The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Darling Point

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Darling Point

[media]Darling Point is a peninsula suburb on the eastern side of Sydney Harbour, approximately four kilometres from the Sydney central business district bounded by Edgecliff, Rushcutters Bay, Double Bay and Sydney Harbour. [1] Darling Point was first called 'Mrs Darling's Point' in Surveyor Larmer's 1831 field book, in honour of Eliza, wife of the then Governor of New South Wales, Ralph Darling. [2] The name was subsequently shortened to its present form.

First people

The Darling Point area was originally part of the larger territory of the Cadigal clan of the Eora people whose country extended across the southern shores of Sydney Harbour. They lost traditional land and harbour resources after European arrival in 1788 and a smallpox outbreak in 1789 resulted in widespread annihilation with few survivors. Several sources also confirm an Indigenous presence (a 'tribe', and a 'king': Yerinibe or Yaranabi) in the area, well into the nineteenth century. [3]

The Europeans

[media]Steep and heavily wooded terrain, a high ridge and an unstable shoreline delayed European occupation of Darling Point until the 1830s. The construction of a new road in 1831 and Bentley's Bridge over a swampy gully in 1838, improved access slightly. Governor Ralph Darling reserved the land for public purposes having earlier rejected an application for a whaling station. [4] In June 1831, the English Colonial Office introduced a new English crown land policy which effectively abolished the issue of free grants to selected colonial residents. Regulations under the new policy stipulated that all unreleased crown land had to be surveyed, valued and sold at public auction. [5]

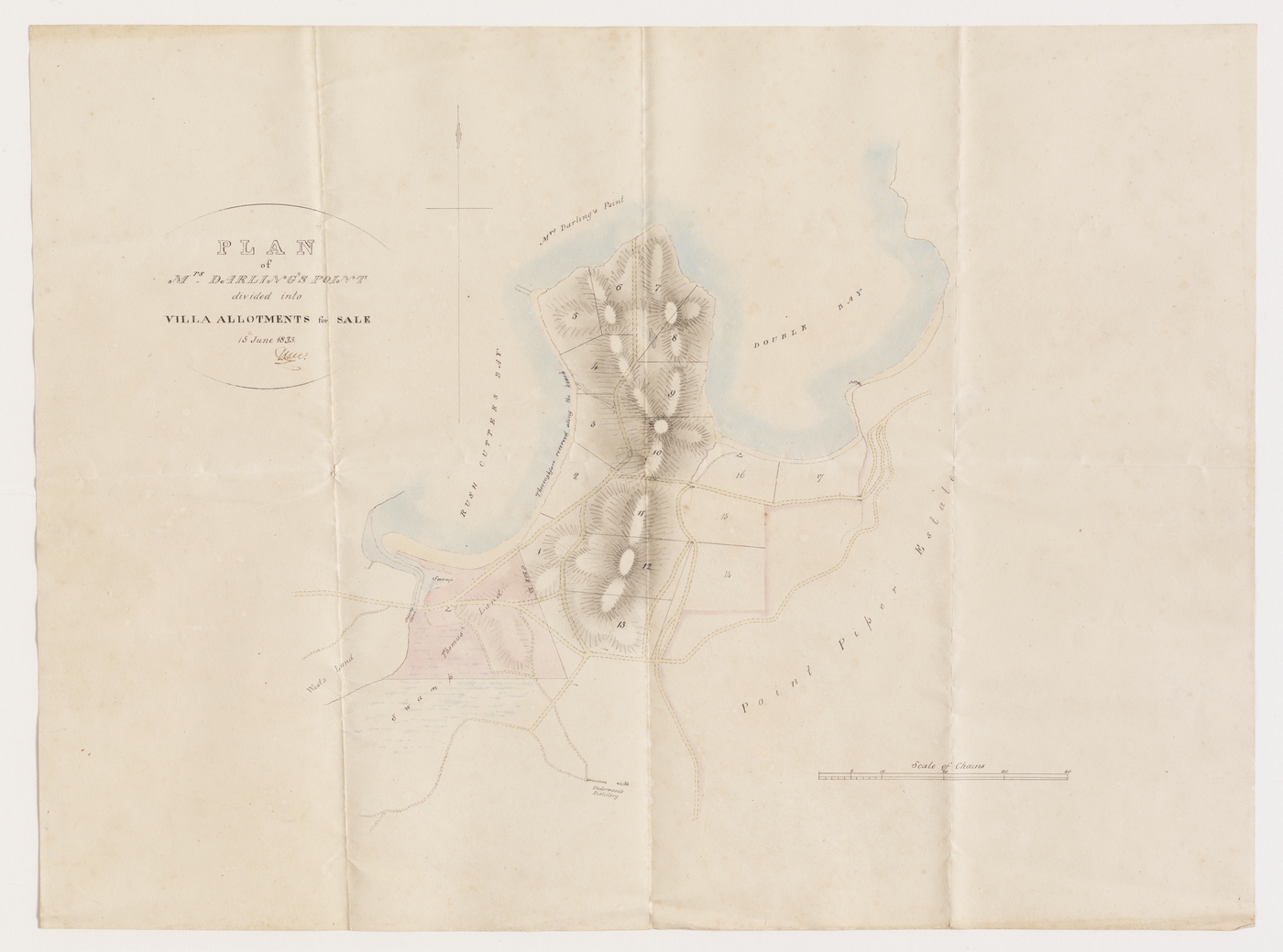

[media]There were delays in the release of Darling Point land for several reasons including disruption caused by a change of governor in late 1831, and (unsuccessful) maneuvering by the Colonial Treasurer Campbell Drummond Riddell to gain special access to a reserved sixteen acres (6.5 hectares). The land in question was ultimately included in the 1833 gazettal of the proposed auction of 'Villa Allotments on Mrs Darling's Point'. [6]

By the early 1830s, acquisition of urban and rural land was a major investment strategy for colonial entrepreneurs and the proposed auction of the Darling Point villa allotments generated a considerable amount of interest. The subdivision prepared by Surveyor Mortimer William Lewis provided thirteen allotments ranging from six to fifteen acres (2.4–6 hectares), together with two government roads (early versions of today's Darling Point and Yarranabbe roads) and an intended road along the western shoreline. [7] When nine allotments were auctioned in October 1833 they realised an average price of £34 per acre (.4 hectare), well above the government's reserve of £10 per acre. The six successful tenderers included retired Third Fleet Private James Chisholm Senior, widowed hotel keeper Elizabeth Pike and four successful businessmen: James Holt, Thomas Barker and the emancipists William MacDonald and Joseph Wyatt.

