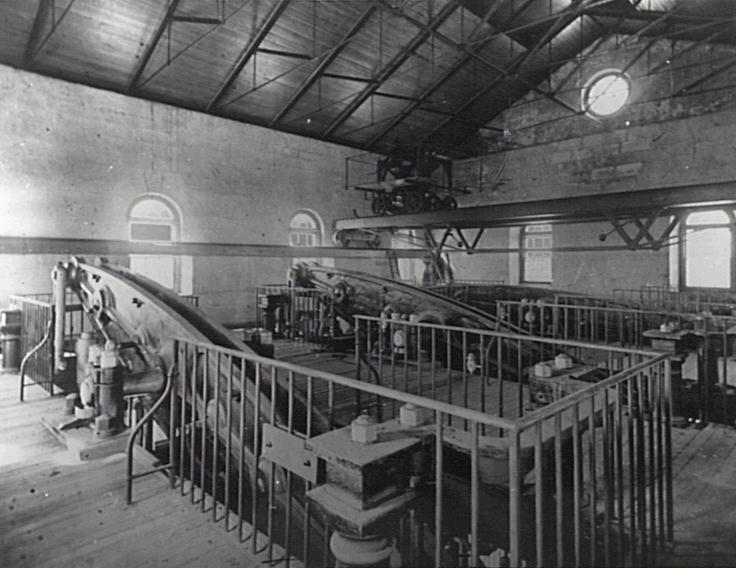

[media]The Botany Water Pumping Station was built over 1857–58. It was originally driven by three 100 horsepower low-pressure condensing steam engines [4] and drew water from the pond initially established for Lord's woollen mill and known as the Engine Pond. [5] The increased demand for water, as reticulation spread throughout the inner city, saw six additional dams constructed to service the Botany Swamps Scheme. However, another drought in the 1860s gave impetus to finding a more permanent and reliable water source for the city, [6] which saw the scheme rendered redundant within 30 years. The system of dams was also rather unreliable and some dams burst in heavy rains in 1867 and 1868. [7]

[media]The pumping station sent water through a 30 inch (76 cm) cast iron rising main to Crown Street Reservoir in Surry Hills (built 1854) and later to Paddington Reservoir on Oxford Street (built 1864). The filling of Paddington Reservoir was monitored by a staff member at the pumping station watching a stand pipe near Victoria Barracks through a telescope; when that stand pipe overflowed, that indicated Paddington Reservoir was full and pumping ceased. [8] Prior to the completion of these reservoirs, water storage was held within the mains only, leading to problems with the reliability of the supply and water to residents was shut off at night. [9] Remedial work was undertaken in 1872 in Busby's Bore, the second water supply, to improve its flows, which temporarily reduced the demand on the scheme. [10] Further work was done to supplement the scheme, through the installation of a pumping station at Crown Street Reservoir in 1875, the construction of the Bunnerong Dam in 1877 and the expansion of Paddington Reservoir in 1878. [11]

[media]The Botany Swamps Scheme continued to act as Sydney's third water supply until the Upper Nepean Scheme came into operation in 1886. The change in the quality of the water from the Botany to Upper Nepean Schemes was noted in the board's annual report of 1889: 'Chemically this water is very pure and far in advance of the old Botany supply.' [12] The pumping station was kept in service for backup purposes until 1893:

The Botany pumps were worked under steam several days on two different occasions in the early part of the year, and were turned round, each engine respectively, every week by hand. A boiler-fire has been kept banked during the whole time, and the banking changed periodically for the purpose of drying flues and keeping the external bottom of boilers dry. [13]

[media]Following the closure of the waterworks, the area around the pumping station was let out for woolwashing, with water drawn from the former Engine Pond. [14] The plant was finally dismantled in 1896 [15], with the equipment relocated to Hay and the chimney stack incorporated into the Southern and Western Suburbs Ocean Outfall Sewer (SWSOOS) to vent sewer gas. The remnants of the pumping station's foundations and the stub end of the chimney stack still exist, in a rather forlorn state, within the grounds of Sydney Airport.

The Botany Swamps [media]were progressively consumed by the development of industry around Botany Bay; however elements of the swamps (now referred to as the Botany Water Reserve) survive as Eastlakes and The Lakes golf courses. In addition to their recreational function, these areas continue to serve an important role in stormwater drainage. Much of the rest of the swamps was consumed by the expansion of Kingford Smith (now Sydney) Airport, first in 1948 [16] and again in 1970. These expansions also necessitated the diversion of the lower reaches of the Cooks River from its original course.

