The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

McKenzie, Violet

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

McKenzie, (Florence) Violet

Florence Violet McKenzie [media]was Australia's first female electrical engineer. She set up her own electrical contracting business in 1918, and apprenticed herself to it, in order to meet the requirements of the Diploma in Electrical Engineering at Sydney Technical College. Her great enthusiasm was the new medium of radio, and in 1922 she was the first Australian woman to take out an amateur radio operator's license. Through the 1920s and 1930s, her Wireless Shop in the Royal Arcade - 'the oldest radio shop in town' [1] - was renowned amongst Sydney radio experimenters and hobbyists. There were other achievements: founding The Wireless Weekly in 1922, establishing the Electrical Association for Women in 1934, writing the first 'all-electric cookbook' in 1936, corresponding with Albert Einstein in the postwar years. But McKenzie is best known for her extraordinary voluntary effort during World War II. She established the Women's Emergency Signalling Corps in 1939, and campaigned successfully to have some of her female trainees accepted into the all-male Navy, thereby originating the Women's Royal Australian Naval Service. Meanwhile, some 12,000 servicemen passed through her signal instruction school at 10 Clarence Street, acquiring essential skills in Morse, visual signalling and international code. [2] While the training of servicemen was her war effort, technical training for women was her great ambition from the start.

Childhood and education

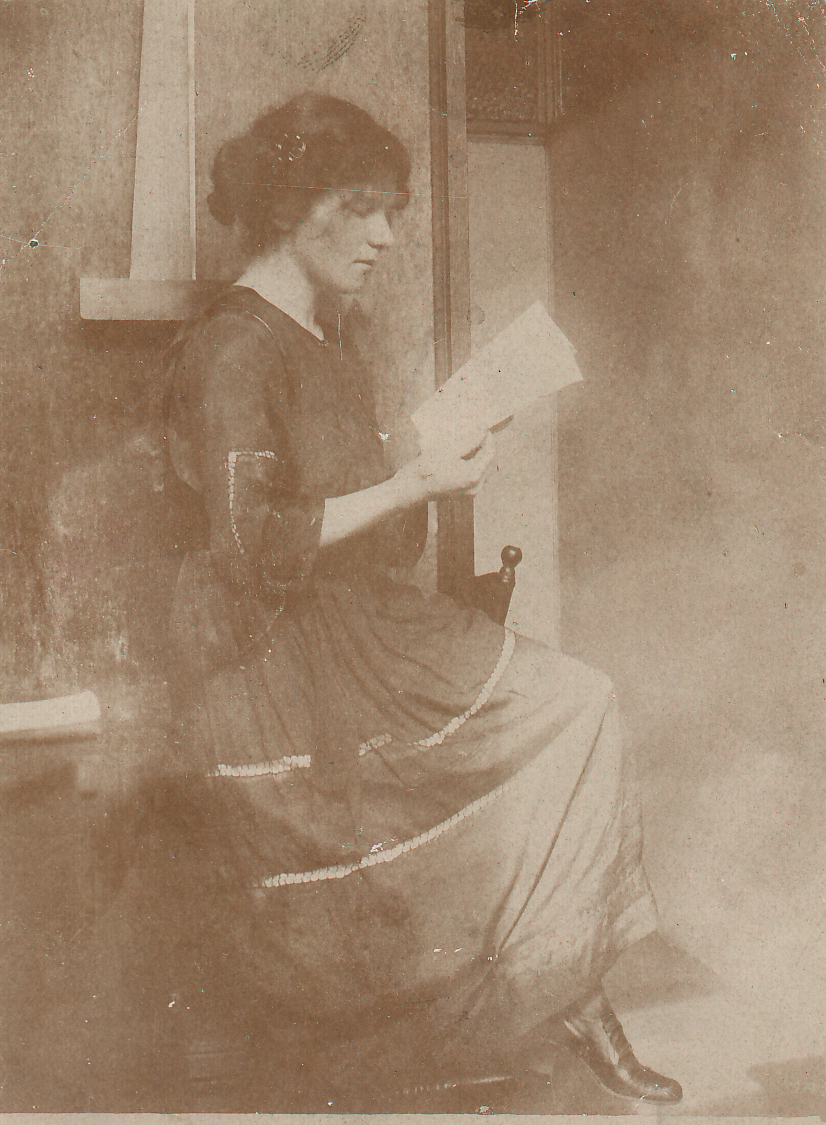

Before [media]her marriage to Cecil McKenzie at the age of 34, Florence Violet McKenzie was known as Violet Wallace, though she was born Florence Violet Granville, on 28 September 1890, in Melbourne. Wallace was her stepfather George's surname; he was a commercial traveller. When Violet was an infant, the family moved to Austinmer, south of Sydney.