Holt, Barker and Wyatt each bought two allotments. Thomas Barker purchased another allotment when a further three on the southern end of the peninsula were sold in 1835, increasing his Darling Point land holding to 25.75 acres (10.4 hectares). Successful businessman Thomas Smith bought two allotments comprising 28.5 acres (11.5 hectares) on the south-eastern corner. Another allotment of 15 acres (6 hectares) on the south-western corner was granted to the Colonial Astronomer James Dunlop in 1835, conditional upon the construction of a single dwelling on his land to the value of £1,500. [8]

First developers

The original purchasers of the Darling Point allotments soon disposed of their land, profitably, to a second group of short-term investors. Within six weeks of his October 1833 purchase, James Holt realised a considerable profit on the sale of his 16 acres (6.4 hectares) at the north-eastern end of the peninsula to Colonial Treasurer Riddell who had earlier attempted to gain a free grant for that land. In 1835 Joseph Wyatt sold his two allotments at the north-western end of the peninsula to the Surveyor-General Sir Thomas Mitchell. Both James Chisholm's and Elizabeth Pike's allotments on the eastern side of the peninsula were sold between 1835 and 1837. [9]

By 1845, all of the original allotments had been subdivided into smaller allotments, thus setting the trend for endless subdivisions and re-subdivisions during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It has been suggested elsewhere that Thomas Barker built his large residence, Roslyn Hall, in Darling Point, but this is incorrect. [10] Thomas Smith was the only original purchaser to construct a family residence, Glenrock, in 1836, on his Darling Point land – after he had disposed of a large part of his original holding. In Smith's opinion, Darling Point land 'was becoming too valuable to be idle' [11], a view confirmed by Darling Point's position in the 2011 census as one of the most closely populated suburbs of Sydney at 56.57 persons per hectare. [12]

Reshaping 'Mrs Darling's Point'

During the early 1840s, original Darling Point allotments continued to be subdivided for profit or to deal with the ongoing effects of the serious economic depression. The Lindesay, Mount Adelaide, Delamere and Glenhurst subdivisions provided a large number of new allotments for which new access roads were required. Subsequent Darling Point subdivisions and re-subdivisions were also facilitated by that strategy, resulting in today's myriad of intersecting streets, cul-de-sacs, one-way streets and battleaxe blocks. Very few of the homes constructed on those early subdivisions remain intact but several, which were built on re-subdivisions, now appear in state and local heritage lists.

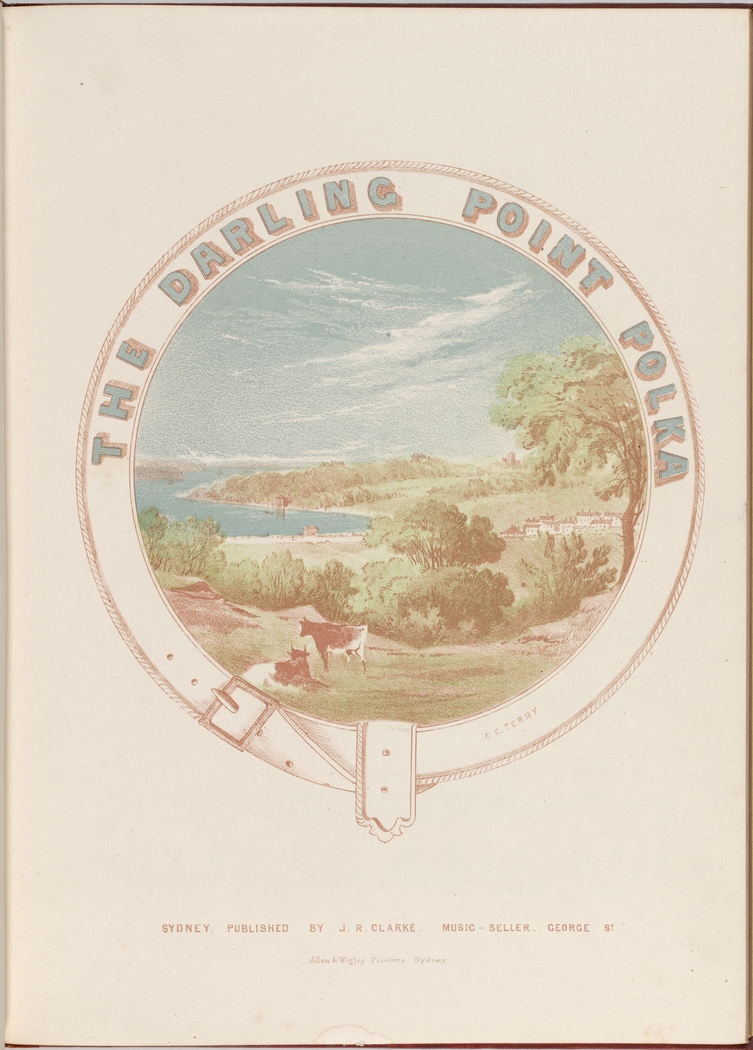

[media]The number of Darling Point residences increased from six in 1841 to 13 at the end of the decade and a permanent close-knit community began to emerge. During the ensuing decades, Darling Point's reputation as a desirable suburb was firmly established by affluent residents who built large villas on their land which they maintained with readily available domestic labour. The owners of those estates enjoyed a high standard of living and several had close familial and business connections. [13] One contemporary journal article described that community as the exclusive 'Darlingpointonians'. [14] Members of the community entertained lavishly in their palatial residences which were the venues for events such as soirees and balls that were so famous that a surviving score from the late nineteenth century was entitled 'The Darling Point Polka'. [15]

Among the new settlers in Darling Point during the 1840s were Thomas Ware Smart MLC and MLA, and Thomas Sutcliffe Mort, who both helped to forge its permanent community. Each played prominent roles in colonial politics, including the campaigns for responsible government and against renewed convict transportation in the late 1840s to early 1850s. [16] Mort was an auctioneer and colonial entrepreneur who made a significant contribution to the emerging Australian pastoral industries with the construction of infrastructure such as Mort's Dock at Balmain, railway rolling stock and the early development of refrigeration for the meat export market. Smart and Mort created large estates where they built their grand villas – Mona and Greenoakes. [17]

A place of worship

[media]As the Darling Point community grew, several residents including Smart, Mort, and Thomas Whistler Smith MLA (son of early settler, Thomas Smith) – known locally as the 'three Toms' – requested Sydney's Church of England Bishop W Broughton to provide them with a place of worship. Broughton agreed to a temporary 'Chapel of Ease' which opened in 1847 in a coach house on Thomas Smart's property, Mona. Mort then donated part of his land for the St Marks Church which was designed by Edmund Blacket and opened on 7 November 1852. During the following decades the 'three Toms' served as trustees and wardens of St Marks and, together with many other generous parishioners, provided considerable financial support for the church. Both Mort and Smart later allowed access through their estates to shorten the parishioners' route to services. [18]

As well as a place of worship, St Marks provided its parishioners with a social centre, and a surviving diary written by Sir Thomas Mitchell's daughter, Blanche, confirms the important role of the church in the lives of those families. Blanche described how her sister and friends sang in the choir, taught Sunday school and joined other parishioners at social gatherings hosted in the parsonage. [19] Two of Blanche's sisters, Alice and Camilla, were married in a double wedding ceremony at St Marks on 16 April 1857. [20] St Marks remains a popular venue for weddings, baptisms and funerals, for its parishioners and the wider community. It is a significant example of nineteenth century Australian ecclesiastical architecture.