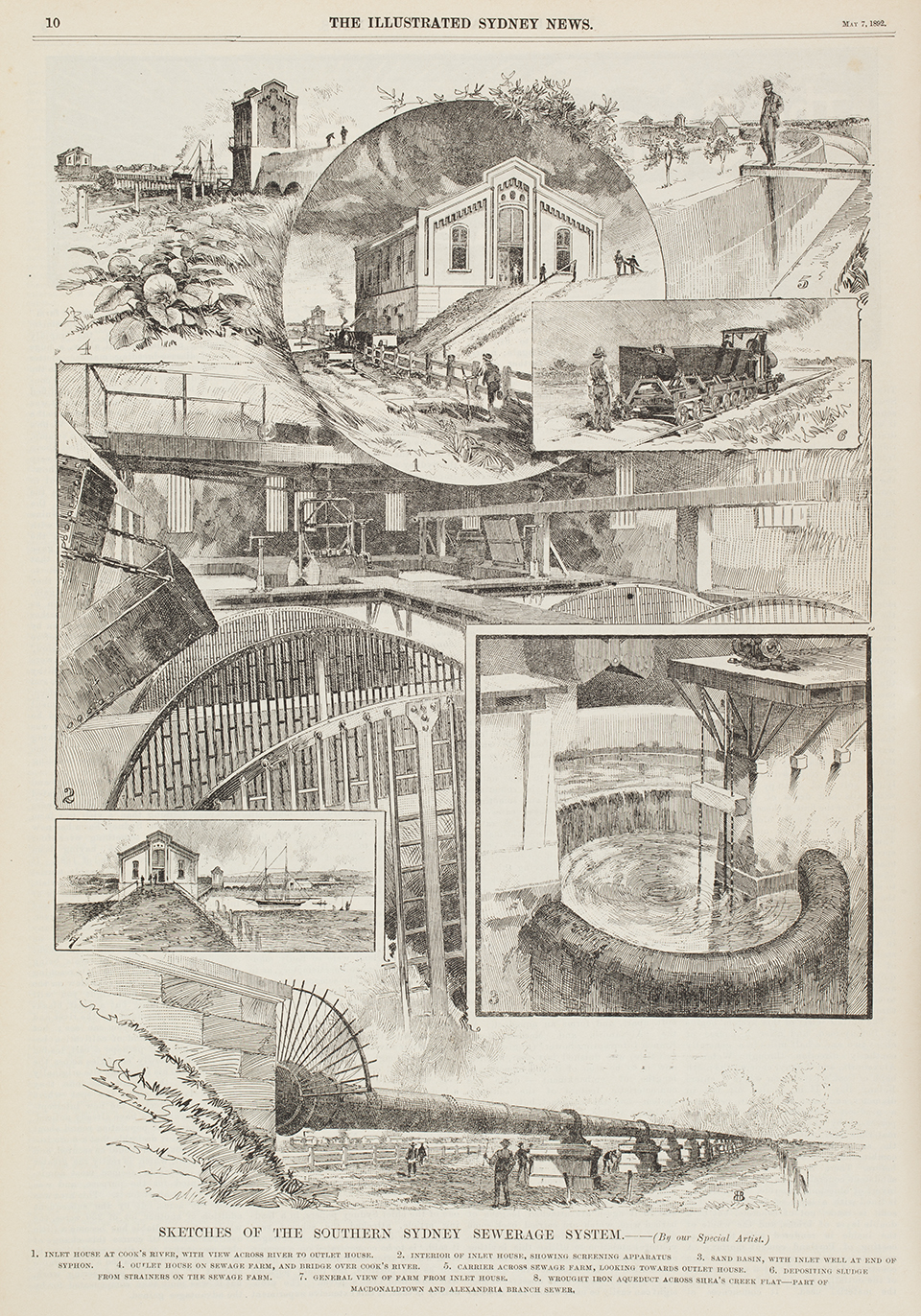

Botany Sewage Farm

[media]Prior to 1877, Sydney had a 'combined' sewer and stormwater system, that is, the same pipes and channels were used to dispose of stormwater as well as wastewater, generally directly to the harbour or other nearby watercourses. This had a considerable impact upon public health, as well as being a system liable to back up and overflow in times of high rainfall. From 1877 there was a progressive change for both practical and public health reasons to a 'separated' system for stormwater and wastewater. In 1882, 309 acres (125 hectares) of land known as Webb's Grant near the mouth of the Cooks River was resumed for the establishment of a sewage farm [17] as well as 311 acres (126 hectares) along Muddy Creek. [18] From that time, the wastewater from the central and southern areas of Sydney was discharged at the Botany Sewage Farm at Kyeemagh, on the southern side of the Cooks River. [19] Night soil was also collected and carted to the farm from throughout Sydney, a source of irritation and resentment to local residents. [20]

[media]The sewage farm was a series of large fields where sewage was laid out in filtration drains with the sandy soil filtering the effluent as it made its way into the Cooks River. Some of the soil was used to fertilise the nearby market gardens which had operated in the Botany Bay area since the 1830s. [21] Sewage was initially screened on the northern bank of the Cooks River before being dosed with lime and loaded into tip trucks attached to a small steam locomotive. This locomotive ran across a wooden bridge over the Cooks River and dumped the screened waste into the filtration beds. In 1903, the bridge was replaced with a syphon running along the river bed pushed by compressed air from the north side of the river to an outlet house on the south side.