From a young age, Violet had an independent interest in electricity and invention. As she recalled in an oral history interview in 1979:

I used to play about with bells and buzzers and things around the house. My mother would sometimes say 'Oh, come and help me find something, it's so dark in this cupboard' – she didn't have very good eyesight… So I'd get a battery and I'd hook a switch, and when she opened that cupboard door a light would come on… I started sort of playing with those things. [3]

From Thirroul school, Violet won a bursary to study at Sydney Girls' High School. In 1915 she passed Chemistry I and Geology I at the University of Sydney, [4] then approached the Sydney Technical College in Ultimo to enrol in the Diploma of Electrical Engineering. She later recounted the extraordinary story of persuading the College to let her in:

I went down to Technical College and saw the Head there, and he said, 'Oh, you can't come here and do engineering unless you're working at it'… I said, 'Well now, suppose I had an electrical engineering business and I'm working at it, would that be all right?' He said, 'Yes, if you produce proof.' So I went back and I had some cards printed with my name on, and electrical work, and got the paper and wrote down the ads, and read that a house… way out beyond Marrickville somewhere, was asking for prices for putting in electric light and power... I went out there and nobody else was silly enough to go, so they gave me the job. It was about a mile from the end of the tram line… I went back to Tech and took my card down and showed them the contract for the job, and they said, 'All right, you can start.' [5]

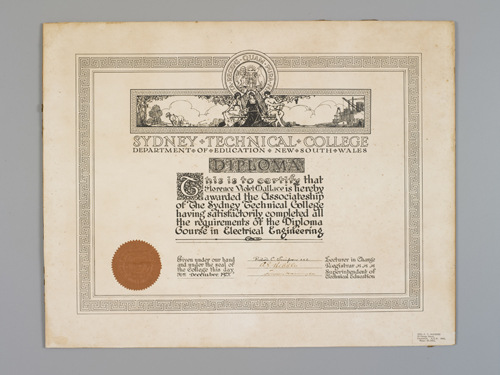

In December [media]1923, Florence Violet Wallace graduated from the Sydney Technical College. Her Diploma – the first of its kind awarded in Australia to a woman – is held in the collection of the Powerhouse Museum.

Electrical work, supplier of radio parts, publisher, experimenter

Throughout her [media]studies, Violet worked as an electrical contractor, installing electricity in private houses, such as that of politician Archdale Parkhill in Mosman, and in factories and commercial premises, including the Standard Steam Laundry on Dowling Street, Woolloomooloo. [6]

In 1922 Miss Wallace opened The Wireless Shop in the Royal Arcade. Ric Havyatt of the Historical Radio Society of Australia remembers visiting the shop during his [media]school days:

It was only a short walk across Hyde Park from Sydney Grammar School… The Arcade was home to several radio shops. Miss Wallace's was always crowded, and I seem to remember her occasionally helping out the penurious with second hand parts. [7]

McKenzie later said it was schoolboys visiting her shop who first introduced her to Morse code. [8]

Australia's first weekly radio magazine was conceived at Miss Wallace's Wireless Shop, by McKenzie and three co-founders. The Wireless Weekly eventually became Electronics Australia, and remained in circulation until 2001.

In 1924 McKenzie [media]became the only female member of the Wireless Institute of Australia. [9] That same year she travelled to the United States for business reasons, and in San Francisco was welcomed at radio 6KGO: 'Miss Wallace, an electrical engineer from Australia, will now talk from the studio.' She reportedly used her time on air to comment on the difference between the tram systems in San Francisco and those in Sydney. [10]

In 1931 McKenzie recorded in The Wireless Weekly that she experimented with television as well as radio:

Have a pronounced kink for television work and devote most of my spare time in experimenting that branch of the science. Have a deep-rooted conviction that chemistry is going to provide the solution and am working along those lines. [11]

Marriage

Cecil Roland McKenzie was a [media]young electrical engineer employed by the Sydney County Council's Electricity Undertaking. He too was a radio enthusiast, and one of Violet's customers. They were married at the Church of St Philip in Auburn on New Years Eve 1924. They built a house at 26 George Street, Greenwich, complete with a wireless room in the attic, [12] and an enormous fish pond in the front yard. [13] The house remains, but has been extensively renovated since the McKenzies lived there.

The McKenzies had a mutual interest in tropical fish. She spoke of heating water electrically to house tropical fish at home in the early 1920s, and of having given talks on radio 2FC about tropical fish in the days when she was doing electrical contracting work:

One of my hobbies used to be tropical fish, it was mostly my husband's… I used to give talks over the air on 2FC. I remember going into a restaurant in Bathurst Street. I was doing a job there and I was hammering away at something, and the proprietor came up to me and said, 'Hey missy, will you stop that for a minute.'

So I said, 'Yes, I'm sorry, what's the trouble?' He said, 'I want to listen to the session coming on, on tropical fish.' … And it was [my] session. [14]

In January 1933 [media]the American journal Aquariana published an article written by McKenzie concerning 'Some interesting inhabitants of Sydney seashores', in which she recommended keeping sea horses in a salt-water tank. [15]

The McKenzies had no children of their own, but sometimes took in the two sons of Violet's only sibling, Walter Reginald Wallace, from Melbourne. These boys, Merton Reginald Wallace and Lindsay Gordon Wallace, later operated their own radio shop in Prahran, Melbourne. [16]

Electrocution

Around the corner from the McKenzies in Greenwich lived the Hinks family: Leslie, a businessman with interests in property, engineering and mining, his wife Beatrice and their five children. In late 1934, tragedy befell this family and cast a shadow over the McKenzies' lives too.

Around 6am on Tuesday 27 November 1934, Violet McKenzie stepped outside her house to collect the newspaper from the front garden. She was stopped in her tracks by a shocking sight, as the Sydney Morning Herald reported the following day:

Harold Hinks, 13, of Mitchell-street, Greenwich, was found dead in the garden of Mrs C.R. McKenzie’s house in Green-street [sic], near his home, yesterday morning.