Architects and artists

The wealth of many of the original and subsequent residents of Darling Point provided lucrative commissions for skilled architects and designers, including the nineteenth century architects Edward Hallen, Francis Clarke, James Hume, John Bibb, JF Hilly and Mortimer Lewis, as well as Edmund Blacket. Both the villas and local scenery were favourite subjects for colonial artists Conrad Martens and George Peacock, who enjoyed the patronage of the villas' affluent owners. Smart and Mort were avid collectors of artworks which they displayed in specially built galleries in their homes and shared with the public on designated days. Martens also provided art lessons to local women including Mort's first wife, Theresa. Another of his students, Penelope Smith, the mother of Thomas Whistler Smith, was later recognised as an accomplished local sketcher. [21] Family lore also suggests that Martens provided drawing lessons to the well-regarded water colourist Mary Harriet Gedye, wife of Charles T Gedye of Eastbourne, Darling Point. [22] The works of the colonial artists are now treasured by today's public galleries and private collectors as impressive records of Darling Point and its grand nineteenth century villa estates.

Educating the young

Many nineteenth century Darling Point children were either educated overseas, at home by governesses and tutors, or attended fee-paying private schools. Good, free education was not available until late in the century, but during the century's middle years the colonial government provided some financial assistance to approved church schools for teachers' salaries and school supplies. [23] St Marks Church was able to open an elementary parish school in part of Thomas Smart's coach house, where it remained until 1859 when it moved to a site in nearby Edgecliff which was then known as 'St Marks Village'. [24] Secondary education was also provided by the Reverend Henry Cary, a highly qualified Oxford graduate, in his home at St Marks Crescent. His successor, the Reverend George McArthur, also taught boys at the secondary level but moved the secondary section (St Marks Collegiate School) to Macquarie Fields and later resigned his ministry. [25]

The Cooksey Sisters' Young Ladies' Academy was conducted at the Mitchell family's Carthona, and other private schools, were also established during the latter part of the nineteenth century, namely the St Marks Crescent Preparatory Day and Boarding School for boys conducted by the Misses Macaulay, and Mrs Robinson's Preparatory School for boys, Brooksby, in Lower Ocean Street. The non-denominational private girls' school, Ascham, was founded in 1886 by a German woman, Miss Marie Wallis, in a surviving end terrace house at 1 Marathon Avenue. As student numbers increased at Ascham additional educational and residential accommodation was leased in local residences, including Delamere, Queenscliff and Mount Adelaide.

Ascham's next move was to the second Glenrock on the south-eastern corner of Darling Point which was built by John Marks in the late 1870s on the site of Thomas Smith's original Glenrock. The school's new owner and headmaster, Herbert Carter, proceeded to subdivide and sell some of the surrounding land for new home sites. Although Ascham's official geographical address changed to Edgecliff around 1918, it remains the custodian of several of Darling Point's nineteenth and early twentieth century heritage listed residences. [26] Glenrock, Fiona, The Octagon, The Dower House, Yeo-merry (renamed Raine House) and Duntrim House all now form part of the current Ascham school campus.

Mid-century newcomers

After the passage of the New South Wales Constitution Act 1855, and the gradual development of self-government, an increasing number of politicians and members of the judiciary took up residence in Darling Point. The establishment of the elected Woollahra Municipal Council in 1860 and the introduction in 1863 of a reliable new land registration system (Torrens Title) undoubtedly increased the locality's appeal. Several residents owned their own carriages but in 1848 a fairly expensive daily omnibus service was provided between Darling Point and the GPO and it remained the main form of public transport until the end of the century. [27]

During the 1850s, two prominent solicitors – Robert Ebenezer Johnson and James Norton – took up residence respectively in Brooksby and Ecclesbourne, both of which were built on the original Darling Point allotment bounded on the east by Lower Ocean Street which subsequently became part of the suburb of Double Bay. Johnson was an 1856 appointee to the first New South Wales Legislative Council and lived in Brooksby until his death in 1866. [28] Norton was another nominee. He purchased Ecclesbourne in 1857 from the estate of Thomas Whistler Smith and resided there until his death in 1906. [29] Irish-born barrister and politician Edward Butler built his home, St Canice, in the 1860s on part of Thomas Barker's third allotment and lived there until his death in 1879. [30]

The first mayor of the municipal council of Sydney, John Hosking, resided in the mid-nineteenth century Darling Point residence Callooa at 5 Bennett Avenue [31] while the first Woollahra mayor, George Thornton, lived at Longwood on Thornton Street. Judge Alfred Cheeke, the first New South Wales district judge, was listed in the 1860 Woollahra Municipal Council Rate Assessment Record as the owner of allotments on the south-eastern corner of Darling Point which he held until his death in 1876. After Cheeke's death in 1876, his land was purchased by the politician James Watson to enlarge his adjoining Glanworth which had been built in 1863 by Robert Coveny on part of Thomas Smith's original land.

Reclaiming the shoreline

During the late nineteenth century, local residents pressured the colonial government to address the problem of Darling Point's unstable foreshores which posed considerable challenges to landholders. These people included sea captain JC Malcolm whose unsuccessful attempt to build on his foreshore land became known as 'Malcolm's Folly'. [32] After the death of Sir Thomas Mitchell in 1855, his family faced similar problems when marketing the 34 allotments provided in the 1856 Yaranabee [sic] Estate subdivision of his land on the north-western corner of Darling Point. Several of the allotments were located on the unstable shoreline which inhibited sales. Despite this, the retailer Sir William Farmer, with the help of the architect Edmund Blacket, successfully built his home, Claines, in 1865 on his shoreline Yaranabee Estate allotment. In the same year Blacket designed an imposing Italianate mansion, Retford Hall, for another retailer, Anthony Horden II, on several Yaranabee Estate allotments away from the shoreline. [33] Claines was demolished after a 1927 subdivision of the site. Retford Hall remained in the Hordern Family until it was demolished in the early late 1960s.