Ongoing complaints from neighbours saw various early attempts at sewage treatment trialled at the farm, with only limited success. [22] The use of the farm for the production of vegetables and pigs was tried throughout its period of operation but again with only limited success. Public health concerns led to the cessation of pig farming in 1905 and by 1908 there was very limited market gardening happening on the farm itself. The Botany Sewage Farm operated until 14 September 1916 when wastewater was diverted to the ocean outfalls along the coastline. Much of the area of the farm is now occupied by Kogarah Golf Course and Barton Park, near the mouth of the Cooks River.

Changing attitudes – recognising the problem of pollution

[media]Reticulated sewerage systems began to spread throughout Sydney and its suburbs in the late nineteenth century. The Cooks River and its tributaries were crossed by a number of sewage aqueducts, carrying waste for the newly constructed Western Main Sewer (now part of the SWSOOS). Decorative brick aqueducts, designed by the public works department, carried large cast-iron pipes across the Cooks River, Wolli Creek, Muddy Creek and Arncliffe. The decorative nature of these well-designed structures highlights the pride taken in civic infrastructure works at that time, when aesthetics was given as much thought as function. These aqueducts continue to serve as parts of the SWSOOS today.

By the early twentieth century, the Metropolitan Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board was pursuing a goal of having no sewage discharging into the harbour or the Cooks River, attempting rather to intercept and pump all wastewater into one of the ocean outfall sewers. [23] A network of small electrically-driven sewage pumping stations (SPSs) was built throughout inner western Sydney in the early twentieth century in pursuit of this goal, controlled by the Number 1 Sewage Pumping Station at Ultimo, on William Henry Street, directly opposite, and powered by, the Tramway Power Station. Many of these pumping stations are still in operation and serve the same purpose – the pumping of wastewater out of low-lying areas and into mains leading to the outfalls – to prevent sewage overflows into the Cooks River and other watercourses.

