The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Darlinghurst courthouse

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Darlinghurst courthouse

By 1830 the existing courts in Sydney Town were overcrowded, hearing cases that were sometimes chaotic affairs, and with their public galleries packed with a vocal, restive crowd of spectators who could easily wander in from the surrounding streets. Governor Bourke, who arrived in the colony in 1831, instructed the Colonial Architect, Ambrose Hallen, to draw up designs for a new courthouse, to be built adjacent to the proposed gaol in Darlinghurst. This location would provide ready access to prisoners, and would also symbolically place the court on a ridge, high above the city.

Nothing eventuated from Hallen's Grecian-inspired plans, and when he was replaced by Mortimer Lewis in 1834, new plans were drawn up. What eventually became the Darlinghurst Court of General and Quarter Sessions appears to have been established by 1 February 1842, following a direction from the Governor

...that all future Quarter Sessions for the Town and District of Sydney, will be held in the New Court House, at Darlinghurst.

This Greek Revival building was the first purpose-built courthouse in New South Wales, and became the template for courthouse design throughout the colony for the next 60 years. The project also represented a major shift in the colony's approach to public works, for although convict labour was used to dig its foundations, most of the work was carried out by private contractors and sub-contractors. Indeed, this was partly the reason for the lengthy delays in completing the building, but gradually the sandstone edifice rose up, its pediment and pillars visible for miles around. It was a singularly impressive achievement, a building which manifested the colony's architectural design capabilities, and its 'really good and handsome masonry', but also symbolised the changing nature of its society. [1] If [media]the nearby gaol was a visual reminder to people of the wages of sin, then the considerably more elegant courthouse was a suitably monumental and 'classical' signal of the importance of the rule of law, and the colony's ability to administer justice and civil authority. [2]

The courthouse was aligned to face directly onto Oxford Street, and became the defining feature of the entire space on the top of Darlinghurst Hill. Even before it was finished, it had been used as a church by people living along the South Head Road. [3] It had also served as the venue for other community functions, such as the town's annual St Patrick's Ball, a 'gay and festive scene' attended by some 300 to 400 people in 1840. [4]

While the courthouse redefined the streetscape at Darlinghurst Hill, it also brought with it greater regulation of the street itself. For instance, one of the enduring problems in mid-nineteenth-century Sydney was the abundance of animals on the streets. All manner of beasts from goats to cows, and literally hundreds of dogs, could be seen even on the city's busiest streets. Along the South Head Road, cattle had for years wandered, seemingly at random, onto neighbouring land. This continued even after the courthouse was built, so that in the 1840s there were still cows grazing under the very pillars that were meant to denote law, order and authority. The irony of the lawyers and judges and the whole paraphernalia of the law – the wigs, gowns, leather-bound tomes – keeping such bovine company was no doubt appreciated by the lower orders, many of whom frequently found themselves before this very court. Eventually the matter was taken in hand by fencing off the courthouse in 1849 and imposing more stringent regulation of people who kept animals and used the road.

Twentieth-century changes

The Darlinghurst court has played a great part in Sydney's legal history, but also in Australia's legal history. From the establishment of the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901 until the 1920s, the High Court had no building of its own, and used existing courts in the various state capitals: in Sydney it used part of the Darlinghurst courthouse. But these facilities soon became inadequate as the workload and the standing of the High Court continued to rise, and the Commonwealth Government accepted the need to provide new buildings in Sydney. Additional space for newly appointed Justices of the High Court was provided by alterations and additions to the Darlinghurst District Court building in 1907, 1913, 1914, and 1921, but even so, in 1920, Chief Justice Sir Adrian Knox commented,

Until we get another court of our own it will be impossible to arrange the work to the best advantage.

New purpose- built accommodation was constructed for the High Court adjacent to the existing Darlinghurst District Court buildings. The new building was free-standing and constructed in stone to the west of the main court complex, from which it was separated by a small garden and a stone wall. Intended to blend in with the Grecian style of the original court buildings, it echoed many of the design and planning principles of the Lewis building, such as the central court space and the dominant entry facade.

The High Court building at Taylor Square opened in 1923, and over the years, many important cases were heard there, including sittings of the Royal Commission into Espionage of 1954. During this enquiry into the revelations of the Petrov affair, the Federal Opposition Leader, Dr HV Evatt, appeared as counsel for two of his staff members, AJ Dalziel and A Grundemann, who had been named as spies.