The likely cause of death was apparent:

There was an electric light switch at the gate of Mrs McKenzie’s home to enable the occupants to light up the grounds before passing through them. The police believe that the boy was playing at the gate when he touched a live wire beneath the cap of the switch. The ground was damp at the time, and this fact probably accounted for the severity of the shock. [17]

A coronial enquiry concluded on 10 December that the boy’s death had been accidentally caused through contact with an electrical fitting.[18] The inquest papers have not survived, but newspaper reports offer some detail about the proceedings. The Truth described a report supplied by Government electrical inspectors:

[They] allege that the switch… was installed in 1926, and had become faulty and highly dangerous through wear and exposure to the weather. It is stated there was nothing to reveal the danger associated with the alleged faulty switch to the lay mind, but a skilled electrician in the course of an inspection would have detected any fault immediately.[19]

The Sun, by contrast, reported that the electrical expert at the inquest had found the switch to be in sound condition but was dangerous because it lacked an earth wire:

The switch, explained Inspector Ivor Mitchell of the Electrical Contractors and Licensing Board, controlled a porch light. There was no earth wire connected to the conduit. He himself had received a shock by making contact with the switch and the steps; but apart from the fact that there was no earth wire, the installation was in sound condition.[20]

The Labor Daily reported that Cecil McKenzie spoke at the inquest. He ‘told of how his wife found the lad’s bare feet protruding from under a hedge on wet ground.’ The report continued:

McKenzie said he had never had a shock from the switch and that he had lost a lamp from his porch two months ago. McKenzie declared that Sergt. R.H. Howarth handed him the knob of the switch, which he (McKenzie) said he had found on the ground after the tragedy.[21]

It emerged at the inquest that some months previously the McKenzies had received a complaint from the milkman about the switch.[22] The Truth story included photographs of the exterior of the McKenzies’ house and a marked-up close-up of the gate, captioned ‘The house of tragedy, and the gateway showing the death-dealing switch circled.’ The McKenzies appear not to have been found at fault in the incident. At the conclusion of the inquest, the City Coroner Mr Farrington recommended periodical inspections of electrical installations; a position heartily endorsed by the Truth newspaper.[23]

The tragedy was doubled the day after the electrocution of Harold Hinks. Harold’s father Leslie, aged 42, was in Western Australia on gold-mining business when he received news of his son’s death. In Kalgoorlie, Leslie boarded a mail plane heading east, which took him as far as South Australia. In Ceduna he boarded a Percival Gull single-engine monoplane, specially chartered to carry him back to Sydney in time for his son’s funeral. It was the very same aircraft with which Charles Kingsford Smith had broken the England-Australia record on a solo flight in 1933.[24] This time the plane was piloted by Oliver Blythe ‘Pat’ Hall. It was due to arrive at Mascot airport at 8pm on Wednesday night. But just 100 kilometres short of its destination, the plane crashed into a hillside in wild country near Yerranderie. Hinks was killed. Hall survived with minor injuries.[25]

The following day, Thursday 30 November 1934, a double funeral was held at the Church of St Giles, Greenwich, for father and son. The Sun reported on the funeral that evening:

Many who attended the service this afternoon, at the funeral of the boy, Harold Hinks, who was electrocuted, were unaware that his father, Leslie Hinks, had been killed in a ’plane crash and were shocked to learn that they were present at a double funeral.[26]

About the impact of these tragic events on Florence Violet McKenzie herself, we can only speculate. It is cruelly ironic that a child was fatally electrocuted at the house of Australia’s first female electrical engineer, herself an advocate for and innovator of domestic applications for electricity. That the McKenzies appear not to have been found legally culpable for the accident is a fortunate outcome for them. But the events and the grief of the bereaved Hinks family must surely have weighed heavily upon the McKenzies. The electrocution of Harold Hinks is not something that Violet McKenzie appears ever to have spoken publicly or written about, even when directly addressing the subject of electrical safety.

Taking a long view of her professional trajectory, it appears that the Hinks tragedy roughly coincides with a shift in McKenzie’s vocational focus from entrepreneurial retail work, to voluntary work of an educational nature.

Technical education for women

In the 1930s, Violet McKenzie turned her [media]attention increasingly to teaching other women about electricity and radio. She had observed the need over years of working in the field herself. In 1925, she told the Australian Women's Mirror:

'[T]here are such a lot of women experimenters [amongst my customers] that I would like to form a Women's Wireless Club.' [27]

In 1931 she told a Sunday Sun reporter that she wanted to see a course of lectures on domestic radio and electricity established in girls' schools and technical colleges. [28]

She took matters [media]into her own hands, opening a Women's Radio College on Phillip Street in 1932. She persuaded employers to take on some of her trainees, as one of them later recalled:

During the Depression I joined Mrs Mac's electrical school in Phillip Street. It was the first time girls were involved with electrical circuits, Morse and making radio sets. Later Mrs Mac decided it was time to use our skills in industry, so she persuaded Airzone Ltd to take one of us (me) on trial in their radio section. Soon the others followed from the school, and we started the component parts section, and we were absorbed into many other sections. [29]