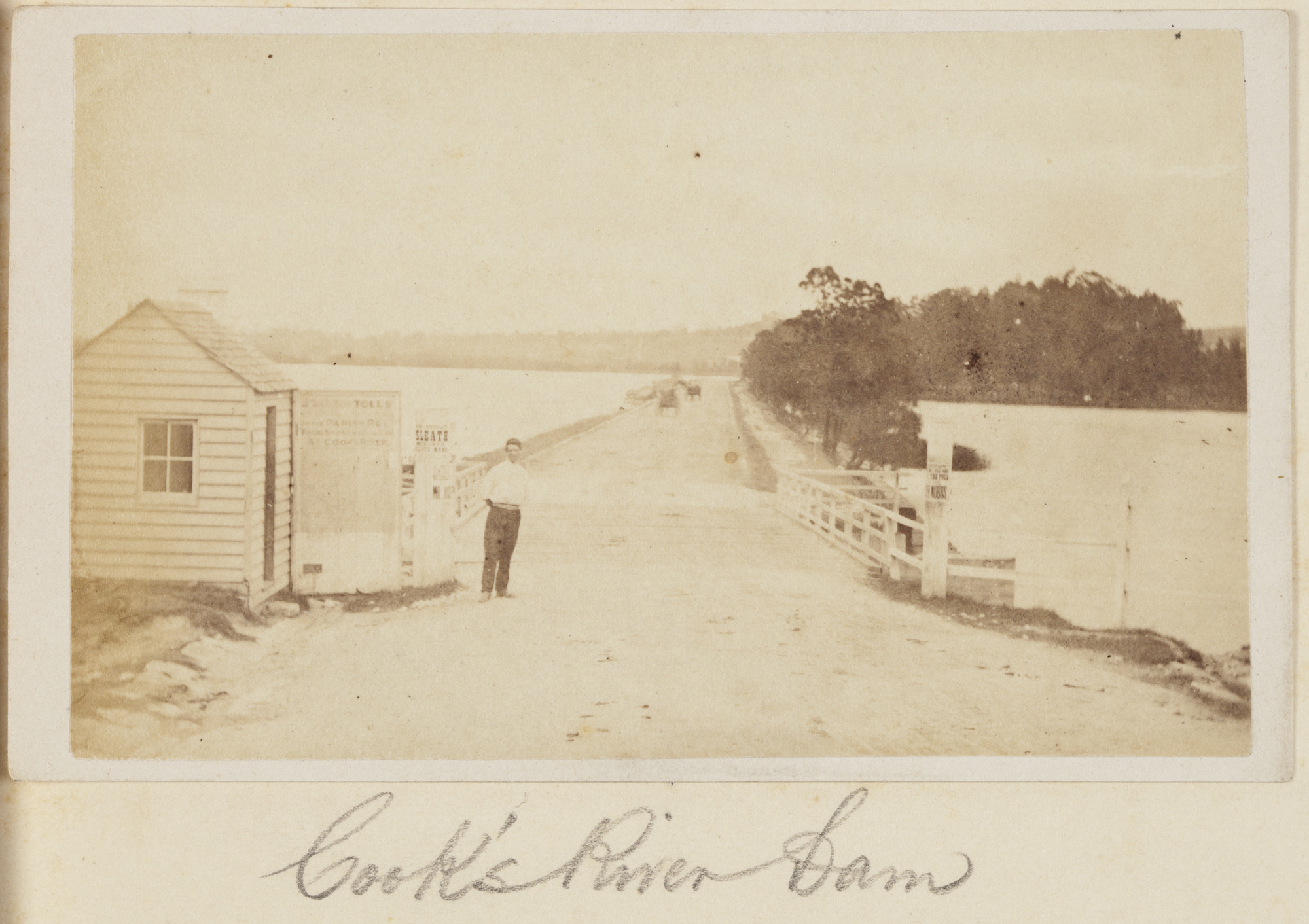

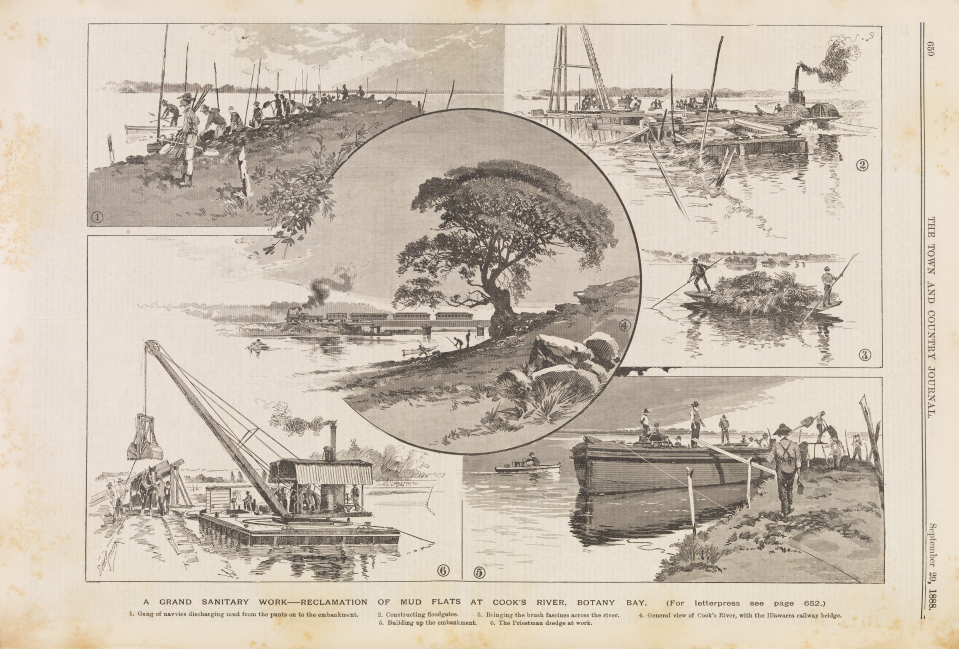

[media]As the nineteenth century wore on, the Cooks River became an even greater sink for the city's pollution, the Botany Swamps and Cooks River going the way of the Tank Stream many years before. The establishment of a dam across the river near Tempe in 1840 was one of the first impositions on the river. [media]By the 1840s, many noxious trades had relocated to Sheas Creek, with industries such as tanneries dumping chemical and industrial wastes into this tributary of the Cooks River. [24] Sheas Creek was itself channelled to become the Alexandra Canal between 1894 and 1896, in an overambitious plan to establish a shipping connection to the Parramatta River, which never eventuated. [media]Rather, the canal merely became a vast sewer for industrial waste dumped directly into the water or washed in during rains from the surrounding areas. Coupled with the sewage farm on the south bank of the river, the Cooks River had become highly polluted by the late nineteenth century. In that regard, it is fortunate that the Upper Nepean Scheme came into service in 1888, providing an alternative to the Botany Swamps Scheme before the pollution had destroyed yet another source of Sydney's potable water.

[media]As development spread along the Cooks River, the other watercourses feeding into it were themselves progressively channelled. Wolli Creek, Muddy Creek and the upper reaches of the Cooks River itself all had their banks replaced with concrete to improve the efficiency of their drainage. This had the effect of vastly improving the surrounding areas as suitable locations for residential and commercial development; however, there were severe consequences for the river in terms of pollution and siltation. While the sorts of noxious industries that once fed into the river no longer operate and the management of domestic and trade wastes has vastly improved, the Cooks River continues to collect silt and pollution for surface runoff along its length.

Contemporary role of the Cooks River in Sydney's water supply