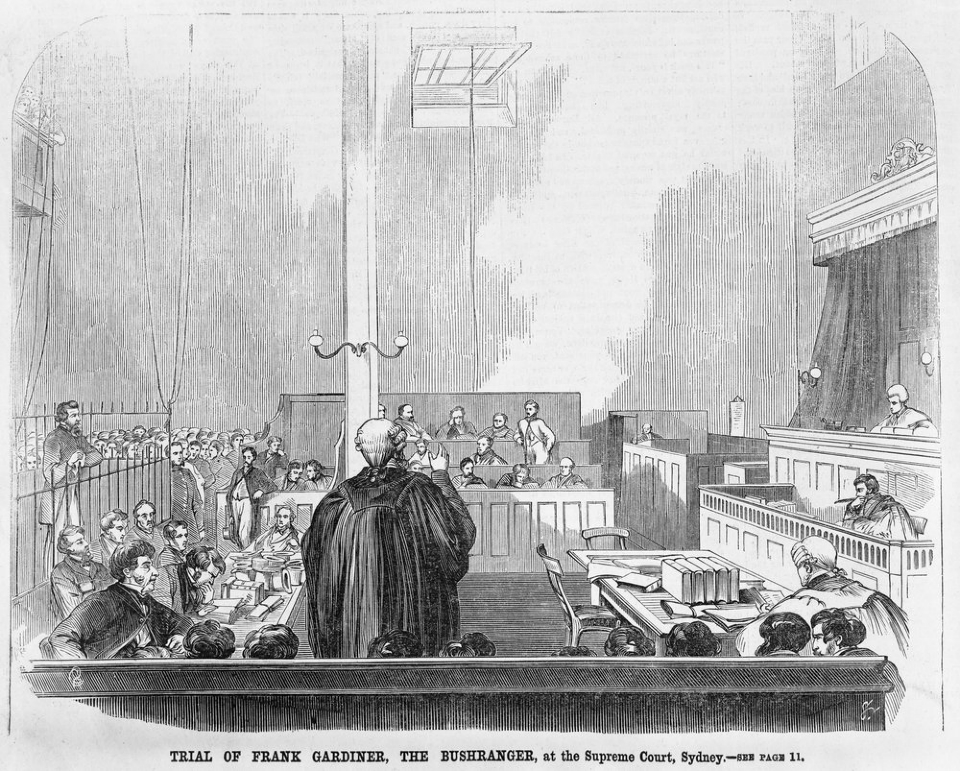

Many important and notorious criminal trials were heard in the Darlinghurst courthouse. Examples include the trial of Stephen Bradley for the murder of Graeme Thorne in 1961 and, more recently, the trial of Bruce Burrell, who was found guilty in June 2006 of kidnapping and murdering Sydney woman Kerry Whelan.

New South Wales's old court system ceased on 1 July 1973 when Courts of General and Quarter Sessions were abolished, and the district courts took on the criminal as well as the civil jurisdiction. Darlinghurst Court of General and Quarter Sessions became a court in the District Court Criminal and Special Jurisdiction, Sydney and Central Division.

The complex of sandstone buildings has great heritage value. [5] It contains three courtrooms, galleries, vestibules, offices, chambers, central portico and flanking colonnades: it has a slate roof, timber floors (marble inside vestibules) and cedar joinery. It has a Doric portico, elaborate pediment with coat of arms, and flanked colonnaded wings standing slightly forward.

References

JM Bennett, A history of the Supreme Court of New South Wales, Law Book Co, Sydney, 1974

Peter Bridges, Historic Court Houses of New South Wales, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1986

Clive Faro, Street Seen: A History of Oxford Street, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2000

'History of the High Court', High Court of Australia website, http://www.hcourt.gov.au/about_02.html, viewed 5 March 2009

Notes

[1] James Maclehose, Picture of Sydney and strangers' guide in New South Wales for 1839, John Ferguson in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society, Sydney, 1977, (first published 1839) pp 120–21

[2] Sydney Morning Herald, 8 February 1842; Peter Bridges, Historic Court Houses of New South Wales, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1986, pp 29–32; JM Bennett, A history of the Supreme Court of New South Wales, Law Book Co, Sydney, 1974, p 7; NSW Public Works Department, Darlinghurst Court House Conservation Plan, Sydney 1985

[3] 'Lyth', The golden south: memories of Australian home life from 1843 to 1888, Ward & Downey, London, 1890, p 82

[4] Australian, 19 March 1840

[5] J Broadbent, Colonial Greek: The Greek Revival in New South Wales, 1810–1850, Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales, Sydney, 1985