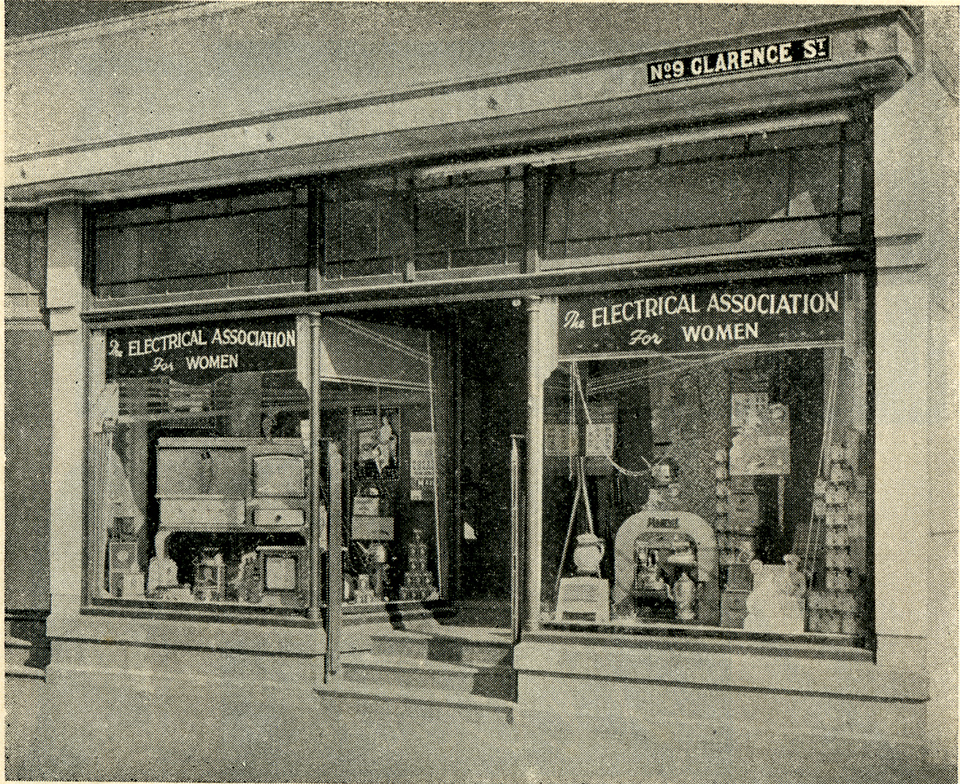

McKenzie [media]believed that electricity could save women from domestic drudgery. She wrote 'To see every woman emancipated from the "heavy" work of the household by the aid of electricity is in itself a worthy object.' [30] To this end she founded the Electrical Association for Women (EAW) on 22 March 1934 at 170 King Street [31], later moving to 9 Clarence Street. The purpose was educational rather than commercial, as a 1936 advertisement for the association makes clear.

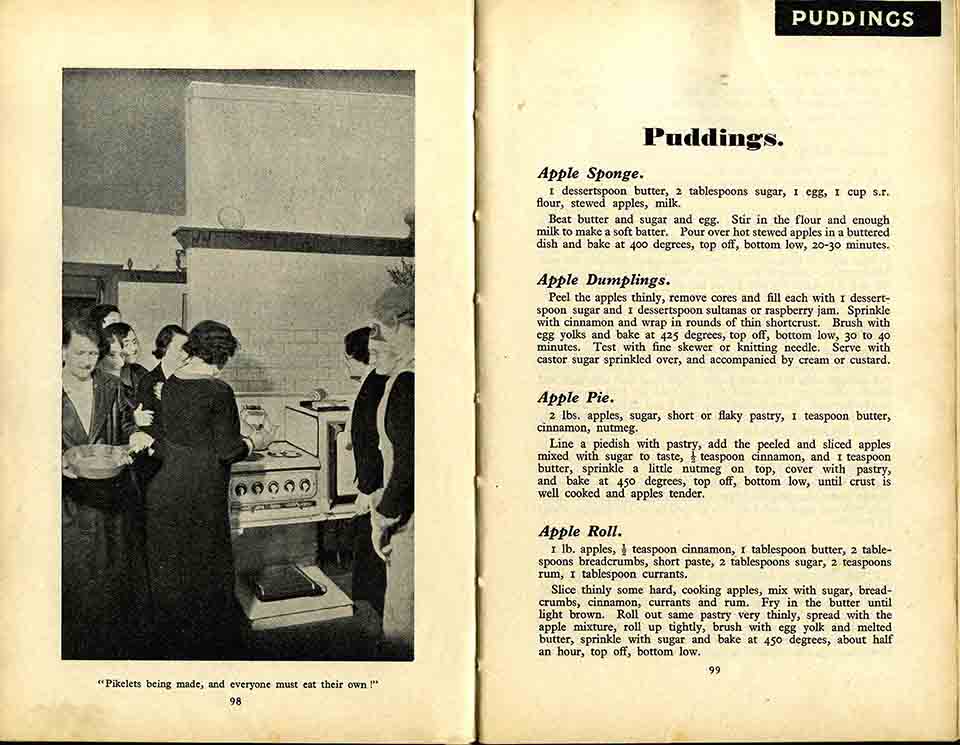

By 1936, McKenzie had [media]sold the Wireless Shop, and was busy at the Electrical Association for Women. She gave electric cooking demonstrations in the EAW kitchen, which was fitted out with show electrical appliances by the Sydney County Council. [32] She compiled the EAW Cookery Book, Australia's first 'all-electric' cookery book, which ran into seven editions and remained in print until 1954.