The Cooks River no longer serves as a source of fresh water or foodstuffs, however, it also no longer serves as a place to dump the bulk of the city's waste. Efforts commencing in the late nineteenth century and continuing through to today have progressively reduced these impacts on the river. Despite this, it is still far from its pristine state of the late eighteenth century when Phillip determined that Botany Bay was not suitable for the founding of Sydney. The river continues to be affected by urban runoff and siltation but far less from direct discharge. Various attempts have been made to beautify and naturalise elements of the river and establish recreational areas along parts of its banks, however, it remains a highly modified and constructed watercourse. In addition to this recreational role, the river continues to serve an important function in the draining of stormwater from the surrounding low-lying suburbs.

References

WV Aird, The Water Supply, Sewerage and Drainage of Sydney, NSW Metropolitan Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board, Sydney, 1961

M Beasley, The Sweat of Their Brows: 100 Years of The Sydney Water Board, 1888–1988, Sydney Water Board, Sydney, 1988

FJJ Henry, The Water Supply and Sewerage of Sydney: Being an Account of the Development and History of the Water Supply and Sewerage Systems of Sydney and the South Coast From Their Inception to the End of the First 50 years of Control by a Board Specially Constituted for the Purpose, NSW Metropolitan Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board & Halstead Press, Sydney, 1939

James Jervis and Leo R Flack, A Jubilee History of the Municipality of Botany 1888–1938, Botany Municipal Council, Botony, NSW, 1938

FA Larcombe, The History of Botany 1788–1970, second edition, The Council of the Municipality of Botany, Sydney, 1970

TJ Roseby, Sydney's Water Supply and Sewerage 1788 to 1918: Opening New Offices, WA Gullick, Government printer, Sydney, 1918

St George Historical Society, A Century of Progress: Rockdale 1871–1971, St George Historical Society, Rockdale, 1971

Notes

[1] James Jervis and Leo R Flack, A Jubilee History of the Municipality of Botany 1888–1938, Botany Municipal Council, Botony, NSW, 1938, pp 52–58

[2] Val Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigating the Archaeological and Historical Records, second edition, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2010, pp 41, 84