[media]Local residents, such as the then owner of Lindesay, John Macintosh, urged the colonial government to reclaim the pungent muddy flats around Rushcutters Bay to create parkland. [34] The reclamation was legislated by the Rushcutters Bay Act 1878 and the creation of the Rushcutters Bay Park was undertaken in 1878–79. The completion of the seawall in 1890 further improved the unstable Rushcutters Bay shoreline but landowners continued to be hampered by the inadequate road along its route. Nevertheless, the reclamations facilitated the subdivision of several shoreline allotments and the construction of new homes. In 1902 the Henry Hudson Family was able to sell several Glenhurst residential sites abutting Beach Road. [35] Two surviving late nineteenth century Yarranabbe Road residential buildings – Craigholme [36] and Stratford Hall – were built on large Yaranabee [sic] allotments between Yarranabbe Road and the Rushcutters Bay shoreline.

Late nineteenth century newcomers

During the last two decades of the nineteenth century Darling Point continued to appeal to new residents who built family homes on remnants of previous subdivisions. It remained the preferred address of politicians, members of the legal fraternity and successful businessmen. [37] As well as the surviving heritage listed homes on Darling Point Road, namely Swifts and Cleveland, several other homes were built on remnants of the Delamere subdivision. The solicitor, John Williamson built his new residence, Denholm, circa 1888–89 and the politician and judge, Sir Joseph George Innes, purchased an existing residence, Winslow, on Darling Point Road.

Another member of the Judiciary, the Australian born District Judge, Legislative Councillor and Attorney-General George Bowen Simpson [38] commissioned the architect John Horbury Hunt in 1884, to design his large Victorian Free Gothic style residence, Cloncorrick [39] on remnants of the 1841 Glenhurst Estate subdivision. Although converted into apartments in the twentieth century, Cloncorrick remains on part of its original site at 1 Annandale Street. Horbury Hunt may also have partly designed The Annery, which was built in 1884–86 by the company director and solicitor George Montague Merivale in Marathon Road on the easterly slope of Darling Point at the top of the 'Break Neck Steps' leading to William Street, Double Bay. [40] After Edward Butler's death in 1879, his home at 9–12 Loftus Street, St Canice, was occupied by Sir John Henniker. [41] Butler's home remains on part of its original site, having been used as the Jean Colvin Cancer Care Centre until sold in 2014.

Two other residences, Newstead and Lillianfels, which were built on residues of the Glenhurst Estate have survived into the twenty-first century. The former, a three storey Federation Queen Anne style residence, was built in 1890 and remains at 1 Yarranabbe Road. Lillianfels, an early Victorian Regency town house built circa 1890 (replacing Restormel) remains at 5–9 Yarranabbe Road. [42] During the period, several other responses to changing architectural tastes were built throughout Darling Point, such as the surviving pair of highly decorative duplexes, Lorne-Lindisfarne and Trevenna-Roskear in Darling Point Road. [43]

The 1891 census showed that the number of Darling Point residences had increased to 114 and the population was then 709. However, by the end of the nineteenth century, several owners of large Darling Point estates had died and their families were unable, or unwilling, to maintain their large homes and gardens. Others were adversely affected by the severe economic depression of the 1890s as well as the diminishing availability of the domestic workforce. Subdivisions during the pre-World War I period included Etham, Glenhurst, Mount Adelaide, Mona Estate and Mona Extension, Springfield, Glanworth, Greenoaks, Carthona, Avoca and Lindesay. As well as providing a large number of small allotments, several new access roads were provided for the subdivisions. [44]

During World War I several residents of Darling Point, such as the merchant and politician Sir Alfred Meeks, were actively involved in wartime support organisations. [45] Darling Point residences, such as Stratford Hall on Yarranabbe Road provided accommodation for British and Australian naval personnel who were working at the nearby Sydney Naval Depot. Other Darling Point homes were used by patriotic funds and various charitable organisations to provide extra clothing, foodstuffs and various 'comforts' for Australia's military forces serving overseas. Even after the extremely divisive 1916 and 1917 conscription referenda, the numbers of voluntary war workers in New South Wales involved in that effort remained steady throughout the war. [46]

On 13 August 2014, the Australian Red Cross Society celebrated the centenary of its foundation. Several male and female Darling Point residents had been among the first to join the New South Wales Division and volunteered for several roles. One of the two voluntary joint secretaries of the New South Wales Division's Executive Committee throughout the war was Marjorie Mort, whose family had been closely associated with Darling Point during the nineteenth century.

On 14 August 1914, Darling Point resident Lady Jane Barton, [47] chaired a meeting held at Mrs DC Phipps' home, Disley, in Darling Point Road, which aimed firstly to establish a Darling Point–Double Bay branch of the Australian Red Cross Society and secondly, to form a Darling Point centre for one of the many working circles that emerged during the war. [48] Despite the vehement anti-German atmosphere at the time and his own incarceration, German born brewer Edmund Resch offered space in his large residence, Swifts, for the voluntary war workers. [49] Other private homes in Darling Point, such as The Octagon, were vacated to provide convalescent homes for the returning wounded servicemen. [50]

The inter-war years

The boom in land speculation resumed throughout Sydney after World War I despite the fragile financial condition of the country, a bad drought and the cessation of business during the pneumonic influenza epidemic of 1918–19. [51] By the spring of 1919 economic conditions had improved and Australia entered an era of overly optimistic expansion during the 1920s which included new residential developments. In order to address increasing traffic problems and to reduce the very steep grade near the intersection of Darling Point and New South Head roads, Darling Point Road was widened and divided into two levels in 1925. The heritage-listed concrete balustrade and retaining wall near that intersection were created as part of that project. [52] Darling Point continued to attract prominent new residents such as the barrister Kenneth Street, and his activist wife Jessie, who paid £8,500 in 1927 for a large residence on Greenoaks Avenue. [53] The poet Dorothea Mackellar also chose to make a home in Darling Point during the 1930s when she purchased the late nineteenth century residence, Cintra, which remains at 155 Darling Point Road. [54]

Reflecting the trend to increased residential density in Sydney, 34 buildings of flats were created in Darling Point in the 1920s and another 14 were added by the early 1930s. Some existing homes, such as Kamilaroi on Darling Point Road, were modified for flats. [55] Other large residences were adapted for non-residential purposes, such as the late nineteenth century Denholm on Darling Point Road, which became a private hospital in 1927. Remnants of Denholm are the heritage listed gateposts, the original sandstone retaining walls, balustrade and rock face at Goomerah Crescent. The Stables, at 28 Yarranabbe Road was a 1927 conversion of the Denholm stables. [56]

Depression

During the Great Depression there was no financial support and only limited government sponsored relief work for the thousands of unemployed Australians. One such relief project was the widening of Greenoaks Avenue in 1932 which improved the steeply curving road between Darling Point Road and Ocean Street, Double Bay. [57] In 1931, the plight of the unemployed and their families prompted parishioners of St Marks Church to help needy families in a neighbouring parish. Although many local families were also adversely affected by the economic downturn, by November of that year the Darling Point and Woollahra Relief Fund was regularly supplying several thousand impoverished families with essential food and clothing. [58]

New building construction in Darling Point slowed during the financial crisis but an exception was Craigend, built on a 1927 subdivision of the Claines Estate in 1933–34 by Royal Navy and Royal Australian Navy veteran, Captain James Ronald Patrick. Craigend is a Modernist, International style residence with an architectural blend of Art Deco and Moorish features, designed by the architect Frank Bloomfield. In 1938, a roof-top dome and second floor rear wing were added. The home became the residence of the United States Consul from 1948 to 1999 after which it passed into private hands.