Electrical safety for children

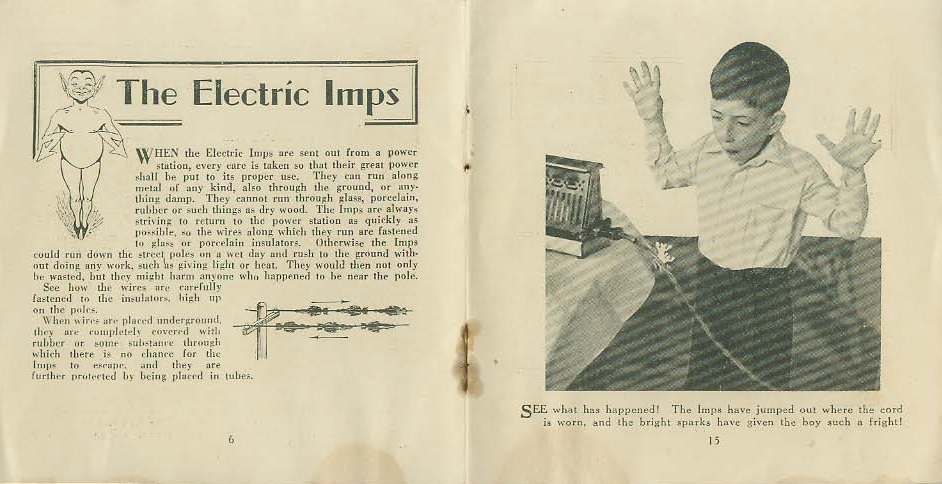

[media]In August 1936, McKenzie was invited by the state government’s Electricity Advisory Committee to join a panel ‘to consider the practicability of preparing suitable literature of an educational nature, preferably illustrated, for circulation throughout the schools in the State’ on the subject of electrical safety. The letter from the Acting Secretary of the committee noted that McKenzie had ‘for some time past been engaged on the preparation of a pamphlet having a similar design and [had] endeavoured to cooperate with the Education Department in this connection.’[33]

In 1937, the Electrical Association for Women published The Electric Imps, a children’s book written and illustrated by its Director, Mrs F.V. McKenzie, and described as presenting ‘The story of electricity, simply told, with the object of educating the youthful mind in its safe use.’[34] Its contents also appeared in the School Magazine and The Sun newspaper.[35]

Wartime initiatives

As World War II [media]loomed, McKenzie saw that with her qualifications and teaching skills she could make a valuable contribution. She foresaw a military demand for people with skills in wireless communications. As she told a reporter in 1978: 'When Neville Chamberlain came back from Munich and said 'Peace in our time', I began preparing for war.' [36]

In July 1938, McKenzie was one of 80 women in attendance at the inaugural meeting of the Australian Women's Flying Corps held at the Feminist Club of New South Wales at 77 King Street. McKenzie was appointed treasurer and instructor in Morse code to the organisation, which was later known as the Australian Women's Flying Club. [37]

In 1939 McKenzie [media]established the Women's Emergency Signalling Corps (WESC) in her Clarence Street rooms. Her original idea was to train women in telegraphy so that they could replace men working in civilian communications, thereby freeing those skilled men up to serve in the war. [38] This she accomplished: by the time war broke out, 120 women had been trained to instructional standard. [39]

But it quickly became apparent that men in the services urgently needed training in wireless communications. A newspaper article in the 1970s described the moment when McKenzie realised that she and her female trainees at the WESC could train servicemen directly:

Early in the war, one young would-be pilot tried to enlist but was refused because he didn't know Morse code…By sheer coincidence he walked past [the Women's Emergency Signalling Corps on Clarence Street] and heard the sounds of Morse signalling.

'It was just a room full of women,' remembered Mrs McKenzie,

'but he walked up to me and said 'Will you teach me Morse code?' I just heaved a big sigh because I saw a whole world opening up in front of me. Then I knew what we could do. We could train girls to train the men. It was wonderful, because I'd thought we could only do things like relieving in the post office.' [40]

[media]Soon the premises at 9 Clarence Street became overcrowded, so McKenzie moved the operation to an old wool store at 10 Clarence Street, where for the next decade the WESC occupied the first and second floors. Sometimes intelligence personnel would appear at the school with complaints from guests in the pub next door, who thought a spy operation was at work when they heard Morse code through the walls each evening. [41]

Some 12,000 [media]servicemen and recruits made their way up the steep wooden stairs for instruction at the bustling WESC school during the war, as McKenzie later recounted:

The Army sent lorry loads of soldiers to have early training in Morse before going to the Middle East, the RAAF sent several groups of servicemen in uniform, with their own instructor... to use our equipment. The Royal Indian Navy sent their Indian communication ratings… Many RAN musterings came to the signalling school to improve their signalling. Scores of American servicemen attended the school, sometimes with their own instructor, but mostly to join our classes. More than forty police officers attended the school in their spare time to reach the necessary standard for enlisting as pilots in the RAAF. [42]

McKenzie ran the school without any government grant or allocation of accommodation by the services. The women of the WESC each gave one shilling per week towards the rent, but no fees were ever charged for tuition: instruction of servicemen was a voluntary effort on the part of McKenzie and the WESC.

To the thousands of men and women who trained at 'Sigs' on Clarence Street, Florence Violet McKenzie was known affectionately as Mrs Mac.

Female telegraphists enter the auxiliary services

McKenzie campaigned energetically [media]to have some of her female trainees accepted into the Air Force and Navy as telegraphists. She encountered a great deal of official resistance. In 1940 she wrote to the Minister of the Navy, WM (Billy) Hughes: 'I would like to offer the services of our Signalling Corps, if not acceptable as telegraphists then at least as instructors.' [43] Her suggestion was dismissed. She travelled to Melbourne to meet with the Naval Board, and invited them to send an officer to test the ability of her trainees.