[3] FA Larcombe, The History of Botany 1788–1970, second edition, The Council of the Municipality of Botany, Botony, Sydney, 1970, pp 97–99

[4] TJ Roseby, Sydney's Water Supply and Sewerage 1788 to 1918: Opening New Offices, WA Gullick, Government printer, Sydney, 1918, pp 23, 40–41

[5] FJJ Henry, The Water Supply and Sewerage of Sydney: Being an Account of the Development and History of the Water Supply and Sewerage Systems of Sydney and the South Coast From Their Inception to the End of the First 50 years of Control by a Board Specially Constituted for the Purpose, NSW Metropolitan Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board & Halstead Press, Sydney, 1939, pp 48–51; see also M Beasley, The Sweat of Their Brows: 100 Years of The Sydney Water Board, 1888–1988, Sydney Water Board, Sydney, 1988, pp 7–8

[6] FA Larcombe, The History of Botany 1788–1970, second edition, The Council of the Municipality of Botany, Botony, NSW, 1970, pp 98–99; see also FA Larcombe, 'The Stabilisation of Local Government in New South Wales 1858–1906', A History of Local Government in New South Wales, vol 2, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 1976, pp 88–91

[7] FJJ Henry, The Water Supply and Sewerage of Sydney: Being an Account of the Development and History of the Water Supply and Sewerage Systems of Sydney and the South Coast From Their Inception to the End of the First 50 years of Control by a Board Specially Constituted for the Purpose, NSW Metropolitan Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board and Halstead Press, Sydney, 1939

[8] NSW Metropolitan Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board, Official Handbook, 1913, second edition, Sydney, 1913, pp 14–15

[9] NJ Thorpe, 'The History of the Botany Water Supply', The Sydney Water Board Journal, vol 3, no 3, 1953, p 76

[10] WV Aird, The Water Supply, Sewerage and Drainage of Sydney, NSW Metropolitan Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board, Sydney, 1961, pp 6–7

[11] WV Aird, The Water Supply, Sewerage and Drainage of Sydney, NSW Metropolitan Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board, Sydney, 1961, pp 12–14.

[12] New South Wales Metropolitan Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board, Annual Report, Sydney, 1889, p 2

[13] Required in April of that year as noted in New South Wales Metropolitan Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board, Annual Report, Sydney, 1889, pp 11, 14

[14] New South Wales Metropolitan Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board, Annual Report, 1895, Sydney, 1895, p 58

[15] 'The outbuildings are dilapidated, and require considerable repair before being of any use' quoted in Metropolitan Board of Water Supply and Sewerage, Annual Report, New South Wales Metropolitan Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board, Sydney, p 61

[16] WV Aird, The Water Supply, Sewerage and Drainage of Sydney, New South Wales Metropolitan Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board, Sydney, 1961, pp 197–199

[17] FA Larcombe, The History of Botany 1788–1970, second edition, The Council of the Municipality of Botany, Botony, NSW, 1970, pp 100–101

[18] St George Historical Society, A Century of Progress: Rockdale 1871–1971, St George Historical Society, Rockdale, 1971, p 16

[19] New South Wales Metropolitan Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board, Official Handbook, second edition, Sydney, 1913, pp 91–92

[20] St George Historical Society, A Century of Progress: Rockdale 1871–1971, St George Historical Society, Rockdale, 1971, p 16

[21] James Jervis and Leo R Flack, A Jubilee History of the Municipality of Botany 1888–1938, Botany Municipal Council, Botony, NSW, 1938, pp 65–67

[22] FJJ Henry, The Water Supply and Sewerage of Sydney: Being an Account of the Development and History of the Water Supply and Sewerage Systems of Sydney and the South Coast From Their Inception to the End of the First 50 years of Control by a Board Specially Constituted for the Purpose, New South Wales Metropolitan Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board and Halstead Press, Sydney, 1939, pp 171–174

[23] FJJ Henry, The Water Supply and Sewerage of Sydney: Being an Account of the Development and History of the Water Supply and Sewerage Systems of Sydney and the South Coast From Their Inception to the End of the First 50 years of Control by a Board Specially Constituted for the Purpose, NSW Metropolitan Water, Sewerage and Drainage Board and Halstead Press, Sydney, 1939, pp 125–126

[24] Chrys Meader and Richard Cashman, Marrickville: Rural Outpost to Inner City, Hale & Iremonger, Petersham, NSW, 1990, pp 34–36

.