World War II

During World War II, the Sydney Naval Depot at Rushcutters Bay was used as a recruitment and training centre for naval personnel including the Women's Royal Australian Navy (WRAN). It was also the site of the Anti-Submarine School which opened in 1939 to provide anti-submarine training for Australia and its allies. [59] Accommodation was provided for both RAN and WRAN personnel in Darling Point homes, such as Stratford Hall, Ranelagh, Hopewood House and The Octagon. By the end of the war, the RAN Recruiting Office nearby in Loftus Street had processed 6,000 recruits. [60]

Once again Darling Point volunteers provided assistance for Australia's Defence forces. The Woollahra–Darling Point branch of the Australian Red Cross Society sold fresh vegetables, homemade jams and pickles at local stalls to finance food and clothing parcels for Australian servicemen and women and English air-raid victims. [61] The Darling Point Active Service Comforts Fund met on Mondays and Fridays in Mrs Whiteman's house at 51 Darling Point Road to make camouflage netting. [62] In January 1945, the fund committee donated £768 and sixteen shillings towards the provision of a first aid room in the Hyde Park British Centre. [63] Other Darling Point residents made other contributions such as providing working space in their homes. For example, Mr and Mrs Resch provided the Woollahra Civilian Aid Service with space for a rest centre in the ballroom of their home, Swifts. [64] There was even an attempt to encourage local housewives to undertake voluntary work by establishing a locally owned 'Co-operative Home Delivery Service' to reduce their household shopping commitments. [65]

Post-war years

A serious shortage of residential accommodation in the post-World War II years in Sydney was caused by factors such as the cessation of residential construction during the war, shortage of building materials and the restrictive effect of the Landlord and Tenant Acts 1941 which discouraged investment in rental properties. [66] The severity of the housing shortage was illustrated by the direct action taken in July 1947 by three ex-servicemen and their families who, in desperation, illegally occupied Greenoaks Cottage in Darling Point. [67]

The accommodation crisis prompted various responses including the amendment to the early residential building statutes. The concept of co-operative ownership of multi-occupancy residential buildings (later known as Company Title) had been accepted since the 1920s when buildings such as the Astor at 123 Macquarie Street, Sydney, were developed and sold under that structure. [68] That form of ownership of multi-occupancy buildings continued until the late 1950s and early 1960s when Woollahra Municipal Council began to approve subdivision plans of developers who found Darling Point a rich source of suitable properties. As a result, several remaining large nineteenth century homes were demolished and replaced by multi-storey buildings. The first example of the new style of building was Glenhurst Gardens which replaced the attractive 1870s Victorian mansion Glenhurst in 1959–60. The design by the architect D Forsyth Evans provided 100 home units of varying sizes and four levels of garage spaces. Their title was represented by shareholdings in the holding company, Glenhurst Gardens Limited. Although later, Darling Point buildings were much higher and bulkier and several were insensitively built on the northern harbour end of the peninsula, the perceived excessive height and bulk of the Glenhurst Gardens provoked a considerable amount of criticism. [69]

Despite that criticism, the demolition of Darling Point's nineteenth century residential heritage continued. In fact, it greatly increased after the passage of the New South Wales Convey ancing (Strata Titles) Act 1961, which provided individual title to apartments as compared to the ownership of shares in a company title structure. By the end of the 1960s, two Hordern family homes were demolished and replaced by multi-storey apartment buildings which were then known as 'home unit buildings'. Prior to the introduction of strata title, Woollahra Council attempted to preserve some of the land for park use but approval was given in 1959 for the subdivision of the Retford Hall property at the corner of Yarranabbe Road and Thornton Street into four allotments, and for the conversion of the residence into apartments. In fact, only the name of the original residence has survived on its replacement multi-storey apartment building. Similarly, Lebbeus Hordern's 1918 Art Nouveau style Hopewood House at 13–15 Thornton Street was also replaced in 1966 by another multi-storey apartment building, Hopewood Gardens. [70]

Strong public criticism of excessively high building projects prompted Woollahra Municipal Council to seek planning advice from town planners Clarke, Gazzard and Partners who provided a development plan in 1970. By 1971 a detailed residential building code was introduced which was intended to enforce strict building conditions. [71] Prior to the introduction of that code, Woollahra Municipal Council attempted to maintain the residential character of Darling Point by introducing strict zoning conditions.[72] Even prior to the enactment of the new code, Woollahra Municipal Council refused to grant the Sisters of Charity permission to replace Sir Samuel Hordern's Babworth with a new St Vincent's Private Hospital. [73] After legal challenges, Woollahra Municipal Council agreed to the subdivision of some of the land and the use of the residence as a convalescent care facility. In 1965 approval for a small shop on part of the original Babworth Estate on the corner of Mitchell and Darling Point roads was granted to a unit holder of the Babworth Gardens apartment building. [74] That shop evolved into Ricky's Café and Convenience.

New government regulations in 1979 for convalescent homes led to the conversion of Babworth House for reuse as a hospice and later nurses' quarters. In 1999 it was sold to developers, the Byrne Lewis Group, who restored the house, converted it into five apartments and added new separate dwellings to the site in 2001. [75]

Architectural heritage

In 1979 the Burra Charter was enacted [76] and in 1979 the New South Wales Heritage Act 1977 was amended to incorporate conservation provisions in the local government planning procedures under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act of 1979 . Since that time there has been a growing local appreciation of Darling Point's residential heritage illustrated by the formation of the Darling Point Society which plays an effective advocacy role whenever local heritage and other community issues arise.

Although there are few remaining large development opportunities in Darling Point, developers continue to 'redevelop' whenever appropriate sites become available. Despite the challenges posed by developers, there have been some attempts to preserve what remains of the suburb's residential heritage and to protect its natural environment, for example, the threatened eighty-year-old trees in Yarranabbe Park. Although Darling Point's skyline is now dominated by high-rise buildings, remnants of its nineteenth and twentieth century residential history have survived, some of which are now listed in state and local heritage schedules. While only four residences have statutory protection as state heritage listed properties – Bishopscourt, Babworth House, Lindesay and Swifts [77] – over 115 items are included in Schedule 3 of Woollahra Municipal Council's 1995 Local Environment Plan. [78] That schedule includes not only surviving buildings, but also trees, gardens, stone retaining walls, gateposts, streetscapes, bus shelters and sandstone features, all of which provide traces of Darling Point's European history.