In early January 1941, Commander Newman, the Navy's Director of Signals and Communications, visited the WESC headquarters on Clarence Street to test McKenzie's trainees. Finding they were highly proficient, he recommended the Navy admit them. [44] Hughes still took some convincing. But the urgent need for trained telegraphists prevailed, and on 21 April a Navy Office letter authorised the entry of women into the Navy. [45] This was the beginning of the Women's Royal Australian Naval Service – the WRANS. The minister's condition was that 'no publicity … be accorded this break with tradition'. [46]

On 28 [media]April 1941, McKenzie accompanied 14 of her WESC trainees to HMAS Harman in Canberra, where they quietly became the first members of the WRANS. The women were dressed in their green WESC uniform which had been designed by their teacher Mrs Mac [47] – it was several months before a female Navy uniform was ready. [48] From this initial intake of 14, the WRANS ranks expanded to some 2,600 by the end of the war, representing about 10 per cent of the entire Royal Australian Naval force at the time. [49]

All told, McKenzie trained about 3,000 women, one-third of whom went into the services. [50] Many others remained at the Clarence Street school as instructors.

In May 1941, the Air Force appointed McKenzie as an honorary flight officer of the Women's Auxiliary Australian Air Force, [51] so she could legitimately instruct Air Force personnel. [52] This was the only official recognition McKenzie received during the war for her efforts.

Postwar wireless training

Violet McKenzie helped with rehabilitation after [media]the war, keeping her school open for as long as there was a need for instruction in wireless signalling. In the postwar years, she trained men from the merchant navy, pilots in commercial aviation, and others needing a signaller's ticket. In 1948, a Sky Script reporter paid a visit to the school and described the scene, and the diversity of students:

At a table in a corner recently there were six elementary trainees: One was a Chinese quartermaster, another a half-Burmese. Two were Americans … One … an aircraft skipper down from New Guinea to get his wireless ticket; and the other chap a ship's officer with the same objective.

In another corner there's an ANA commander preparing for his 20-word-a-minute exam: an English ship's wireless officer … an ex-RAF Wing-Commander … an Indian Navy man… [and] groups of airline 'types' also on the job. [53]

McKenzie told a journalist that, after the war, 'All the airmen came back and wanted to join Qantas, but they needed to build up their Morse speed and learn to use the modern equipment.' [54] The Department of Civil Aviation fitted out a room at the school with transmitters, receivers and radio compass so that pilots could train for their wireless ticket at the school. From 1948, McKenzie held a First Class Flight Radio Telephony Operator License. AR Gray was one of many ex-RAAF airmen who retrained for a civilian career with McKenzie in this period. He wrote:

Being unemployed, we spent almost all of each weekday at the school, so if a tuition fee had been applicable, Mrs Mac would have earned a tidy sum of money. That, of course, was not her way of doing things. She required no payment for the training she provided, and I suspect that she was quite out of pocket over the whole affair…

It would be true to say that a great number of the pilots whose futures were finally fulfilled in airlines in Australia owe a deal to Mrs Mac…

There was no other school operating in Sydney at the time, providing Morse training to potential airline pilots, and no other school then or thereafter giving such training completely free of charge. [55]

Famous aviators who trained for their wireless ticket at McKenzie's school include Patrick Gordon Taylor and Cecil Arthur Butler. McKenzie also trained Merv Wood, later Commissioner of Police in New South Wales, and the principals of the Navigation Schools at both the Melbourne and Sydney Technical Colleges. [56]

Given that Violet McKenzie had no income after she closed her shop in the mid-1930s, running the signal school on a fee-free basis for a decade and a half must have entailed considerable personal sacrifice. Her husband's salary from the Sydney County Council may have been enough to support them both while he was alive. She may have saved money during her time as a retailer. She may have received an inheritance when her parents both died in 1933, though they were of modest means. But McKenzie appears to have made ends meet over long years of voluntary service largely by being frugal and self-sacrificing.

Correspondence with Einstein

In early 1949 McKenzie started writing to Albert Einstein. Her first letter to him wished him a speedy recovery from recent illness. [57] Two of her letters are held in the Einstein archives in Jerusalem. It is clear from the second letter that he wrote back to her at least once. Some accounts claim that McKenzie corresponded regularly with Einstein for as long as 15 years before his death in 1955, [58] but the documentary record suggests such reports exaggerate the extent of the correspondence.

McKenzie herself said that she and Einstein corresponded for some years.

He was very interested in Australia and his favourite daughter, she was really a step-daughter … was terribly fond of shells. And I used to get my marine boys to bring me in shells from the islands, and the air boys, they'd take a big tin of shells over to the States for me.[59]

It's evident from one of her letters that she sent him a boomerang which had been brought to her from Central Australia by an airline pilot. She wrote 'Some of your mathematical friends might like to plot its flight!' [60] There are other reports that she sent him a didgeridoo, and a recording of didgeridoo music when he replied that he couldn't work out how to play the instrument. [61]

Awards and honours

In 1950, McKenzie was awarded an OBE for her wartime services. In 1957 she was elected a Fellow of the Australian Institute of Navigation. In 1964 she became Patron of the Ex-WRANS Association. In 1979 she was made a Member of the Royal Naval Amateur Radio Society. In 1980 a plaque celebrating her 'skills, character and generosity' was unveiled at the Missions to Seamen Mariners' Church, Flying Angel House. [62]

Retirement

According to a People magazine profile of McKenzie written in January 1953, McKenzie received an unceremonious notice from the owners of 10 Clarence Street to quit the premises. The Sands Directory indicates that she moved her operation briefly to No 6 Wharf at Circular Quay in 1953, before retiring to her home at Greenwich Point in 1954.