Two heritage-listed gateposts at the corner of Darling Point Road and Carthona Avenue bear the names of Lindesay and Carthona, two early nineteenth century residences in Carthona Avenue, and two early twentieth century residences, Neidpath and Beach Manor. Various heritage studies have referred to illustrations in English architectural pattern books which influenced Australian colonial house design, such as JC Loudon's 1833 Encyclopaedia of Cottage, Farm and Villa Architecture and Furniture and Francis Goodwin's Rural Architecture 1835. Both Lindesay and Carthona incorporated various domestic Gothic Revival design features which were popular in the early and mid-nineteenth century period. Both have been categorized as 'Old Colonial Gothic Picturesque' residences.

Lindesay and Carthona now share James Holt's original land with residences of varying architectural styles within one of Sydney's most prestigious residential precincts. Substantial early twentieth century homes were built on that land, including Neidpath and Beach Manor on Carthona Avenue and Homeworth and Youbri on Lindsay Avenue, all of which commanded spectacular views. Youbri (renamed Glanworth) was built circa 1915–16 in the North American Ante-Bellum style for an American resident. A later resident was Samuel Henry Ervin, a major supporter of the National Trust. Glanworth remains in private hands. [79] Homeworth was built in the inter-war period by George Wirth, a founder of Wirth's Circus. Wirth's home was replaced in 1954 by a palatial, modern 'Marine Villa' successfully marketed in 2013 for a reputed sale price in excess of $50 million.

A most desirable twenty-first century address

The vision of local residents such as John Macintosh ensured that Darling Point evolved into today's comparatively leafy suburb with its attractive tree-lined streets, parks and reserves. As well as Rushcutters Bay, Yarranabbe and McKell Parks, two small reserves provide tranquil areas for harbour viewing. These are the Darling Point Reserve at the northern harbour end of Darling Point Road (which was a favourite haunt of local infants and their carers during the 1920s) [80] and the Loftus Reserve at the corner of Mona and Loftus roads. The Darling Point Reserve, established as road reserve in 1838 as part of a drainage reserve, was landscaped in June 1984 and upgraded in 1996. [81]

Since the release in 1833 of 'Mrs Darling's Villa Allotments', Darling Point's built environment has changed considerably, as has its demographic. Most of the grand nineteenth century mansions and large gardens have been replaced by multi-occupancy apartment buildings. Only 176 (7.1%) single family homes remain in Darling Point and the vast majority of Darling Point's 3,812 residents live in high density (81.1%) or medium density (11.7%) residences. A significant proportion (38.7%) of residents live in lone person households and their age structures vary considerable, with 27.5% of residents falling within the older age grouping (65 plus) [82]. Despite its increasing density, Darling Point continues to attract well-educated and affluent residents. [83] It remains predominantly a residential suburb whose residents share its parks and waterways with visitors throughout the year, particularly for yachting events and New Year's Eve fireworks displays.

Further reading

Broomham, Rosemary. Darling Point Thematic History, Street Patterns and Subdivision. Woollahra: Woollahra Municipal Council, 2000.

Spearritt, Peter. Sydney since the Twenties. Hale and Ironmonger, Sydney, 1978.

Whitaker, Anne-Maree. 'Darling Point: The Mayfair of Australia.' MA Thesis, University of Sydney, 1983.

Withycombe, SMW. Honourable Engagement: St Marks Church Darling Point: The First 150 Years. St Marks Anglican Church, Darling Point, 2002.

New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage, State Heritage Register.

Notes

[1] Woollahra Municipal Council Community Profile, 1, http://profile.id.com.au/woollahra, Web ID =110, viewed 22 October 2012

[2] Archives Office of New South Wales Series 2/4996, quoted in Anne-Maree Whitaker, 'Darling Point: The Mayfair of Australia' (MA Thesis, University of Sydney, 1983), 1

[3] Grace Karskens, The Colony. A History of Early Sydney (Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin, 2009), 37, 16; David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales from its first settlement in January 1788 to August 1801, second edition (London: Printed by T Cadell and W Davies in the Strand, 1804), 39; Newspaper Cuttings, 24 January, 1903, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, vol 114, 28 quoted in Keith Smith, 'Aboriginal life around Port Jackson after 1822', Dictionary of Sydney, 2011, www.dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/aboriginal-life-around-port-jackson-after-1822, viewed 29 May 2012; Richard Hill and George Thornton, Notes on the Aborigines of New South Wales: with personal reminiscences of the tribes [sic] formerly living in the neighbourhood of Sydney and the surrounding districts (Sydney: Government Printer, 1892), 7, quoted in Keith Smith, 'Aboriginal life around Port Jackson after 1822', Dictionary of Sydney, 2011, www.dictionaryof sydney.org/entry/aboriginal-life-around-port-jackson-after-1822, viewed 29 May 2012

[4] James Jervis, The History of Woollahra: A Record of Events from 1788 to 1960 and a Centenary of Local Government (Sydney: Municipal Council of Woollahra, 1961), 36; Anne-Maree Whitaker, 'Darling Point: The Mayfair of Australia' (MA Thesis, University of Sydney, 1983), 3

[5] Brian Fletcher, Colonial Australia before 1850 (Melbourne: Thomas Nelson Australia, 1976), 84, 85; NSW Government Gazette, no 69, 26 June 1831, 239

[6] Governor's Despatches, Archives Office of New South Wales, A1207, quoted in Anne-Maree Whitaker, 'Darling Point: The Mayfair of Australia' (MA Thesis, University of Sydney, 1983), 3, 4; New South Wales Government Gazette no 69, 26 June 1833; Anne-Maree Whitaker, 'Darling Point: The Mayfair of Australia' (MA Thesis, University of Sydney, 1983), 4, 5

[7] New South Wales Department of Lands, copy of original subdivision plan, S1– 820, prepared by Surveyor M Lewis, 9 October 1833

[8] Anne-Maree Whitaker, 'Darling Point: The Mayfair of Australia' (MA Thesis, University of Sydney, 1983, 9–12; similar conditions were attached to Governor Darling's earlier grants, circa 1828 of the Woolloomooloo Heights (Darlinghurst) Villas

[9] Anne-Maree Whitaker, 'Darling Point: The Mayfair of Australia' (MA Thesis, University of Sydney, 1983), 20, 21

[10] In fact, Roslyn Hall was built on the other side of Rushcutters Bay in today's Darlinghurst. See Alison Vincent, 'Barker, Thomas,' Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/AO10055b.htm, viewed 29 March 2011 and Julia Horne and Geoffrey Sherrington, 'The Gift of Education' in Sydney Alumni Magazine (March 2012): 24, 25, an extract from Sydney: The Making of a Public University (Sydney University Press, 2012). See James Broadbent, The Australian Colonial House. Architecture and Society in New South Wales 1788–1842 (NSW: Hordern House, Sydney in association with the Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales and supported by the Friends of the Historic Houses Trust), 187, 214–15

[11] Nesta G Griffiths, Some Houses and People of New South Wales (Sydney: Ure Smith 1949), 120

[12] Woollahra Municipal Council Community Profile, 1, http://profile.id.com.au/woollahra, viewed 22 October 2012

[13] One lynch-pin was the late Commissary General, James Laidley, whose two daughters married two brothers, Thomas and Henry Mort, Anne-Maree Whitaker, Darling Point: The Mayfair of Australia (MA Thesis, University of Sydney, 1983, 1) 25

[14] 'Sydney and its Suburbs,' The Month: A Literary and Critical Journal (August 1857): 99, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (MJ 4 Q 11) Available online http://library.sl.nsw.gov.au/record=b1029735~S1, viewed 4 February 2016

[15] 'The Darling Point Polka' in The Australian Musical Album for 1863, Sydney: JR Clarke, 1863 (Sydney : Allan & Wigley), Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (DSM/Q786.4/C) available online http://library.sl.nsw.gov.au/record=b2012287~S2, viewed 2 February 2016

[16] Peter Cochrane, Colonial Ambition: Foundations of Australian Democracy (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2006), 247, 253–55, 337–38

[17] Mort preferred this spelling of the name of his residence.

[18] SMW Withycombe, Honourable Engagement: St Marks Church Darling Point: The First 150 Years (Sydney: St Marks Anglican Church, Darling Point, 2002), 6–11

[19] Blanche Mitchell, Blanche Mitchell Diary 1858–61, volume 11, 27 January 1858, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, MSS 1611

[20] Horace William Alexander Barder, 'Wherein Thine Honour Dwells: The story of one hundred years of St Marks Parish Church, Darling Point, NSW (Sydney: HWA Barder, 1948),123

[21] 'Mary Harriet Gedye b. 1834' Design and Art Australia Online, https://www.daao.org.au/bio/mary-harriet-gedye/, viewed 2 February 2016

[22] 'Mary Harriet Gedye b. 1834' Design and Art Australia Online, https://www.daao.org.au/bio/mary-harriet-gedye/, viewed 2 February 2016

[23] This system was later abolished by Henry Parkes' Public Instruction Act 1880 which abolished State aid for denominational schools.

[24] SMW Withycombe, Honourable Engagement: St Marks Church Darling Point: The First 150 Years (Sydney: St Marks Anglican Church, Darling Point, 2002), 20, 21. The school later became the private Edgecliff Preparatory School which later was moved to its present site at Sydney Grammar School.

[25] That school later became part of The King's School, Parramatta.

[26] SMW Withycombe, Honourable Engagement: St Marks Church Darling Point: The First 150 Years (Sydney: St Marks Anglican Church, Darling Point, 2002), 61–2, 85–6, 115,129, 156. See also Caroline Fairfax Simpson, Annette Fielding-Jones Dupree and Betty Winn Ferguson (eds), Ascham Remembered, 1886–1986 (Sydney: Ure Smith, 1986)

[27] The omnibus service between 8 am and 10 am and 2 pm and 5 pm, returning to Darling Point half an hour later each time. See Rosemary Broomham, Thematic History of Darling Point (Woollahra: Woollahra Municipal Council, 2000), 10

[28] Martha Rutledge, 'Johnson, Robert Ebenezer (1812–1866)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://www.adb.anu.edu.au/biography/johnson-robert-ebenezer-3862, viewed 5 November 2014

[29] Allars, KG, 'Norton, James (1824-1906)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/norton-james-4310, viewed 13 June 2016

[30] Bede Nairn, 'Butler, Edward (1823–1879),' Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A030291b.htm, viewed 30 March 2011

[31] 'Callooa – House,' Gardens, New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage, State Heritage Register, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetailS.aspx?ID-2, viewed 6 September 2014

[32] During the late nineteenth century and the twentieth century, further reclamations and drastic re-contouring of the difficult shoreline of Malcolm's site provided suitable sites, firstly, for several substantial homes which, in turn, made way for the large, high rise apartment buildings, such as Yarranabbe Gardens, which were built on subdivisions of that site during the 1960s to1980s.

[33] Joan Kerr, Our Great Victorian Architect, Edmund Thomas Blacket (1817–1883) (NSW: The National Trust of Australia), 66–67

[34] The Sydney Morning Herald, 7 July 1911, 6, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article 15250-56, viewed 30 March 2011

[35] Today's New Beach Road. Rosemary Broomham, Darling Point Thematic History, Street Patterns and Subdivision (Woollahra: Woollahra Municipal Council, 2000), 4, 5

[36] Victorian rustic gothic style house, built for JF Want circa 1897–98, 'House (55 Yarranabbe Road, Darling Point),' New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage, State Heritage Register, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=2710180, viewed 6 September 2014; Joan Kerr, Our Great Victorian Architect, Edmund Blacket (1817–1883) (NSW: The National Trust of Australia, January 1983), 67

[37] Of the 40 members of the 1877–78 Legislative Council, 18 were Eastern Suburbs residents, including six from Darling Point. Quoted in Anne-Maree Whitaker, 'Darling Point: The Mayfair of Australia' (MA Thesis, University of Sydney, 1983), 65

[38] JM Bennett, Simpson, 'Sir George Bowen (1838–1915),' Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A060143b.htm, viewed 27 April 2011

[39] 'Freeland, JM, Hunt, John Horbury (1838–1904),' Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.biography/hunt-john-horbury-3822/text6063, viewed 30 August 2011

[40] 'Annery, The – Residential,' New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage, State Heritage Register, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=2710081, viewed 27 February 2014. It has been suggested that stones from a convict era guard house on the site were used in the construction of the house.