McKenzie wrote that she closed the school when the airlines established their own school and the government added a signals training section to the Navigation School at the Technical College. She continued to help the occasional pupil with special difficulties at her home. [63]

Final years

Violet McKenzie was [media]nine years older than her husband Cecil, but she outlived him by 23 years. After his death in 1958, she shared her house for a time with Cecil's sister Jean, a primary school teacher. [64]

In May 1977, after a stroke paralysed her right side and confined her to a wheelchair, McKenzie moved to the nearby Glenwood Nursing Home.

She died peacefully in her sleep on 23 May 1982. At her funeral service, held at the Church of St Giles in Greenwich, 24 serving WRANS formed a Guard of Honour. McKenzie was cremated at the Northern Suburbs Crematorium.

The June 1982 [media]edition of the newsletter of the Ex-WRANS Association was devoted to their former teacher and patron. Amongst the memories recorded therein is a statement McKenzie made two days before she died: 'it is finished, and I have proved to them all that women can be as good as, or better than men.' [65]

Notes

This entry was revised by the author in August 2018 to incorporate new information about the electrocution of Harold Hinks in 1934.

[1] Advertisement for The Wireless Shop, The Wireless Weekly, 24 November 1933, p 20

[2] Who's Who in Australia, 1955

[3] Interview with Florence Violet McKenzie at Glenwood Nursing Home, Greenwich, 8 September 1979, by Louise Lansley and Islay Wybenga of the Sydney High Old Girls' Union. Transcript held in the SGHS archives, Moore Park, Sydney

[4] University of Sydney Calendar, 1916, pp 429–30

[5] Interview with Florence Violet McKenzie at Glenwood Nursing Home, Greenwich, 8 September 1979, by Louise Lansley and Islay Wybenga of the Sydney High Old Girls' Union. Transcript held in the SGHS archives, Moore Park, Sydney

[6] Self made success, Sunday Guardian, 20 October 1929

[7] Richard Begbie, 'The Marvellous Mrs Mac, alias FV Wallace – Part 1', Radio Waves Oct 2008, p 7

[8] Interview with Florence Violet McKenzie at Glenwood Nursing Home, Greenwich, 8 September 1979, by Louise Lansley and Islay Wybenga of the Sydney High Old Girls' Union. Transcript held in the SGHS archives, Moore Park, Sydney, p 6

[9] Rosemary Broomham, 'Florence Violet McKenzie', in Heather Radi (ed), 200 Australian Women: A Redress Anthology, Women's Redress Press, Broadway NSW, 1988, p 179

[10] Miss Wallace speaks from 6 KGO, The Australasian Wireless Review, Dec 1924, p 37

[11] FV McKenzie, The Wireless Weekly, 3 April 1931

[12] Marie Dale, 'The Radio Girl 'tunes in' to many interests', The Australian Woman's Mirror, 21 July 1925, p 20

[13] Ex-WRANS Ditty Box, June 1982, p 6

[14] Interview with Florence Violet McKenzie at Glenwood Nursing Home, Greenwich, 8 September 1979, by Louise Lansley and Islay Wybenga of the Sydney High Old Girls' Union. Transcript held in the SGHS archives, Moore Park, Sydney, p 13

[15] Mrs F Violet McKenzie 'Some interesting inhabitants of Sydney Seashores', Aquariana, vol 1, no 7, January 1933, pp 160–1

[16] Conversation with Paul Wallace, McKenzie's grand-nephew, son of Merton Reginald Wallace, February 2008; Sands & McDougall's commercial and general Melbourne directory 1935–55

[17] BOY ELECTROCUTED. Touched Live Wire in Dark, The Sydney Morning Herald, 28 November 1934, p 13

[18] The verdict is recorded in the register of coroners’ inquests: ‘Asphyxia, accidentally caused through coming into contact with an energised conductor of electricity.’ State Records Authority of NSW, Registers of Coroners’ Inquests and Magisterial Inquiries, 1834–1942 (microfilm, NRS 343, rolls 2921–2925, 2225, 2763–2769)

[19] Lives sacrificed to Govt. Lethargy. INSPECT ELECTRICAL INSTALLATIONS! Truth, 9 December 1934, p 14

[20] ELECTRIC PERIL. Coroner Warns, The Sun, 10 December 1934, p 9

[21] SWITCHES SHOULD BE INSPECTED. Coroner’s Remarks On Electrocution At Greenwich, The Labor Daily, 11 December 1934, p 7

[22] SWITCHES SHOULD BE INSPECTED. Coroner’s Remarks On Electrocution At Greenwich, The Labor Daily, 11 December 1934, p 7

[23] ELECTRIC PERIL. Coroner Warns, The Sun, 10 December 1934, p 9; Lives sacrificed to Govt. Lethargy. INSPECT ELECTRICAL INSTALLATIONS!, Truth, 9 December 1934, p 14

[24] The propeller of the plane is part of the collection of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, object number H4997

[25] Father, Dashing To Son’s Funeral, Crashes To His Death, The Sun, 29 November 1934, p 23; TRAGIC SEQUEL TO AIR DISASTER, The Telegraph, 30 November 1934, p 11

[26] Mourners at Double Funeral, in The Sun, 29 November 1934, p 36

[27] Marie Dale, 'The Radio Girl 'tunes in' to many interests', The Australian Woman's Mirror, 21 July 1925, p 20

[28] Careers for girls – Radio offers wide field, Sunday Sun, 1 February 1931

[29] 'DT', 'Other memories of Mrs Mac' in Ex-WRANS Ditty Box, June 1982, p 9

[30] FV McKenzie, 'What have the ladies to say?', The Contactor, 8 November 1935, p 7

[31] Business registration form, The Electrical Association for Women (Australia), signed 3 May 1934 by Florence Violet McKenzie, Electrical Engineer and M.B. Byles, Solicitor, Naval Heritage Collection, RAN Heritage Centre (Spectacle Island Repository), History of the WRANS - various papers

[32] Interview with Florence Violet McKenzie at Glenwood Nursing Home, Greenwich, 8 September 1979, by Louise Lansley and Islay Wybenga of the Sydney High Old Girls' Union. Transcript held in the SGHS archives, Moore Park, Sydney, p 12

[33] Letter from Acting Secretary, Electricity Advisory Committee, NSW Department of Works and Local Government, to Mrs. F.V. McKenzie, 27 August 1936, Naval Heritage Collection, RAN Heritage Centre (Spectacle Island Repository), History of the WRANS - various papers

[34] Florence Violet McKenzie, The Electric Imps: A Story for Children, The Electrical Association for Women 1937

[35] Interview with Florence Violet McKenzie at Glenwood Nursing Home, Greenwich, 8 September 1979, by Louise Lansley and Islay Wybenga of the Sydney High Old Girls' Union. Transcript held in the SGHS archives, Moore Park, Sydney

[36] Greg Flynn, 'Thank you, Mrs Mac', The Australian Women's Weekly, 12 July 1978, p 41

[37] Joyce A Thomson, The WAAAF in Wartime Australia, Melbourne University Press 1991, pp 32–3

[38] Florence Violet McKenzie, 'The Women's Emergency Signalling Corps', Ex-WRANS Ditty Box, April 1976

[39] Norman Ellison, 'Magnificent Mrs Mac!', Sky Script, April 1948, p 14

[40] ''Mrs Mac' – pioneer of the WRANS', newspaper clipping held in the Wrans Naval Women's Association NSW Archives, publication unknown, c1970s

[41] Barbara Small, 'A woman engineer wrote our first electric cook book', The National Times, 26–31 August 1974

[42] Florence Violet McKenzie, 'The Women's Emergency Signalling Corps', Ex-WRANS Ditty Box, April 1976

[43] Cited in Annette Nelson and friends, A History of HMAS Harman and its People, DC-C Publications, Canberra 1993, p 26

[44] Shirley Fenton Huie, Ships Belles: The Story of the Women's Royal Australian Naval Service 1941–1985, The Watermark Press 2000

[45] 1941–1962: WRANS comes of age, Royal Australian Navy News, 24 April 1962, p 1

[46] Cited in Annette Nelson and friends, A History of HMAS Harman and its People, DC-C Publications, Canberra 1993, p 26

[47] Gloria Newton, 'Ex-WRANS plan get-together for 30th anniversary', The Australian Women's Weekly, 10 March 1971, p 15

[48] Annette Nelson and friends, A History of HMAS Harman and its People, DC-C Publications, Canberra 1993, p 26

[49] Margaret Curtis-Otter, W.R.A.N.S.: The Women's Royal Australian Naval Service, The Naval Historical Society of Australia, Garden Island NSW, 1975, p 5

[50] Rosemary Broomham, 'Florence Violet McKenzie', in Heather Radi (ed), 200 Australian Women: A Redress Anthology, Women's Redress Press, Broadway NSW, 1988, p 180

[51] Joyce A Thomson, The WAAAF in Wartime Australia, Melbourne University Press 1991, p 339

[52] To 20,000 men and women she's 'Dear mother – Mrs Mac', Australian Home Journal, July 1963, p 45

[53] Norman Ellison, 'Magnificent Mrs Mac!', Sky Script, April 1948, p 15

[54] 'Mrs Mac is truly special', Reveille, April 1979, p 13

[55] Letter from AR Gray to ex-WRAN Jess Prain, 31 July 1987, held in the Wrans Naval Women's Association NSW Archives

[56] Resume of FV McKenzie's achievements prepared by the Ex-WRANS Association and held in the Wrans Naval Women's Association NSW Archives

[57] Letter from FV McKenzie to Albert Einstein, 7 February 1949, held in the Albert Einstein Archives, Hebrew University of Jerusalem

[58] For example, 'A Dot with a Dash', People, 28 January 1953, p 23

[59] Interview with Florence Violet McKenzie at Glenwood Nursing Home, Greenwich, 8 September 1979, by Louise Lansley and Islay Wybenga of the Sydney High Old Girls' Union. Transcript held in the SGHS archives, Moore Park, Sydney, pp 11–12

[60] Letter from FV McKenzie to Albert Einstein, 28 February 1949, held in the Albert Einstein Archives, Hebrew University of Jerusalem

[61] A Dot with a Dash, People, 28 January 1953, p 23

[62] Flying Angel House has since relocated to 320 Sussex St, where Florence Violet McKenzie's plaque can be found in the garden

[63] Florence Violet McKenzie, 'The Women's Emergency Signalling Corps', Ex-WRANS Ditty Box, April 1976

[64] Conversations with Ex-WRANS Gwenda Cornwallis and Jean Nysen, February 2008

[65] Other memories of Mrs Mac, Ex-WRANS Ditty Box, June 1982, p 11

.