[41] Anne-MareeWhitaker, 'Darling Point: The Mayfair of Australia' (MA Thesis, University of Sydney, 1983), 62, 63, 64

[42] 'Former House and Grounds (Lillianfels),' New South Wales Office of Environment, State Heritage Register, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx, viewed 1 July 2013

[43] 'Lindisfarne,' New South Wales Office of Environment, State Heritage Register, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=2710051, viewed 1 October 2013

[44] Rosemary Broomham, Darling Point Thematic History, Street Patterns and Subdivision (Woollahra: Woollahra Municipal Council, 2000), 35

[45] 'Martha Rutledge, Meeks, Sir Alfred William (1849–1932),' Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/meeks-sir-alfred-william-7549/text13171, viewed 30 August 2011

[46] Australian Red Cross (NSW) Division, Annual Report (1915–16): 30 and (1919): 43–123

[47] The Bartons moved to 'Avenel', Darling Point in 1909. 'Jane Barton,' Australia's Prime Ministers, Your Story, Our History, National Archives of Australia, http://primeministers.naa.gov.au/primeministers/barton/spouse.aspx, viewed 9 November 2011

[48] 'Meeting at Darling Point,' The Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 15 August 1914, 1

[49] The Sydney Morning Herald, 28 September 1942, 4, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article/17804451/, viewed 30 March 2011

[50] Minutes of Meeting of the Executive Committee of the Australian Branch of the British Red Cross Society, New South Wales Division, 2 July 1916

[51] Peter Spearritt, Sydney Since the Twenties (Sydney: Hale and Iremonger, 1978), 46

[52] 'Concrete Balustrade,' New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage, State Heritage Register, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=2710210, viewed 2 February 2016

[53] Peter Sekuless, Jessie Street: A Rewarding but Unrewarded Life (St Lucia, Qld: University of Queensland Press, 1978), 16

[54] Eric Russell, Woollahra: A History In Pictures (Sydney: John Ferguson Pty Ltd in Association with Woollahra Municipal Council, 1980), 105

[55] Rosemary Broomham, Darling Point Thematic History, Street Patterns and Subdivision (Woollahra: Woollahra Municipal Council, 2000), 8

[56] Woollahra Municipal Council, Building Application 393/20, Woollahra Local History Centre

[57] 'Darling Point Trees – Cut Down for Road Widening', The Sydney Morning Herald, 15 December 1932, 10, http://nla.gov.au/nla.new-article 17834376, viewed 30 March 2011

[58] SMW Withycombe, Honourable Engagement: St Marks Church Darling Point: The First 150 Years (Sydney: St Marks Church, Darling Point 2002) 139,140

[59] The Sydney Morning Herald, 10 February 1939, 3 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article\12095780, viewed 30 March 2011

[60] The Sydney Morning Herald 26 April 1947, 16, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article\18023416, viewed 30 March 2011

[61] The Sydney Morning Herald, 17 September 1940, 4 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article/17700644, viewed 30 March 2011 and 13 February, 1941, 14 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article/107290/, viewed 30 March 2011

[62] The Sydney Morning Herald, Photo 22 August 1940, 16, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article 26 February 1942 3 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article/17738416/, viewed 30 March 2011

[63] The Sydney Morning Herald, 26 January 1945 4 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article/17942840, viewed 30 March 2011

[64] The Sydney Morning Herald, 28 September 19424 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article/17804451, viewed 30 March 2011

[65] A group of local ladies (including Jessie Street) attempted to form a local co-operative delivery service to 'time-manage' their household commitments. The Sydney Morning Herald, Wednesday 30 December 1942, 5, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article, viewed 30 March 2011

[66] Peter Spearritt, Sydney Since the Twenties (Sydney: Hale and Iremonger, 1978), 82, 83, 105, 106

[67] The Sydney Morning Herald, Wednesday 8 July 1947, 3, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article18023416, viewed 30 March 2011

[68] Jan Roberts, The Astor (Avalon Beach, Sydney: Ruskin Rowe Press 2003): 7–10

[69] Rosemary Broomham, Darling Point Thematic History, Street Patterns and Subdivision (Woollahra: Woollahra Municipal Council, 2000), 10. See also Caroline Butler-Bowdon and Charles Pickett, 'Inner-city apartments 1950–80,' Homes in the Sky: Apartment Living in Australia (Sydney: The Miegunyah Press in association with the Historic Houses Trust, 2007),107

[70] Prior to its demolition Hopewood House was converted in 1950 by the Sisters of St Joseph of California for use as a finishing school/female accommodation renamed Rosary Villa, The Sydney Morning Herald, 16 November 1950, 80

[71] Peter Spearritt, Sydney Since the Twenties (Sydney: Hale and Ironmonger, 1978) 109, 110

[72] After the introduction of the new code, as well as new commercial businesses, including private hotels (such as Glen Ascham in Sutherland Crescent) were prohibited; 'Local History Fast Facts – G,' Woollahra Municipial Council Library, http://www.woollahra.nsw.gov.au/library/local_history/local_history_fast_facts, viewed 2 February 2016

[73] A grateful patient, Major Harold de Val Rubin, purchased and gifted the Babworth House property to the Sisters for a new private hospital.

[74] Woollahra Municipal Council, Building Application 509/65, Woollahra Library, Local History Centre, Building Applications: Babworth Gardens

[75] 'Babworth House,' New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage, State Heritage Register, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=5044995, viewed 2 February 2016

[76] The Burra Charter was the Australian adaptation of the 1966 Venice Charter by the International Council on Monuments and Sites. 'Guidelines to the Burra Charter: Cultural Significance,' as reproduced in Peter Marquis-Kyle and Meredith Walker, The Illustrated Burra Charter: Making Good Decisions About the Care of Important Places (Australian Heritage Commission in association with Australia/ICOMOS, 1992), 73

[77] Babworth House, Bishopscourt, Lindesay and Swifts are all listed on the State Heritage Register of the New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage.

[78] Woollahra Local Environment Plan 1995 (Amendment No 67), as amended 10 June 2011, Schedule 3 Heritage Items, Woollahra.

[79] 'House, Grounds, Gardens (5 Lindsay Avenue, Darling Point),' New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage, State Heritage Register, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=2710075, viewed 2 February 2016

[80] Jill Buckland, 'Growing up in Darling Point' in A Taste of Woollahra: A Tasteful Anthology of Life in Australia's Oldest Suburb, edited by Robin Brampton (Darlinghurst: A Media House Production, 1987), 52–63

[81] McKell Park and Darling Point Reserve Plan of Management, Executive Summary, Woollahra Municipal Council, Department of Primary Industries; Catchments and Lands, 1 August 2012, 1

[82] The 2011 census revealed that 61.3% of residents hold tertiary qualifications 21–23 and 39.1% earn more than $1,500 per week, 40–43; see 'Darling Point: Population, dwellings and ethnicity,' Community Profile, profile.id, http://profile.id.com.au/woollahra/population?WebID=110, viewed 2 February 2016

[83] Educational and income statistics for Darling Point in the 2011 census reveal that 61.3% of residents hold tertiary qualifications 21–23 and 39.1% earn more than $1,500 per week, see 'Darling Point: Population, dwellings and ethnicity,' Community Profile, profile.id, http://profile.id.com.au/woollahra/population?WebID=110, viewed 2 February 2016